This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In April 2022, Rob Curtis, the CEO of Daylight, a start-up billing itself as a new kind of bank for the LGBTQ+ community, invited more than 30 of his employees to his home in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, for a retreat. For weeks he’d been hyping the gathering, which he called “Diva Camp” and which cost more than $50,000. “We’re going to be so wasted!” the staff remember him saying more than once. “Are you ready to turn it up to 11?”

Curtis, an Australian who is more than six and a half feet tall with reddish-brown hair, lived with his husband-to-be in a beach-view villa named Casa Do Re Mi, with music notes adorning its wrought iron railings and walls. Daylight was registered in New York but had no fixed headquarters, and its employees mostly worked remotely. In Mexico, many of them met each other and their boss for the first time. “Let’s pretend we’re all white, cis, straight tech bros for a week,” Curtis said in a welcoming speech, and “at least allow ourselves the permission to celebrate in the way that they would.” Nearly half the staff identified as trans or nonbinary.

Curtis said there was a big new funding round to toast — but first there were team-building exercises, and they quickly got uncomfortable. For a “speed-dating” session, managers handed out white labels and instructed employees to fill in their identity, which led to workers wearing stickers that read “formerly homeless” and “sexual assault survivor.” On the second day of the retreat, the staff gathered for a session billed as “Take Pride”: Each participant was asked to share a personal experience that seemed bad at the time but in which they later took pride. The head of HR helped kick it off, relating a deeply traumatic tale. It set the tone for others, who began to reveal stories of abuse. One worker started visibly shaking.

The third and final day got weirder. “This is where it’s like Handmaid’s Tale meets queer bank,” says a former department head who was there. In his living room, Curtis presented a new vision for the company: Daylight would become a queer “marketplace,” expanding beyond banking toward fertility and surrogacy services. He’d been musing about the idea for months. “Let’s get all the gays donating sperm, and all the poor queer women being surrogates,” Curtis once wrote on Slack. “There’s a lot of poor queer kids who could make some easy cash. Kinda creepy but who are we to judge?” He also floated a potential tagline: “The bank that made me pregnant.”

In Mexico, Curtis spoke about how a generation of “Daylight babies” could have a meetup one day. “There’s no room for questions and no room for doubt,” he said about the new strategy, sitting on the floor, looking his workers in the eye. “You’re either with us or you’re not.” He invited anyone who wasn’t onboard to leave the company.

“I texted my friend in the room — I was like, ‘This is some real Theranos shit,’” says the former department head. “What the fuck is this? I’m not pledging my fealty to this guy.”

Later that night, there was a party. Huge inflatable letters spelled “DAYLIGHT” in the pool; later they were rearranged to say “GAY.” Drag queens performed the title song from Hedwig and the Angry Inch, and for a grand finale, Curtis had fireworks explode above the beach as Katy Perry blasted from a sound system. As one employee recalls, Curtis climbed atop a brick wall, stretched out his arms, and exclaimed, “We did it! The first LGBTQ banking company to close a Series A! We did it!”

The employee says, “I just remember going to sleep and being like — didn’t we not close it yet?”

The $15 million funding round, in fact, had not closed, and wouldn’t be announced for another seven months. The incident wasn’t the first time Curtis misrepresented the company’s data and finances, according to a lawsuit filed in federal court today by three former employees, who are alleging age and wage discrimination, whistleblower retaliation, and fraud.

One of the litigants, Terrance Knox, who is Black, says he made as much as $85,000 less than his white peers. The lawsuit also alleges that when Knox asked Curtis about the source of some figures in a document he sent to investors, including a projection that Daylight would process $500 million in transactions by the end of 2023, Curtis replied, “I made that shit up.”

Daylight and Curtis dispute those claims and others in the suit. “Daylight is fully prepared to address these concerns in court,” a spokesperson for the company said. The filing, in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York, is at least the second employee lawsuit against Daylight. Cristina Rodgers, the company’s former chief of staff, sued in California in August.

Many of the allegations in the lawsuit are corroborated by interviews with 15 current and former employees and a trove of their Slack conversations, screenshots, and other records. They say that in addition to mismanaging the company, Curtis was manipulative and created an environment that was “psychologically unsafe,” with precisely the kind of personal violations they thought they’d avoid by working at an LGBTQ+ oriented start-up.

“I’ve never experienced a more hostile environment, lie after lie,” says an employee who quit recently, feeling misled about the company from their first week on the job. “The way they treat people — it’s a very different sales pitch than is reflected internally.”

