This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

It was a Saturday afternoon in mid-March, and John Avlon was comparing himself to a Norman Rockwell painting. “You know,” he told me, the one where “there’s the guy standing up in a town hall — like an old-school town hall?” The picture he’s painting himself into, in his mind, is called Freedom of Speech. It was one of the “Four Freedoms” paintings, based on Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union address (the other freedoms being of worship, from want, and from fear). What could be more agreeable and all American than any of that?

We were standing in front of what is literally an old-school town hall, built in 1731, in Jamesport, out on the East End of Long Island, where Avlon, 51, is running for Congress in New York’s First District. You might know him from his years of saying utterly conventional things on CNN, where he was a political analyst, and from the occasional Bill Maher segment; from 2013 to 2018, Avlon was also the editor of the Daily Beast. The town hall that day was filled with mostly elderly locals who’d turned up to get a good look at this grown-up Boy Scout with throwback centrist politics and a sheen of minor TV fame.

Avlon had for years vacationed in nearby Sag Harbor, the prosperous, historically preserved village that is a summer home to many of the city’s media gentry who can’t quite afford to live among the real moguls of nearby East Hampton. In 2017, he bought his vacation house and is now using it to launch a mid-life political career. He lives there with his wife, Margaret Hoover, 46, a Republican who is the host of PBS’s Firing Line (as well as the great-granddaughter of President Herbert Hoover), and their two kids, ages 8 and 10. “Now I’m here full time,” Avlon said. “I’m here whenever I possibly can be because this is an awesome place.”

He is running in the Democratic primary on June 25, positioning himself as the best hope to flip this district, currently held by a first-term Republican named Nick LaLota. Avlon’s (earnest) pitch is essentially this: After years of our politics being warped by polarization and showboat extremism, it’s time for a return to something like “the third way” of the 1990s, when President Clinton was successfully triangulating (Avlon volunteered for Clinton’s campaign) and the not yet so obviously nuts Mayor Giuliani was “cleaning up” New York (Avlon worked for him as a speechwriter).

Avlon is so committed to this dream that he helped found the political group No Labels in 2010, though he left it in 2013, the same year he began running the Daily Beast. At the town hall, he described No Labels’ interfering in this presidential cycle as being “absolutely disgusting and dishonorable.” (A couple of weeks later, on April 4, No Labels decided not to nominate a candidate.)

His opponent in the Democratic primary is Nancy Goroff, an organic-chemistry professor at Stony Brook University who ran for the seat in 2020 and lost. Avlon and Goroff share similarly mainstream Democratic policy positions on things like abortion rights and supporting Ukraine. But Avlon is unquestionably more polished than Goroff and is pitching himself as being the better bet against LaLota and the Trumpist Republicanism he represents. “I really have devoted most of my career to warning about the dangers of hyperpartisanship and polarization, as a journalist, in my columns and books,” Avlon told the crowd at the town hall. “I went to Yale,” he began … but then he seemed to think better of it. “By the way, I don’t like when people talk about where they went to college ’cause I think it’s kind of annoying.” A Republican tracker sat in the back of the town hall, filming, hoping for a “gotcha” moment.

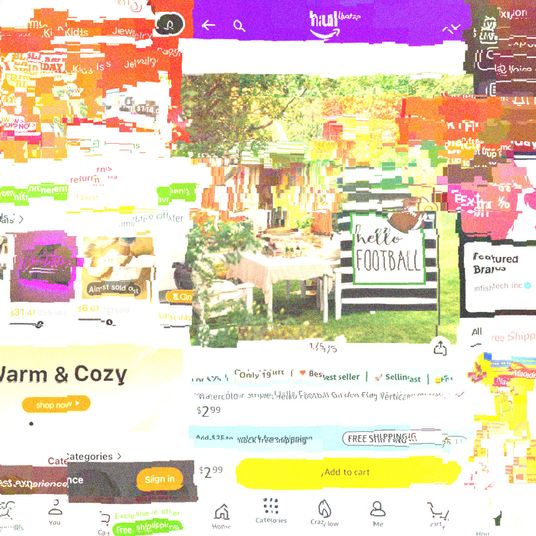

Avlon’s city-boy privilege is already on the list of the Republican talking points against him. Many members of the Manhattan elite have summer houses in the district, but it’s still Long Island, which runs pretty red these days. Avlon is not even the first Manhattan media insider with a weekend house out east who has fantasized about representing this district. In 2018, his former boss at CNN, Jeff Zucker, considered a run. He even had the political firm SKDK do polling without using his actual name.

