This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

One night in 2016, Laura Modi was facing an acute episode of an eternal parenting problem: trying to get your infant to eat. Modi had just given birth to her first child, a girl, and she was attempting to breastfeed, in part because she wanted to and in part because the American Academy of Pediatrics encouraged it. But Modi was struggling to produce milk and dealing with mastitis, a painful breast-tissue inflammation that can lead to infection — just two of the many medical, professional, and societal obstacles that can make breastfeeding impossible. Like three out of four new parents, Modi was going to have to use formula to keep her infant fed.

As Modi paced the aisle of a pharmacy in San Francisco, where she worked as Airbnb’s director of hospitality, the decision didn’t feel so simple. She was fighting off a fever, her daughter was screaming, and she couldn’t kick the feeling that she had somehow failed. The cans on the shelf didn’t look like the kinds of products that parents like Modi — millennial, coastal, Whole Foods shoppers — were used to buying. The formula was packaged in primary colors and had a list of multisyllabic ingredients on the back: cholecalciferol, cyanocobalamin. And some of them used corn syrup? Forget about it. Feeding her child a can full of powdered ingredients she would never buy for herself felt like a betrayal. In the harsh fluorescent glare of a late-night drugstore aisle, Modi came face-to-face with the emotion that dominates much of 21st-century parenting: the feeling that no matter how much you are doing for your baby, it is never enough. Modi says she was so embarrassed by the can of Similac she bought that she hid it in the back of her cabinet.

Luckily for Modi, she was struck by two other powerful feelings: “a mother’s intuition that there had to be a better option” and a disruptor’s nose for an opportunity. Her comrades elsewhere were already optimizing breast pumps and outfitting bassinets with “smart technology.” They had even invented Soylent, a formula for adult babies.

But no one had touched the $4 billion domestic market for infant formula, which had been dominated for decades by just three large corporations. “We know science has evolved; we know consumer taste has evolved. So why is it that I’m buying the same boomer brands that existed 40, 50 years ago?” Modi told me recently, after recounting her well-worn founder origin story. “Infant formula is one of the last remaining industries where we haven’t seen some level of disruption. That was appealing.”

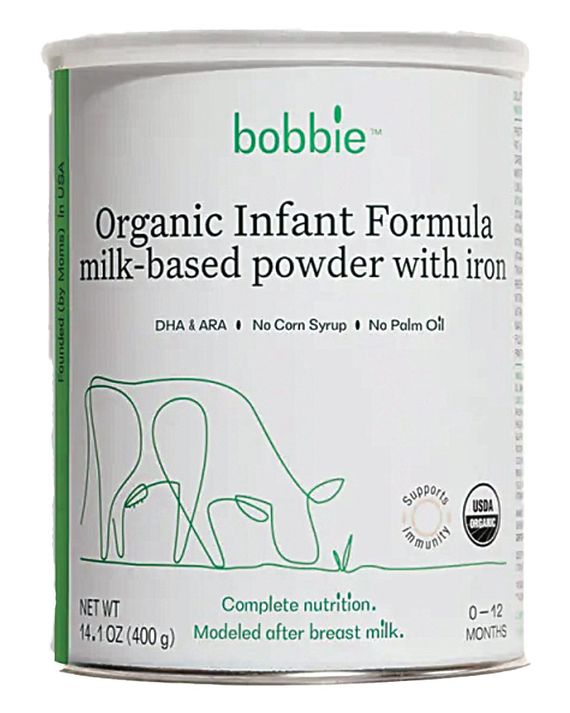

In 2018, Modi left Airbnb to start Bobbie, named after the word her daughter used for her bottle. Bobbie promised American parents something they couldn’t find at CVS or Target: a “European style” formula, closer in recipe to what mamans and Mütter were serving in Lyon and Berlin. It cost more than three times as much as standard American formulas but came with organic milk and the trappings we’ve come to expect from hip direct-to-consumer brands: a package delivered to your door with a soothing Key-lime-green font and printed with an image of Bobbie’s bovine mascot, Moonique, who is meant to represent all the grass-fed cows who produce the formula inside. Modi says she “wanted to create a formula that wouldn’t leave me with even more mom guilt,” and Bobbie was calibrated to help millennial parents — today’s primary childbearing demographic — feel less stressed about one of the countless choices they have to make. She closed a $2.4 million seed-funding round a week before giving birth to her second child.

