Here’s an experiment you can run yourself. Open up a category on Amazon — Electronics, Toys, Home Garden & Tools, whatever — and scan the first page for a product listed with no obvious brand, or perhaps a semi-brand like IOCBYHZ, BANKKY, or KLAQQED. Take a look at the product photos and description, and note the price. Next, try to find the product on Temu, the discount app with the Super Bowl ads, and check how much it costs. Next, try to find it on AliExpress, the international e-commerce subsidiary of the Chinese Alibaba Group, or on TikTok Shop. Finally, you can look for it on Alibaba proper, where it might be available as well, shipped straight from China.

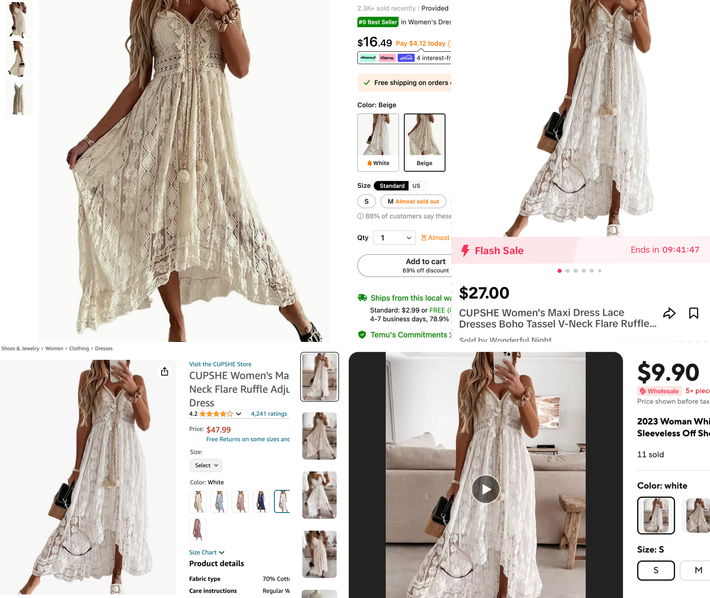

Sometimes, not always, but more than you might expect, this works. Take this dress from CUPSHE, listed on Amazon at $47.99, with more than 4,200 ratings, mostly positive. On Temu, where it also ships for free from a “local” (read domestic) warehouse, it’s listed as “Womens Casual Boho Lace Hem Floral V Neck Long Beach Dress Cocktail Party Maxi Wedding Dress” and costs just $16.49. On TikTok Shop, it’s on Flash Sale with free shipping for $27 dollars. On AliExpress, it’s available at lots of prices from different sellers, for $9.90 with $9.60 shipping, or, on promotion, shipped free with an alleged 85.2 percent chance of arriving within 14 days for $8.66.

I didn’t order these dresses, so I can’t verify that they’re exactly the same or that one isn’t a rip-off of another, nor do I know enough about boho maxi dresses to tell you if these are a rip-off of a design from outside the discount e-commerce world.

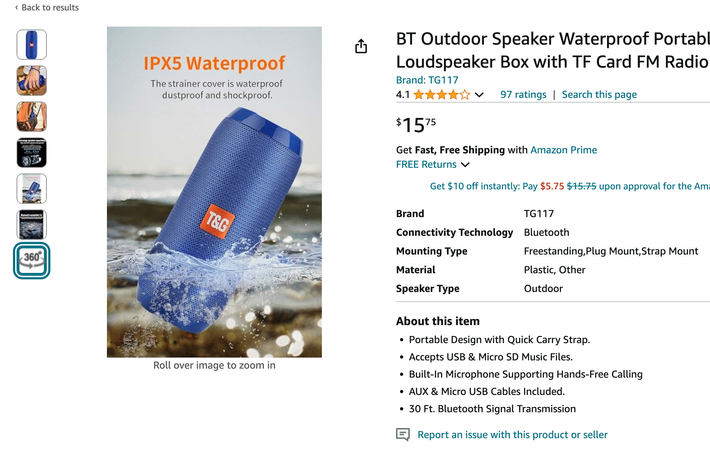

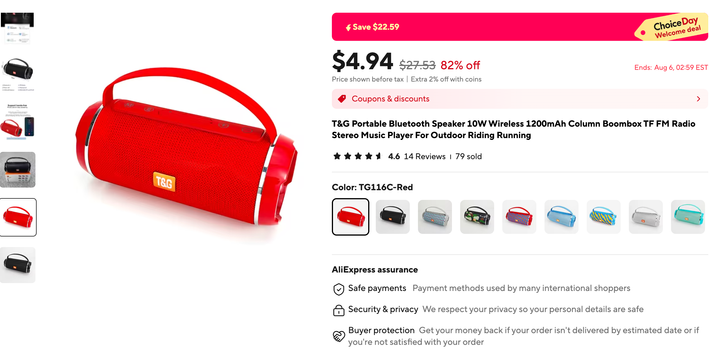

But again, this isn’t uncommon. One popular speaker, for example, branded as T&G, is $15.75 on Amazon, $8.38 on Temu, and $4.94 with free shipping on AliExpress. It’s clearly … inspired by popular speakers from 78-year-old company JBL, which also sell on Amazon, albeit for $89.95 on steep discount.