Powerful people have lined up behind Avlon. His donors include Joel Klein and Reid Hoffman, Dan Loeb and Richard Plepler, Eric Schmidt and James Murdoch. “There’s a retail niceness about John,” said Barry Diller (another donor), who owns the Daily Beast.

In some sense, for these elite friends, the idea of Congressman Avlon would really just be him coming into his own — manifesting his destiny. “I was always trying to persuade him” to run for office, said Tina Brown, who was his predecessor as editor of the Daily Beast. “He’s always felt like a congressman,” said journalist Ben Smith, with whom Avlon worked at the New York Sun in the early aughts. “The first time I met him, I thought he might be a congressman.”

Avlon peppers conversation with patriotic platitudes and factoids of American history, and he’s constantly quoting the Founding Fathers or some long-ago president. He wrote a book about George Washington and one about Abraham Lincoln. “He’s so red, white, and blue, so well spoken, that at first you can be tricked into thinking it’s an act,” said Noah Shachtman, who was Avlon’s deputy at the Daily Beast and succeeded him as editor. “I can assure you it is not an act.” Or, as Bill Maher put it to me: “He’s more of what we need in politics — boring!”

But can boring still win? These are mad times, and in politics – as in cable news – crazy plays. Avlon is available to run for Congress in part because he never got a bigger job at CNN; he always wanted a show of his own, but that didn’t happen. He quit the network in February, with a few months left on his contract, to run for office. His candidacy now seems like a case test: If you run a perfectly reasonable, media-trained golden retriever of a man who talks like a Clinton Democrat crossed with an extinct breed of pragmatic big-city Republican, will voters go for it?

After the town hall, Avlon hopped into his Volvo XC90 SUV with an aide to drive to their next event, a campaign kickoff speech in Sag Harbor. I asked him where in the city he grew up. “A little bit on the East Side,” he said, coyly, “a little bit on the West Side.”

By the East Side, he means 1160 Park Avenue, a white-glove co-op building in Carnegie Hill. His father, John J. Avlon, ran a real-estate firm whose investors included the Goulandris family, heirs to a Greek shipping fortune.

Young Avlon was nicknamed “Fipp,” after his middle name, Phillips, which was his mother’s maiden name. For grade school, he attended Buckley on the Upper East Side. For high school, he went to Milton Academy, a boarding school in Massachusetts. When he was 14, his parents left the city and relocated permanently to Charleston, South Carolina (the father would travel to Manhattan to do his real-estate deals). “It was the late ’80s. The city was in a little bit of civic disarray,” explained Avlon. “They said, ‘Well, let’s move.’ They were able to trade an apartment for a house.” He would visit his mother and father in Charleston when school let out, but he never fully lived there. He speaks today with a vaguely folksy twang he claims to have picked up from his teenage summers in the South; when he says “Nick LaLota doesn’t want to run against me,” it comes out sounding like “Nick LaLota dunnuh-wunnuh run against me.”

When Avlon the candidate talks publicly about his background, he says simply, “I’m the grandson of immigrants. It’s why I’m so patriotic.” (Both his parents’ fathers were Greek immigrants). He’s cagey about his privileged upbringing. He acknowledges that “he’s had a lot of opportunities,” but I don’t get the sense he’s secretly Über-wealthy. His place in Sag Harbor is a three-bedroom, two-bathroom single-story house that he purchased for about $1.5 million. “I’m a journalist and a writer,” he said. “My grandparents and parents really did achieve the American Dream, and look, no, I’m not Über-wealthy.” (Avlon’s house in the city is a duplex apartment near Gramercy Park, which he purchased for $3.6 million in 2015; it’s part of a brownstone that was once owned by Robert Winthrop Chanler, a member of the Astor family.)