Bobbie launched three years later, in 2021. It only took a year for Moonique to become a critical component of America’s supply chain. In February 2022, following the deaths of two infants seemingly from a bacterial infection from contaminated baby formula, an Abbott Laboratories plant in Sturgis, Michigan, that makes its Similac formula was shut down after the Food and Drug Administration launched an investigation. (No concrete link has been established between the infections and formula produced by Abbott; Abbott announced a voluntary recall on February 17.) The plant produced a fifth of all formula in the U.S., and neither the industry nor the government seemed to have a plan for what to do. By May, many retail shelves were empty. Desperate parents resorted to driving from store to store for hours, deploying internet shopping bots, serving dangerously watered-down bottles, and cooking up homemade formulas with recipes that dated from the Eisenhower administration. At least two children were hospitalized as a result of the shortage.

Modi is careful not to talk about the shortage as a business opportunity — but that’s what it was. She had hoped to disrupt an industry, then the industry had disrupted itself. New parents are reluctant to switch infant-formula brands so long as their babies aren’t spitting it up, but the shortage gave some of them no choice: An expensive formula looked like a good deal as long as it could get to your door. Within a week of the Sturgis shutdown, Bobbie’s sales doubled; eventually, the company was so overwhelmed with orders that it had to stop taking new customers. By August, it had scored a spot on the shelf in Target stores nationwide, right alongside the cans Modi had once objected to.

Formula supplies remain low in parts of the country with Abbott announcing last week that the Sturgis plant would finally start producing Similac again. But the crisis has started to recede, opening room for questions about the future of an industry revealed to be broken — and who will profit. Bobbie isn’t alone in having good timing. In March, just weeks after the recall, Ron Belldegrun and Mia Funt, two siblings in Manhattan, launched another direct-to-consumer formula company called ByHeart that promised its own special recipe. ByHeart’s sales exceeded projections by 15 times, and it too had to stop taking new customers. Both companies have collectively raised more than $250 million in venture capital on the notion that nearly 3 million American infants are formula-fed every year, and that capturing the kind of parents wooed by Moonique and organic ingredients — and willing to spend any amount to give their child every perceived advantage — could be wildly lucrative.

A critical reading of ByHeart and Bobbie is that they are Goopified versions of cheaper formulas that already exist, and which are every bit as nutritious — that they are catering to consumer preferences, rather than pediatric ones, and preying on the “mom guilt” Modi promised to alleviate. A different interpretation, which Bobbie and ByHeart are promoting, is that they are transformational businesses in the classic start-up mode, breaking into an industry that has grown complacent. “I got into this to reform this industry,” Modi told me multiple times. When I spoke to the founders of ByHeart, they seemed genuine but also used variations of the word innovate more times than any start-up founder I’ve ever met — and I once spent half an hour with Adam Neumann. Both companies launched into a crisis and pitched themselves as heroes. They promised to deliver American parents from their latest insecurity — at least so long as they didn’t create a new one.

The quirks of the baby-formula industry that made room for ByHeart and Bobbie — and led to the shortage this year — have been brewing since the 1950s. The postwar baby boom introduced new customers, and developments in formula-making brought convenience that outweighed the cost. Similac (“similar to lactation”) came to market in 1951, followed a few years later by Enfamil (“infant meal,” if you squint). They remain the predominant formulas today. Younger mothers were especially quick to adopt a product that promised scientifically calibrated benefits as well as liberation from the tyranny of breastfeeding. The early 1970s saw the lowest rates of breast-feeding in decades — only 6 percent of infants were being breastfed six months after birth — and in 1980, a researcher in New York City’s Bureau of Maternity Services said that, for some women, the ability to feed your child formula was “a kind of status symbol.”