Others who worked for Daylight say Curtis misgendered them, used an employee’s dead name in a meeting, and broadcast another worker’s gender-affirming surgery to the staff without consent. The behavior seemed especially offensive coming from someone who held himself out as an advocate for diversity. “People called him Donald Trump,” says a former marketing employee. “You wouldn’t think this queer CEO that’s launched this mission-driven business would be that way.”

“We regret that some former employees felt disappointed that the company would not go beyond the scope of our mission and invest our resources in addressing systemic, societal issues affecting LGBTQ+ people. We’re equally sad that we could not meet their personal expectations of start-up culture,” Curtis said in a statement. “Like everyone else, diverse founders are human and the expectation that LGBTQ+ founders must be perfect is part of the reason that founders like us receive fewer VC dollars than non-diverse founders.”

What’s happened at Daylight is like a “what not to do” playbook for progressive, do-gooder start-ups seeking to change the world and make money in the process. Curtis and the company appropriated the language of wokeness, only to face a backlash when workers began to feel that it was all just an act, perpetrated on the population they had promised to help.

At first glance, the business case for a queer-focused bank has immediate appeal. The LGBTQ+ community has an estimated buying power of $1 trillion, but its members earn just 90 cents on the dollar when compared to the average American. Same-sex couples face mortgage discrimination and higher costs to have children; trans workers often deal with job and income instability as well as potentially higher health-care expenses. A bank that understands those factors and develops customer loyalty by helping them close that wealth gap could be quite valuable — either on its own or as a target for acquisition by a larger financial-services company.

The company that would become Daylight was started in 2020 by a Slovak entrepreneur named Matej Ftacnik. He brought in Curtis, who’d once worked at the U.K. dating site Gaydar, to become the chief product officer. “The pitch was rainbows on cards; free Grindr,” Curtis once said. Curtis in turn brought on two British executives, Billie Simmons and Paul Barnes-Hoggett, and the three eventually began referring to themselves as the company’s “co-founders.”

Their nationalities made some prospective hires in America suspicious. “All white people with accents,” says a former Daylight manager. “They’re giving off the most colonizer vibe they possibly could.” And yet the business opportunity seemed solid. “If you let me do what I know how to do, we will all be very, very rich and very, very gay,” says Jae Bleiberg, who joined the company in 2021 as head of operations after working at two prior fintech start-ups.

Knox, who lives in Brooklyn, also started at Daylight in 2021. He’d spent his career in corporate development and had also been active in queer-advocacy organizations for decades. He loved the idea of marrying the cause with a for-profit business and says he turned down a higher salary at another potential employer to join Daylight. “I thought that this one had legs and was actually going to make a difference in people’s lives,” he says. “I know what our struggles are. They were ringing all of the right bells for me.”

Daylight planned to offer loans for gender transition and to steer its clients’ spending to LGBTQ-friendly businesses, taking a small cut of the transactions. But one of its brightest selling points was to allow customers to put whatever name they chose on their neon-yellow payment cards, so they wouldn’t have to see their birth names every time they swiped. Daylight didn’t invent the idea — certain other banks and card companies already offered the service — but many people didn’t know it was possible.

The staff loved the feature. “That was huge,” says Bleiberg. “Getting a debit card that said ‘Jae’ on it was such a big deal for me that I showed it to everyone. I mean, not the numbers, but like, I showed it to everyone.”

Daylight’s employees were told that their preferred name, pronouns, and identity would be respected at work. For many, being at the start-up felt like more than just a job; they were fired up because they believed in its potential. Daylight definitely didn’t act like an incumbent bank. Its marketing materials talked about “Queering banking for the better,” and its social-media output was full of double entendres and often a little horny. “No size queens here!” read one tweet. “At Daylight, we celebrate your milestones, even if they’re small.”

Curtis made no claims to being a conventional CEO, telling workers that he’d been fired from several previous jobs, in part because “my behavior slipped. I was no longer willing to play the game in deeply conservative British banking.” He made it sound like he was a rabble-rousing advocate who tried to effect change from the inside. “He was like, ‘I’m a troublemaker. I’m usually in trouble with HR. I speak up and stand up,’” one ex-employee says. “It sounded to me like he was on the right side of history. And when I started, I was like, ‘Oh, no, I think it’s the other way. I think you’re problematic.’”

Before long, Knox — who’d previously worked at AstraZeneca and Vodafone, among other big companies — started to have doubts about what he’d gotten into. In July 2021, he attended Daylight’s first retreat, set some 30 miles outside of Indianapolis. “You got a house full of queer people in the middle of the country, and there were no locks on the windows or doors,” he recalls. According to his lawsuit, shortly after arriving, Curtis came over with a baggie of candies and suggested he take one.