In 1973, Avlon’s father and the Goulandris group began to buy up, bit by bit, all of 61st Street between Central Park and Broadway, which included the Mayflower Hotel. By 1978, the firm owned the entire square block. They held onto it for decades, as plans came and went to redevelop Columbus Circle just to the south. In the mid-1990s, Donald Trump bought the old Gulf & Western office building and turned it into one of his bronze-glass residential towers. He wanted the Mayflower site, too. According to Michael Gross’s book House of Outrageous Fortune, about the development of 15 Central Park West, Trump’s brash attempts offended the gentlemanly sensibilities of John J. Avlon, who told Trump not to even bother trying. “The contrast between the two men could not be clearer,” the younger Avlon said of his father. Gross told me that Avlon’s father was “elegant, restrained, soft-spoken, diplomatic,” recalling his Brooks Brothers shirts, good cuff links, and their meetings at the Harvard Club.

As the neighborhood was refashioned, the Goulandris plot became some of the hottest real estate in the city, the western pole of what would eventually become Billionaires’ Row. Anyone who wanted it — and many did — had to go through John J. Avlon. Finally, in 2004 (the year the massive AOL Time Warner Center opened in Columbus Circle), he put together a monster deal, selling the land for $401 million to a consortium led by the Zeckendorf family and Goldman Sachs. The Mayflower was razed, and 15 Central Park West went up in its place. “Avlon really was engaged in alchemy,” said Gross. “He took a fucking slum and he turned it into the most-sought-after real estate in the world.”

In 1992, young Fipp was off to Yale, where he got his first taste for politics, volunteering for both of Bill Clinton’s campaigns. “I’ve never been a Republican,” he said a few weeks after the town hall. We were meeting for lunch at the Main Street Cafe, in the small East End town of Northport. “I was a Democrat in college when I started,” he said, sipping an iced tea. “Bill Clinton’s campaigns were formative. This third-way approach to politics always made a lot of sense to me. I think you can track that through my politics. Rudy was a third-way mayor of that era. It was a whole generation, actually.”

He arrived at City Hall to be a speechwriter in 1998, when he was 25 years old. Avlon said that, in those days, Giuliani was “uncommonly thoughtful. If you asked him about his position on abortion when he had downtime, he would start talking about Saint Thomas Aquinas. His Manhattan College jesuitical education was close to the surface, and the pure love of the law — the Italian American who took down the mob. It was incredibly admirable.”

Just like at boarding school, he was called Fipp around City Hall, too. Some old colleagues from the time recall that, back then, Avlon already seemed like a congressman. “It was like every time he spoke, it was with the assumption that 20 people were listening,” said one person who worked closely with him at City Hall. “It felt like every statement was a Statement with a capital S.” Bruce Teitelbaum, who was the mayor’s chief of staff at that time, said, “He was a dedicated person who enjoyed what he did. Always had a smile on his face.”

On 9/11, Avlon watched from the fifth-floor walk-up at 24 Cornelia Street that he shared with a girlfriend as the first plane went overhead. He made it to the front steps of City Hall by the time the first tower fell. Avlon and three other colleagues wrote eulogies for firefighters and police officers — nearly 400 for the mayor and his surrogates to give over three months. Avlon said that, apart from having children, being in government after 9/11 was “the most formative moment” of his life.

“Writing eulogies afterward taught me you don’t have to be perfect to be a hero,” he said. “What matters is you do the right thing when it matters most.”

After City Hall, Avlon became a columnist at the New York Sun. Ben Smith, who now edits Semafor, was working there at the time, too. “Fipp was the first person I’d ever met that helped me understand John Lindsay and Nelson Rockefeller Republicanism,” said Smith. “He’d worked for Giuliani, but I knew lots of people who worked for Giuliani who had this sort of pugnacious chip on their shoulder, people like Vinny La Padula. A lot of them represented the sort of white, ethnic outer-borough voters who supported Rudy and had a lot of resentment of the Manhattan elites. Fipp didn’t have any of that … To me, he represented, even then, what felt like a vanishing thread in the Republican Party.” Smith called Avlon “a real moderate and institutionalist” and said he’s always “had a reverence for history in a kind of — and I mean this as a compliment — Jon Meacham way.”