But the industry had also come into disrepute. Nestlé and other companies were using salespeople dressed as nurses to push formula in developing countries, where parents sometimes unknowingly overdiluted their formula or mixed it with contaminated water. Breastfeeding rates started to rise again, and, in 1980, Congress passed the Infant Formula Act, which set nutritional and safety requirements managed by the FDA. “This is much more like producing a drug than a food,” says Belldegrun, the CEO of ByHeart, who started the company after spending eight years at a health-care-focused hedge fund. The regulations brought welcome standards and reassurance for parents but also made breaking into the market even more difficult. Since 1980, Abbott and Mead Johnson, which makes Enfamil, have controlled more than 80 percent of the market.

That consolidation was cemented by the federal government’s Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children — WIC, for short — a crucial program that provides nutritional support for lower-income families. WIC has always encouraged breastfeeding, but it also covers the cost of formula. During the 1980s, formula prices increased by more than 150 percent, vastly outpacing the price of milk. In response, President George H.W. Bush mandated that each state run a competitive process in which the lowest bidder would win an exclusive contract to sell formula to WIC families. (The program is federally funded but administered separately by each state.) The system limited choices for lower-income families but worked as a cost-cutting measure. States now pay as little as 15 percent of the retail price, saving taxpayers more than a billion dollars every year. The large players that dominate the industry — since the mid-’90s, every WIC contract in all 50 states has gone to Abbott, Mead Johnson, or Nestlé — are willing to make this deal not only because the program accounts for more than half of all baby formula sold in the U.S. but also because retailers are more likely to stock the WIC-approved formula, which can then be sold to other consumers at retail prices. When California switched its contract from Similac to Enfamil in 2007, Enfamil’s share of the state’s market grew from 5 to 95 percent.

Modi encountered the industry’s barriers to entry right away. In 2019, she and her co-founder, Sarah Hardy — Modi’s “work wife” from Airbnb — launched a trial with 100 families in San Francisco, offering a “companion” formula for toddlers. But confusion about its marketing, and whether it could be safely served to an infant, got the attention of the FDA, and Bobbie voluntarily recalled its product. When Bobbie relaunched in 2021, its formula was made by Perrigo, a white-label manufacturer that helps new brands get to market by creating recipes that don’t run afoul of FDA rules.

The powdery contents of baby formula are one of the many mysteries that greet new parents. So what is it? The primary ingredient in most formula is milk, most often from a cow and typically skim. The milk is mixed in a giant vat with a protein called whey; a sugar, usually lactose, which serves as a necessary carbohydrate for growth; and several different vegetable oils — sunflower, safflower, rapeseed, soybean — that provide babies with the fatty acids they need to grow. Sprinkle in some vitamins and minerals meant to approximate some of the contents of breastmilk, and maybe toss in a prebiotic, then run the mix through a spray dryer to turn it into a powder. Mix with water, and serve. There are different recipes for babies born prematurely, or who suffer from particular allergies, but most pediatricians agree that as long as your baby is drinking the stuff, there is little functional difference between most formulas on the market.

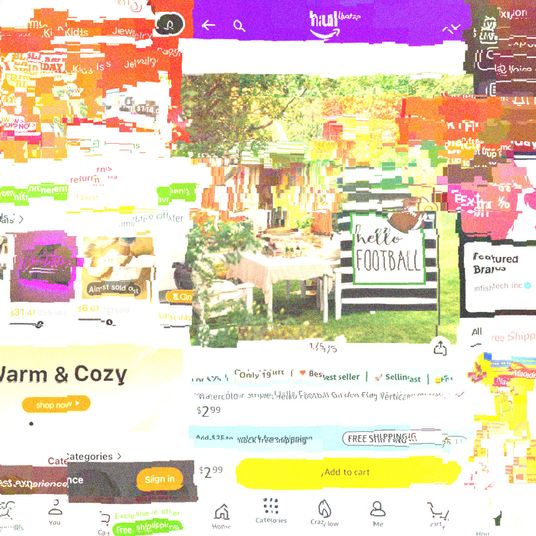

But this is modern parenting, which means the situation could not be so straightforward. In the formula world, there are now countless websites that scrutinize the variable nutrient levels of every product. Abbott alone produces a dozen versions of powdered Similac, including several designed “for fussiness and gas.” Lisa Richardson, a pediatric dietitian who runs the site Formula Sense, told me that many of these were “solutions in search of a problem.”