“It’s my CEO — it can’t be that bad,” Knox remembers thinking. He took one. The Daylight staffers began playing a game called “Start-ups,” where players pitch ideas for ridiculous companies, and Knox started to lose it. “I’m just not feeling like I can even speak,” he says. “And Rob’s, like, pointing and laughing.” Knox says he began having a panic attack and chest pains, wondering if the edible had been laced with more than weed. (Curtis disputes Knox’s account and says that another employee handed out the candy.)

The next day, as they rode home from a bar with some other staffers, Curtis began confiding stories about his youthful party days, when he would take the date-rape drug GHB and sometimes witness scary moments. “I know how to get someone out of an overdose,” Curtis assured his colleagues in the car. “I have the DJ play ‘Toxic,’ by Britney Spears.” Knox felt alarmed. “We’re all like, Why is our CEO talking like this? We don’t want to hear this. This makes me feel less confident in you as a leader. And in my mortgage. I owe my maintenance. I need you to be stable.”

Other employees also say Curtis crossed boundaries. Emmett Burns, now 24, applied for an internship after hearing about Daylight’s trans-friendly policies. “Having a name that’s different from your legal name was not going to be an issue, and that was important to me because I’m transgender,” he says. According to the lawsuit, on his first day, during a one-on-one meeting, Curtis asked repeated questions about why Burns’s résumé included work with victims of physical and sexual abuse, until Burns acknowledged that he was a survivor.

“Rob responded to that by giving me a really graphic story of an assault that had happened to his friend on Grindr,” says Burns. “I almost quit after that meeting because it was so uncomfortable.” He told Curtis that he didn’t think the episode was his to share.

Curtis also disputes this account, saying he never questioned employees about assault or trauma. In a second emailed statement, he added, “I can certainly be a demanding boss and I hold my team to high standards, but I also realize that the language I use and the leadership style that I brought into Daylight did not always bring out the best in others, and at times I may have been too casual in a professional environment, and for that I am sorry.”

In October 2021, Daylight’s head of product, Ethan Teng, suddenly quit, lambasting the company in a public LinkedIn post. “I was extremely disappointed by the circumstances that led to this decision,” he wrote. “In the end, it came down to staying or choosing to double down on myself: my integrity and self worth.”

At the beginning of 2022, employees noticed that meetings were scheduled for Martin Luther King Jr. Day. According to the ex-employees’ lawsuit, Curtis confirmed that Daylight would not observe the federal holiday. One former employee says that when staffers questioned his decision, he heard Curtis respond, “Well, the Blacks already have Juneteenth.”

“It was microaggression times ten,” says the employee. “He was completely unaware that how he worded it was racist.”

Curtis says he never made the remark. A Daylight spokesperson says that in 2021, the staff voted on which holidays to observe, omitting MLK Day, and that “unfortunately the flexibility in this policy was not well-communicated to employees.”

After the incident, Daylight’s chief of staff, who was Black, resigned.

One reason Curtis lived in Mexico at the time was that he did not have a visa to legally work in the U.S. But he made occasional trips to Manhattan, and by early 2022 his behavior grew erratic, employees say. He berated workers, often in front of their colleagues, for spending time on projects he’d assigned just a week before, and he kept managers from seeing essential company records like pitch decks and budgets.

Curtis was also starting to be conspicuously unavailable, telling staff not to contact him while he was gone. The company says he never took a mental-health day, but workers don’t remember it that way. “Every other week it seemed there was a reason for him to take another week off for mental-health reasons, that something triggered him,” says Brittany Canty, a former Daylight executive. She recalls Curtis breaking down in tears during a rooftop-drinks session at the start of the year, while venting about the stress of raising investment and securing a visa.

At the Puerto Vallarta retreat that April, Curtis spoke openly about his struggles. “I’ve been living with income insecurity because I’m not yet able to draw a consistent salary from this business,” he told the staff, one of whom was recording audio. “I have no employment contract, I have no health insurance, I have no community around me. I have no guarantee that I’m going to be allowed into the country to do my work. Having housing insecurity sucks.” Curtis also spoke about being “bullied” by investors and his fears of being “canceled for being a white cis gay.”

He also let on that Daylight’s origins might be more complicated than most of them knew, describing his efforts to take over the company from Matej Ftacnik as a “coup,” and saying that he handpicked Simmons, who is trans, in part because she “presents great optics.” Curtis urged the staffers to be discreet. “It’s important that this is not presented to the outside world as a messy story,” he said. “We don’t get the opportunity to be messy. We don’t get the opportunity to have a coup internally of gays stealing from gays.”