In 2004, Avlon published his first book, Independent Nation: How the Vital Center Is Changing American Politics. It was the beginning of his 20-year media campaign for bipartisan pragmatism. He went back into politics to work again for Giuliani, who was preparing to run for president. “There was a feeling among those of us who’d worked with him after 9/11 that if he ran for president, we would all get the band back together,” said Avlon. “Remember, at the time, not only was he in such internationally and almost bipartisan esteem, but he’s a pro-choice, pro-gay-rights, pro-immigrant, pro-health-care Republican. It’s inconceivable.”

It was in the early days of Giuliani’s campaign that Avlon met Hoover. In 2006, she came up from D.C. to interview for a job on Giuliani’s PAC, Solutions America. “The PAC was pretty cheap,” she recalled. “They couldn’t put me up anywhere, and they were trying to find cheap hotels, which were all sold out” because of a violent summer rainstorm. “So the first night I met him, I spent the night on his couch,” she said. They stayed up late talking, and he gave her a copy of his book touting centrism. “I took home a copy and annotated it thoroughly because I disagreed with it so vehemently,” she said. “I had worked for Karl Rove in the White House; that was very much blue state and red state. There was no centrism changing American politics in that cycle.”

She was in a relationship at the time, but there was something about Avlon that appealed to her. “He was like this idealist who was like, ‘No, we have more that unites us than divides us,’ and I thought it was very endearing. And very naïve,” she said. “He’s very Aaron Sorkin. It was very West Wing. And I love the West Wing, and also hate it, because it’s so naïve. But in his case, I was like, Wait a sec, he really believes this.” Her relationship ended naturally several months later, after she’d started working for Giuliani, then she began dating Avlon. Their first weekend away together was spent at the American Hotel in Sag Harbor.

All that was before Giuliani — who, let’s face it, was never all that interested in being some great uniter — became a paranoid goblin, thoroughly disgraced by this thirst for money and power. “He used to say, ‘To be locked into partisan politics doesn’t permit you to think clearly,’” said Avlon. “He got locked into partisan politics, then he stopped thinking clearly. He really earnestly believed the law is a search for the truth. Then you run that up against what he did for Donald Trump after the 2020 election; it’s almost impossible to reconcile. It’s a real tragedy. Not that he was a perfect person, and he would never claim to be a perfect person. That was one of the refreshing things about him.”

“Perfect is never on the menu,” Avlon added. Still, for all his former boss’s flaws, Avlon said it was surreal to have to publicly turn against him on CNN. Avlon is also a key commentator on Giuliani: What Happened to America’s Mayor?, a four-part CNN docuseries on Max that showed how, as Avlon put it, his former boss “lit his legacy on fire.”

In 2008, after Giuliani’s campaign went bust, Avlon began writing columns for Politico. He was supporting Obama and appearing on cable news to talk about it when he met Tina Brown. She had, with Barry Diller’s backing, just launched the Daily Beast, a scrappy digital publication named after the fictional London newspaper from the Evelyn Waugh novel Scoop. “I first picked him up in a Fox green room,” Brown recalled. “I just thought he was very entertaining. I said, ‘You should write for the Beast.’ Then he became a real Beastie and he joined us on staff.”

He began covering what he calls “the extremist beat,” reporting on the political fringe; it was a subject he arrived at because he’d been “darkly fascinated” by 9/11 Truthers, he said. His reporting on “proto-tea-party stuff” at the Beast turned into his second book, Wingnuts, which he cites now that he’s running for office, arguing it gives him a good understanding with which to take on “the MAGA minions.”

At the Beast, Brown eventually put Avlon in charge of Washington coverage and, she said, “discovered what a very good executive he is. Very organized; the team loved him. He knew how to run stuff. Once that was clear, it was obvious that he should follow me.” But it wasn’t obvious how to make the Beast work. Brown had convinced Diller to buy Newsweek in 2010 and attempted to fuse it with the Beast. They burned through $100 million, and by 2013 Newsweek was sold and Brown departed. “He became editor because he was the best person standing at that time,” Diller told me. “And he wanted it. And when people want things, I care more about their will than about their experience.”