The process works across categories: A pair of bike shorts goes from $19.99 to $11.77 to $2.30; a folding utility wagon goes from $95 to $38.99 (indistinguishable from the one our family purchased on Amazon in 2023 for $110.59). Are these the exact same products? Maybe, and in many cases probably. It’s possible they’re made from the same reference designs by different factories; in other cases, they might be sold by the same sellers on different platforms.

But for anyone willing to take a little time to comparison shop across big online stores, it’s clear something is happening: Amazon is becoming more like Temu, TikTok Shop, Shein, and AliExpress while Chinese e-commerce platforms are becoming, in America at least, more like Amazon. The big stores are all selling the same brandless imports from China, sometimes at wildly different prices, and converging on similar logistical strategies: Temu is shifting seller inventory to American warehouses to reduce shipping times; Amazon is planning to launch a dedicated discount section with products that ship from overseas in about a week.

In the broadest sense, this is pretty familiar stuff. Different stores offering some of the same products at different prices with different levels of convenience is the story of big-box physical retail and grocery stores, too. But this is different in some ways that are obvious and others that are more subtle. These aren’t chain stores offering occasional discounts on branded products with MSRPs but rather marketplaces full of sellers who are individually pricing anonymous products based on fluctuations in warehousing rates, shipping, and the cuts taken by the e-commerce platforms. Additionally, the products we’re talking about range from junk to solid unbranded alternatives — this is, across the board, discount shopping. You might score a 90 percent discount on a fast-fashion shirt or some home-décor dupes, but you’re not going to get a shocking Temu deal on, say, a PlayStation, although you can buy them there, which wasn’t really true when it first launched.

These companies are approaching the same e-commerce strategy from very different positions as well. Temu, an international subsidiary of e-commerce giant Pinduoduo, is spending heavily to break into foreign markets including the United States, in many cases subsidizing shipping and prices and reportedly operating at a massive loss; AliExpress has been making slower inroads with its product, which is more overtly a cross-border whole-adjacent marketplace, with long shipping times and minimal domestic marketing.

Amazon’s drift into cross-border e-commerce predates the likes of Temu and these other competitors. Since the late 2010s, a majority of Amazon’s sales have been attributable to third-party sellers, many of whom pay substantial fees to the company for logistical support (warehousing, shipping) and advertising. This strategy has been great for Amazon in a lot of ways: It shifts market research and risk to sellers; rather than stocking their own products, the company charges sellers to stock theirs; the company is now the third-largest player in digital ads, behind Meta and Google, owing mostly to fees it charges Amazon sellers to be visible on Amazon. It’s also changed the product in more complicated ways. American sellers, many of whom sourced or manufactured their products overseas, soon found themselves competing with sellers with more direct connections with Chinese factories; Amazon, for its part, courted overseas sellers. American sellers were made to look like middlemen, which in some ways they were — the companies they were building were less brands than high-ranked-and-reviewed Amazon listings, and the manufacturers they worked with knew exactly what kinds of margins they were getting.

Now, something similar is happening to Amazon as a whole. While the platform has been moving downmarket, becoming more hostile to name brands whose products are being undercut and in some cases plainly ripped off, China-based competitors are attacking it from below, working with some of the same manufacturers and sellers to cast Amazon as the middleman with needlessly high prices. While Amazon initially pushed into cross-border e-commerce on its own terms, now it’s doing so defensively.

Amazon still has huge advantages here. It’s profitable, widely liked and trusted, and still used by tens of millions of Americans to buy mainstream products from recognizable brands. Customers who use it to buy an occasional CUPSHE dress, on which Amazon and a third-party seller are collecting huge margins, are likely to be buying batteries or detergent, too. And no company, foreign or domestic, can come close to Amazon’s Prime shipping infrastructure.

But there are obvious risks, too. Customers like cheap things, but they like cheaper things more. It’s not clear that Amazon can profitably win in a race to the bottom, or that it won’t damage its reputation trying. Amazon risks making its marketplace fully uninhabitable for more established brands and hostile to domestic sellers, some of whom have called its Temu-ish plans a “slap in the face.”

Then there are customers. An ornate $9 dress on AliExpress is an ethical and environmental nightmare, a semi-disposable garment of sewn-together externalities. But so is the one on Amazon — which is also something worse, at least in the eyes of the marketplace: a really bad deal.