The aesthetic and ethical preferences of millennials have followed them into parenthood. Instead of Pampers, there are Jessica Alba’s plant-based diapers printed with avocados and sweet potatoes; instead of Desitin, you can buy Kristen Bell’s diaper-rash cream, packaged in millennial pink; and if Gerber doesn’t feel good enough, Jennifer Garner sells squeezable pouches of organic baby goo. (The old-school brands, including the formula giants, now have organic versions, too.) A tech company called Hatch Baby — no relation to the bougie maternitywear brand of the same name — makes a diaper-changing pad that doubles as a scale, allowing nervous parents to keep track of their baby’s weight after every feeding rather than waiting for their next pediatrician’s visit. If there is something for a parent to fret about, there is likely a product promising to ease their mind.

Modi’s decision to position Bobbie as a European-style formula was driven by a market demand: Many parents in her cohort had suddenly begun taking the drastic step of importing formula from Europe. A study from 2018, the year Bobbie launched, found that 20 percent of formula-feeding parents at a New York City pediatrician were importing formula from Europe. (The demographic most likely to do this: white moms with college degrees and household incomes greater than $200,000.) Only 8 percent had received any guidance about European formulas from their doctor, but the survey respondents said they had become convinced that imported formula was the healthier choice for their babies. In short: Brest was best. “I remember being on Park Slope Parents” — a notoriously hyperactive online forum — “and people would post at the beginning of summer, ‘Is anyone going to Europe? I will pay you whatever you want to smuggle formula back for me in a suitcase,’ ” one parent of two children who are safely beyond formula-drinking age told me. Bobbie sells cans measured by the gram — the European way — and the company’s Instagram profile advertises the brand as “Organic Infant Formula for your bébé.”

There are differences between American and European formulas both in what regulators require and in what they prohibit. (Europe, in general, has stricter regulations about the use of pesticides.) But there is no scientific evidence that European formulas are safer or more nutritious than American ones. While Modi had been concerned about all the scary-looking words on the formula cans, they were there because FDA regulations require listing scientific ingredient names, such as cholecalciferol and cyanocobalamin; European companies can use their common names, vitamins D and B12. Many parents blanch at the inclusion of corn syrup in some American formulas, but it’s not the high-fructose kind and is only used in formulas for babies who can’t tolerate lactose. In a post on Formula Sense, Richardson gave a rating of “three dirty diapers” to the claim that European formulas “are more like breastmilk,” noting that both “have extremely similar nutrient profiles.”

But consumers wanted it, and having formula delivered by an American company rather than imported through the black market was appealing. When ByHeart launched this year, it did so without the explicit European connection, focusing on the fact that it is the only U.S. formula that uses whole milk, rather than skim, which some pediatricians believe is a promising innovation. ByHeart conducted a clinical trial — 100 babies on its formula, 100 breastfed babies, and 100 babies on Enfamil — in which the authors found that ByHeart’s babies spat up less than the Enfamil kids and showed “more efficient growth.” Bobbie and ByHeart have inevitably been compared to each other, and many pediatricians are glad to have new products pushing the established players in the market. But if you’re going to pay more than three times the cost of Wirecutter’s pediatrician-approved recommendation — a Costco generic, also produced by Perrigo — how to choose? Do you like the idea of ByHeart’s whole milk or Bobbie’s two extra milligrams of DHA, a fatty acid that studies suggest is critical for brain function? And before you make any final decisions, are you really okay giving your child a formula without taurine, a nutrient found in breastmilk that studies show may or may not be beneficial to your kid? Neither ByHeart nor Bobbie have any.

Both start-ups insist that the stuff inside their cans is what attracts parents. “People come to us for a simple reason: ‘Baby eats it, baby doesn’t spit it up, and baby shits it out well,’ ” Kim Gebbia Chappell, Bobbie’s vice-president of marketing, told me. But they have both put effort into making parents feel good about the choice they’re making. Modi has spoken about Bobbie as a product that should “spark joy,” as if she were selling The Life-Changing Magic of Not Spitting Up. Each can of Bobbie is printed with a quirky sticker — MILK DRUNK IN LOVE, BOTTLE SERVICE — and the company’s website features a diverse set of parents. ByHeart’s chief brand officer previously worked for J.Crew and Hatch, the Alex Mill of maternitywear, and has published a book on modern French couture. Both companies market their products as gluten free, even though virtually every formula is gluten free by default. “We did the work on everything from what’s in the formula to social — everybody else had overlooked this, and it’s the stuff that matters to millennial parents,” Chappell said. “We normalized what it means that you are unboxing your formula on Instagram — Reeves, this did not happen before Bobbie.”

