On January 23, Anna Wintour was in Paris, taking in the Armani Privé couture show from the front row at the Palais de Tokyo. Meanwhile, back at the ranch in lower Manhattan, her staff at Condé Nast had broken into open revolt, picketing on the West Side Highway outside the company’s headquarters at One World Trade. A series of union members riled up the crowd. “Be brave, be courageous, do some wild shit, because right now, those suits upstairs are at their meeting table, snickering about how all of you are weak,” said one. “Is that true, are you weak?” “Nooooo!” the crowd bellowed back.

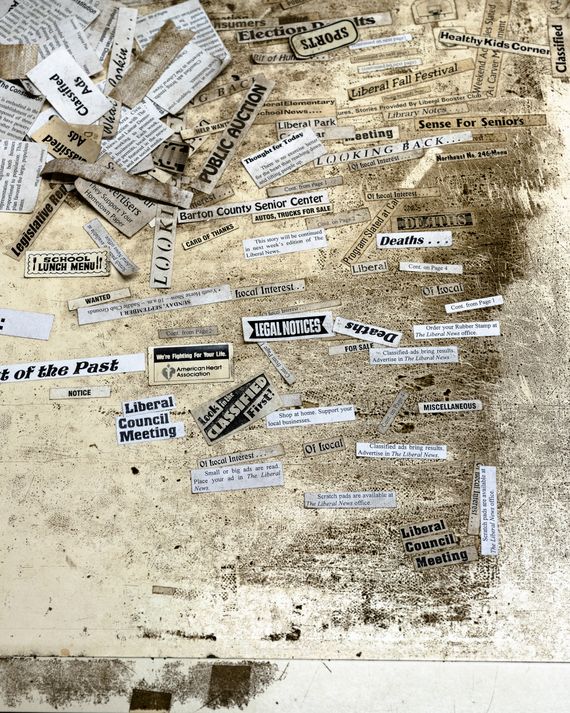

It is an especially miserable time to be employed there — and nearly everywhere else in media. Lately it has felt like much of the media industry has been put through a trash compactor: Time magazine had layoffs, and Sports Illustrated was essentially euthanized. The day of the Condé strike, the L.A. Times axed more than 20 percent of its newsroom; two days after the strike, Business Insider announced it was laying off 8 percent of its staff. The Washington Post just bought out 240 employees. It has dawned on journalists that journalism might all but cease to exist in the near future — and that whatever form it takes is being shaped by executives who have no clear idea how to create a sustainable business.

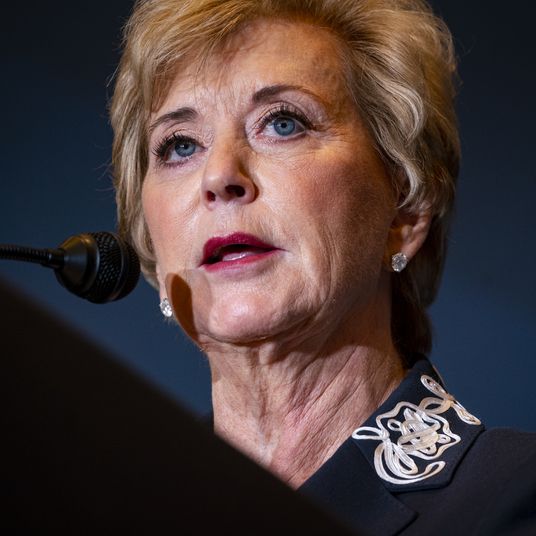

Condé’s unionized staff has been bargaining for a new contract with management, and a list began to circulate in November with the names of 94 employees who will be shown the door once the contract is signed (labor law prohibits canning employees during negotiations). Those people are expected to work until the moment they aren’t employed, and no one knows when that might be. The previous week, Wintour had informed staff that Pitchfork was being folded into GQ; word soon spread that she didn’t bother to remove her signature sunglasses as she told them this news, which didn’t exactly soften the blow. (Although as one person at Vogue pointed out to me, she wears these prescription sunglasses at almost every meeting.) Enough was enough: Some 400 employees stopped working for 24 hours, smack in the middle of Paris Fashion Week and on the day Oscar nominations were announced.

Alma Avalle, a 25-year-old writer and web producer at Bon Appétit who wore a “Free Palestine” patch, delivered a philippic against the C-suite. But when I asked what she thought about Wintour’s stewardship in particular, Avalle grew nervous: “Ummmm, no comment.” I finally found one brave Teen Vogue employee willing to go there. She gave her name and title and said it was time for Wintour to clear out. A few hours later, a panicked union representative emailed me to say the Teen Vogue employee “was feeling extremely nervous about being quoted as saying what she said (particularly about Anna). As you can imagine there is still a lot of fear about repercussions, when it comes to Anna. Would you mind making her quote anonymous?” The union rep added that “my secret goal at conde nast is to get workers confident enough to say FUCK ANNA WINTOUR on the record lol.”

That remains some “wild shit” no one seems quite ready to do. Annaconda still inspires fear — and respect. Were it not for her relationships with the luxury advertisers Condé still very much depends on, the company would be in even worse shape. It’s a different story when it comes to CEO Roger Lynch. The employees were more than happy to trash him on the record. “We’ve been pushing to speak with Roger Lynch since bargaining began,” Avalle explained. “We’ve marched on his offices. We’ve gotten no response.” There is a long-percolating panic inside One World Trade that perhaps Lynch has no master plan to keep the business afloat besides trimming editorial budgets.