Canty was among the workers who found the subsequent “Take Pride” and loyalty-pledge sessions extra unsettling, given that they were in a foreign country and were relying on company-paid flights back to the U.S. “You were literally in Rob’s home,” Canty says. “You couldn’t leave if you didn’t want to partake.” Knox describes Curtis’s “You’re either with us or you’re not” remark as a “David Koresh moment.”

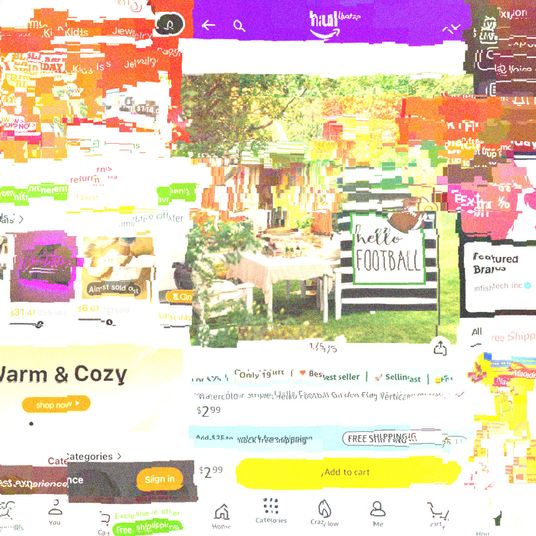

After weeks elapsed and the Series A funding Curtis falsely touted was not announced publicly, employees began questioning other things he’d said, such as a claim that Daylight at one point had a wait list for its app 100,000 people long. But many of the emails didn’t work, and according to one employee, only about 2 percent of recipients clicked through. The app debuted in November 2021; by June 2022, there were only a few hundred active users.

One of them was Curtis. Several employees told me that he used Simmons’s name and Social Security number to open a Daylight account, which he used while living in Mexico. Dillon Welch, then an engineer at the start-up, was on bug duty when they discovered the issue; Curtis had messaged customer service asking to change the email and phone number on the account. “I was like, Hey, this is not right. This account was opened well before you were processed as a person in America,” says Welch. (Daylight says it was a “test” account opened “with the permission of our compliance and banking partners” as well as Simmons.)

“Something you would hear a lot is, ‘I know how to bury the numbers so no one is going to really look at this,’” says a former employee. In the middle of 2022, research staff became aware of a press release that was about to go out touting a survey with 1,500 people about LGBTQ+ banking. The workers raised concerns, saying they were aware of no such survey and were worried the data was made up. One wrote to another on Slack: “I just spoke with Rob over the phone. He said it’s ok in this instance since we need to mention a more significant pool of people so I guess we’re just going to go with it for this one knowing that the likelihood of a fact check on our internal data is not likely.”

Daylight put out the numbers. On June 10, Fast Company published an article about the data under the headline “Study: LGBTQ Gen Zers are ditching the ‘boomer approach’ to money and finance.” After I asked the company for comment, a spokesperson acknowledged that the data had been “fabricated.”

On the workday after the Fast Company article, about a dozen Daylight employees, including Knox, Canty, and Bleiberg, were laid off in a brief Zoom. During the meeting, Curtis disclosed that the company had just $1.47 in revenue.

Daylight’s primary product now is Daylight Grow, “a financial and family planning product designed specifically for queer families.” It offers a free subscription service for surrogacy, adoption, and fertility financing tools, and earns revenue through affiliate fees when it connects customers to outside vendors. Daylight’s banking app, Daylight Money, still works for those with existing accounts, but new sign-ups are limited to those who join the Grow program. The investors that I spoke to said they remain confident in Daylight’s future.

In their lawsuit, Knox, Canty, and Welch are seeking unspecified damages. “This is about Daylight exploiting the LGBTQ+ community for its own gain, and really exploiting investors as well,” says their lawyer, Tyrone A. Blackburn. “What we’re looking to do is to hold Daylight accountable, and to see that their company mission is actually upheld.”

“Even though this bank was supposed to be helping people, it felt very predatory in a lot of ways,” says Canty. What transpired at Daylight shows how the guise of a noble corporate mission can provide cover for a CEO behaving badly. “He was in a way weaponizing being marginalized against to tell us we had to succeed and be excellent,” one former Daylight staffer says of Curtis. “We all convinced ourselves it was normal, because we were working on something we believed in.”