In June, President Biden held a roundtable with formula-company executives to discuss long-term solutions to the shortage. The government had followed the lead of Park Slope Parents and was now flying formula in from Europe, but the 60 million bottles arriving from the Netherlands, Switzerland, Germany, England, and Australia were a temporary salve: They amounted to a week’s supply. While Abbott was notably absent at the roundtable, Belldegrun had scored an invite. ByHeart’s launch just weeks after the Sturgis shutdown had been fortuitous and hectic. “My wife and I just had our second this past weekend,” Belldegrun told the group.

“Good luck with the new babe, ol’ buddy,” Biden said.

ByHeart had scored a seat, rather than Bobbie, because the company had taken a different path to market. Instead of going through Perrigo, the white-label manufacturer Modi had used, Belldegrun and Funt decided to create a recipe from scratch that would have to go through a clinical trial to get approved, and to buy a factory of their own. The facility in Reading, Pennsylvania, is the first new formula plant approved by the FDA in 15 years. This had been costly — ByHeart has raised nearly three times as much money as Bobbie — but when the shortage hit, the company was better able to position itself as a potential solution. Belldegrun told Biden that his company was waiting on approval from the FDA to open two additional facilities and that ByHeart believed it was on a path to feed 500,000 babies — more than 10 percent of American infants, enough to challenge Nestlé for third place. Belldegrun told me ByHeart expected to hit that target within two years and had even more ambitious goals. “We didn’t go buying factories, and conducting clinical trials, and raising $190 million to be a one-product company,” he said. “We built this to be a nationally accessible brand.” He suggested that ByHeart would be expanding into specialized recipes and “showing up as a feeding partner throughout the nourishment continuum from pregnancy through toddler.”

When Modi and I spoke in August, six months after the recall, she said that Bobbie still had “tens of thousands of people” on its waiting list. She wanted to increase production, but doing so would take months. Bobbie had even asked its “suite of influencers” to stop posting about the product. In a time of genuine crisis, the classic start-up playbook — virality, growth at all costs, breaking things — simply didn’t work. “For us to increase production, we need to invest in manufacturing,” she said. “That will take years, not months.”

Neither start-up is in a position to solve the formula crisis, but they are both interested in shaping the industry’s future. Modi had moved to Washington, D.C., mostly to be a few time zones closer to her family in Ireland, but she admitted that “it doesn’t hurt” being close to the policymakers who will play a large role in determining her company’s future. In September, the White House is hosting a conference on health and nutrition — the first in more than 50 years — and Politico recently reported that this summer saw a “mini lobbying boom” around the formula industry. Bobbie and ByHeart both hired lobbyists, and the major players were devoting additional resources to courting lawmakers. (Even Amazon has gotten involved: WIC sales currently have to take place in a store, but Amazon is hoping the crisis might push the government to allow them online.) One possibility is giving WIC families more choice about which formulas they can buy; an Ohio Republican has introduced the Improving Newborn Formula Access for a Nutritious Tomorrow Act — yes, it spells INFANT — to that effect.

The FDA also announced that it was considering allowing European imports permanently. Both Bobbie and ByHeart support this in the short term, but a lasting shift would put them in a bind. Modi has long argued that European formulas were special and that its domestic imitation of them was the crucial advantage Bobbie offered to parents. Now, she was arguing that we should be wary of anything crossing the Atlantic. “The moment we take a temporary solution and apply it permanently raises a lot of questions,” she said, asking how the FDA would guarantee safety and manage recalls from abroad. She cautioned against “a ‘made in China’ situation.” Christina Berberich, Bobbie’s head of regulatory and safety issues, who previously worked at Abbott, echoed Modi’s concerns. But when I asked Berberich whether European formula had a history of safety issues or recalls worse than the U.S., she couldn’t point to anything in particular.