In becoming a target, Lynch is not alone. Increasingly, journalists have moved on from ascribing blame for the collapse of the news business to “the internet” and vast technological forces beyond their control. They’re blaming corporate executives who seem unable to come up with plans that cobble together revenues from subscriptions, dwindling advertising money, e-commerce sales, and events — which is what successful executives have accomplished at the New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and elsewhere. It’s not a business model that’s glamorous or sexy; it’s a slog, scraping together pennies, a reality that no amount of union activity is going to avoid.

Lynch, 61, does not have a background in journalism. He came to Condé in 2019. He had previously run the music-streaming service Pandora — he plays lead guitar in an all-CEO classic-rock cover band called the Merger — and was one of New Yorker editor David Remnick’s suggestions for the top job.

Lynch spent his first few years as CEO building out the in-house video studio, Condé Nast Entertainment. In 2020, he hired Agnes Chu, a Disney executive, to run it. This past October, he sent out a memo that Chu was leaving and CNE was being restructured. The memo included almost no explanation as to why this thing that Lynch had been touting as the future of the company was suddenly being disappeared.

His primary achievement has been in streamlining the international editions of the brands, refashioning the publisher into one global newsroom that reports to New York — and to Wintour. A lot of wasteful spending was cut, many of the more independent-minded foreign editors departed, and last year Condé moved out of Vogue House, the posh seven-story building in London’s Hanover Square that it had occupied for six decades. (In November, British Vogue published a sad farewell issue dedicated to all the fashion history that occurred there.)

The company says plans are to shuffle resources to promising areas of this newly consolidated empire: Lynch just opened an office in Dubai and is launching Condé Nast Traveler in Germany, and Wintour staged a “Vogue World” event in London last year for the first time (it’s coming to Paris this year). But there is only so much to go around, and it is the editorial staff back in New York who are feeling the squeeze. The U.S. titles have had to make do with a lot less for many years now, and this latest round of proposed layoffs feels to many like the breaking point. It has all contributed to the worry that Lynch still has little to no understanding or appreciation of all that must go into making magazine magic.

“There are a lot of execs who are very far removed from those who do the day-to-day work: the writers, the researchers, the editors,” Mallary Santucci, a 39-year-old culinary producer for Bon Appétit, said from the picket line. “A lot of their plans seem opaque,” concurred Gaylord Fields, a 63-year-old copy manager at GQ.

The shuffling and reshuffling has reached the point where Condé is now spitting out the people who were brought in to replace the prior generation of people it spit out. Vanity Fair seems particularly imperiled; ten of its editorial staffers are on the list of 94 doomed employees now circulating. “Everyone has been making do with nothing for years, so for this to happen, it’s like things might just come apart from here,” says senior correspondent Delia Cai, 30, who is on the list. “You would be shocked at how few people are holding it up.” How has VF’s editor-in-chief, Radhika Jones, handled all of this? “Radhika has been a real one,” Cai said approvingly. “I don’t think she has a lot of answers or clarity either. I think she’s saying as much as she can say but openly making her displeasure known as well.” I asked Cai whom she is most furious at for how things have been run. “It’s Roger, right?”

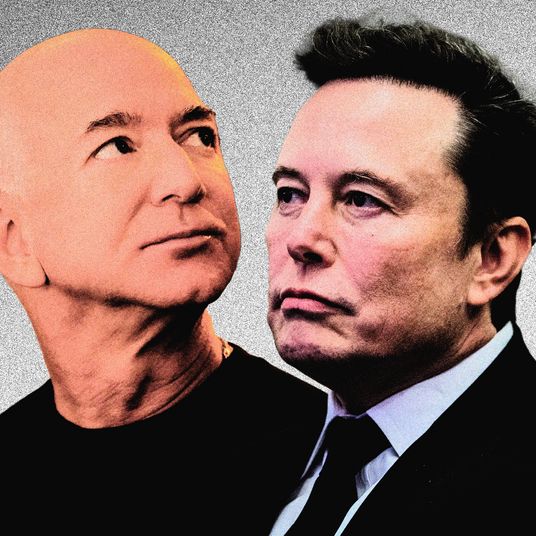

What makes this larger moment in media feel so hopeless is that many of the proprietors above the likes of Lynch appear wholly unconcerned with the way business is going. As Jeff Bezos shreds the Post, our Instagram feeds accost us with photos of Ivanka Trump and Kim Kardashian at his big Beverly Hills birthday blowout; every time Lauren Sanchez posts a freaky picture of herself at another tacky party or on a boat, you half-wonder to yourself, Is that where the newspaper’s “Metro” budget just disappeared to? Patrick Soon-Shiong, the hapless billionaire who owns the L.A. Times, allowed his meddling activist daughter to antagonize one of the most respected editors in the country, Kevin Merida, who, on the eve of brutal layoffs, finally just gave up. The Baltimore Sun was bought in January by a right-wing culture warrior who readily admitted he had never even read the thing before. It really is as it appears: The worst people are dancing together on the lip of the volcano as the journalists fall into the caldera.

But there was something particularly sad about watching the Condé people picket outside their brokedown palace in the cold. Manhattan is supposed to be the media capital of the world. What are we if we can’t even have one elite, glitzy magazine publisher? Wintour has her detractors, but plenty of people at the company told me they were reluctant to diss her, because, at 74 years old, she is still trying her damnedest to keep it all going. She seems to understand that media is a business, yes, but if you don’t have something worth selling — worth subscribing to or advertising with — it all falls apart. “It’s hard for her to see what’s happening,” says one of Wintour’s confidants inside the building. “But I think it’s beyond her job to fix this. We don’t know how it’s going to be fixed.”