As an alternative, both Modi and Belldegrun said they hoped the government would support more domestic manufacturers. Modi said that could be Bobbie’s future, and with all of the market disruption this year, other competitors will almost certainly emerge. Several start-ups, here and abroad, have spent the past few years trying to develop a formula derived from breastmilk stem cells. Max Rye, the co-founder of a company called TurtleTree Labs, has said its attempt to create infant formula is merely a test case for a more ambitious goal: “to replace all milk.”

So what’s a dedicated, caring, and confused parent to do? The FDA has proved itself unworthy of our blind faith, as has the biggest company in the industry — but the past decade of blitzscaling start-ups hasn’t necessarily given us reason to put a critical food source in the hands of people new to the business. The theoretical arrival of stem-cell breastmilk isn’t likely to make the choice any clearer.

Modi often talks about her company as a “cultural movement,” as start-up founders tend to do. Her particular mission, she says, is to fight the stigma that forced her to shamefully hide her formula can in her pantry, and to put formula feeding on equal footing with breastfeeding. When Bobbie launched its first major marketing campaign last year, it intentionally did so in August — National Breastfeeding Month. “Did we poke a few bears? Yes,” Chappell told me. “But we like to say that we are radically centrist.”

This is a favorite Bobbie catchphrase, meant to position the company between Big Bottle — the makers of Abbott and Similac — and “what we call ‘lactivists,’ ” as Chappell put it. Breastfeeding rates in America have gone up and down over the years, driven by medical discoveries, activism, and political and societal choices. (Some studies have shown higher rates of breastfeeding in countries with paid parental leave.) Neither ByHeart nor Bobbie would argue their formula is more nutritious than breastfeeding — a ByHeart ad: “Breast is best. We’re next” — and both the medical Establishment and those skeptical of it recommend breastfeeding whenever possible. But the exact benefits are unclear. It’s difficult to separate breastfeeding from other factors, and clinical trials are hard to design: No ethical researcher is going to blindly assign different feeding practices to new parents in a maternity ward.

The American Academy of Pediatrics didn’t necessarily help matters this summer, when it released its first updated guidance on breastfeeding in a decade. The AAP renewed its recommendation that infants breastfeed exclusively for six months — but it encouraged parents to continue doing so for a full two years. Many exhausted mothers threw their breast pumps across the room. The AAP said its goal wasn’t to stigmatize parents who use formula but rather, in fact, to fight a different stigma, against parents who choose to breastfeed their children. In 2021, the journal Maternal & Child Nutrition published a paper titled “Guilt, Shame, and Postpartum Infant Feeding Outcomes: A Systematic Review.” The paper found that whether parents choose to breastfeed or give their infant formula — well, pretty much all of them feel like failures.

The pandemic years have taught us a lot about the difficulty of public-health messaging, but it’s still depressing to see the system fail on a topic as fundamental to the species as feeding infants. Modern parenting has become a buffet of choices with no perfect option and a battle against stigmas on every flank. Bobbie’s mission to destigmatize formula feeding even risked creating a negative perception of its own: that parents who can’t afford its formula weren’t giving their kid the same chance as parents they saw posting about Moonique on Instagram. “Are we creating second-class-nutrition citizens?” Richardson, who runs Formula Sense, asked me. “The most innovative formula from ten years ago — that’s what the WIC kids get.”

Modi was aware of that danger. “ This probably is the biggest thing that keeps me up at night,” she said. “This is not a situation where Kind Bar can say something critical about Clif Bar. Shame on any formula company or brand for positioning another formula in a bad light.” The right answer to all of this was to support parents no matter what choice they made. Doing so would require meaningful parental-leave policies, boosting the funding for the WIC program, better guidance and more understanding from health-care providers, and generally relieving parents of the anxious feeling that their best isn’t enough. But where’s the profit in that? Modi was still in pitch mode when I asked her about this, insisting there was “room to uplevel” the standard for formula in the U.S. But she also offered a message to parents that would have been comforting to her younger self: “If you feed your baby Similac, like I did with my first child, your baby is going to be perfect.”