“It was a bit of a battlefield promotion,” said Avlon. “There were a lot of layoffs, necessarily, and there was a real question of whether the Beast could succeed.” He commissioned columns from voices across the political spectrum, having hired Obama speechwriter Jon Favreau as well as Republican operatives Rick Wilson and Stuart Stevens, and brought in new talent too. “Jamelle Bouie, I hired after one tweet in the 2012 election I saw,” said Avlon. He liked being the boss, and, as many of his former employees attest, he was pretty good at it. “Harmless cringe” is how one of his former reporters described Avlon’s management style. He had painted on the walls of the office inspiring quotes about journalism, the newsroom equivalent of putting “Live, Laugh, Love” signs everywhere. There was one from Ben Bradlee, one from Molly Ivins, and the one Avlon came up with himself: “We love confronting bullies, bigots, and hypocrites.”

As a former Beast reporter put it: “He does not have an ironic bone in his body.”

There were other ways money had been spent wildly at the Beast. In the NewsBeast era, they built a TV news-desk set onto the Beast floor of the IAC Building. Avlon did a daily internet newscast for an audience that, one former staffer joked, “must have numbered in the tens. I have vivid memories of Avlon using this Potemkin setup to practice for a future TV career. He was conspicuously good at it: the smarm, the fake paper-shuffling, the plummy comment segueing from one segment to the next.”

Back in 2010, Avlon had become a contributor on CNN, appearing whenever he could to offer political analysis. It soon became clear that TV was his preferred medium. “Somebody once said writing is like having homework for the rest of your life,” he said. “There’s always more to be done. With TV, you’re on, and then when you’re off, you’re off. You get to really focus, make a point, be a fully formed human. Yes, I just enjoyed it.”

In 2018, he quit the Beast and joined CNN as a full-time anchor and political analyst. Jeff Zucker was running the network, Trump was president, and business was good.

Avlon and Hoover wed in 2009, when he was 36 and she was 31. He proposed at the tip of Manhattan, with the Statue of Liberty behind them. “He won me over,” Hoover said with a laugh.

The couple would often appear on CNN together and created an Instagram called “Hoovalon,” on which to post clips of their time onscreen together. “Friends sending me snapshots of our contention on air calling it the cutest thing …” reads the caption of their last post from January 2023. “The crew at CNN named us that,” said Hoover. (The account has 1,149 followers.)

The couple shot a pilot at CNN, but it never went anywhere. Their Carville-Matalin shtick never stuck. Maybe it’s because, on air, they mostly just seemed like happy, well-adjusted people whose politics were basically indistinguishable. “We’re not going to be performatively fighting. It’s not authentic to who we are,” said Avlon. Hoover said they disagreed a lot during the Obama era — “the Affordable Care Act, foreign policy, the red line in Syria. I was much more Mitt Romney 2012, and he was not” — but that, politically, “Trump has definitely brought us together.” I wonder if the couple ever considered running her for office instead of him? “That would totally misrepresent the kind of conversations we have in our relationship,” said Avlon. “No, there’s not this, like, Who’s going to run? No. That’s not the way we talk or think. This was a long conversation we were having.”

In 2018, Hoover became host of PBS’s resurrected Firing Line. Avlon felt he was in line for a show of his own at CNN. He filmed some more pilots. After Zucker was pushed out, Chris Licht came in and yanked Brian Stelter, host of Reliable Sources, a show devoted to media criticism. Avlon was in talks to take over that spot and create his own show based on weekly video segments he was already doing called Reality Check: Extremist Beat, about disinformation and political extremism. But that didn’t happen either.

“I don’t think he had the real hunger, insecurity, and self-loathing needed to make it in TV,” theorized one friend of his. “He’s too happy and comfortable to win at television.”

“I never understood why John was so enamored of television,” said Brown. “For the last three years, I kept saying, ‘What are you doing, sitting at this desk at CNN? It’s ridiculous. You should be running for office.’ He said, ‘Oh, maybe I will sometime. Maybe I will.’ Actually, his TV experience is probably a very good training for running for office. I really do think he’d make a great pol.”

And so, if not out of work, but out of hope for TV stardom, he decided to run. I told him I had an admittedly cynical question: What would he say to someone who might think the entire reason he’s running for office is because he didn’t get his own TV show? “God, no,” he said, looking horrified. “That is an incredibly cynical question.” His career arc is sort of an inverse of how politics and media typically intersect: Many members of Congress understand that saying crazy shit is how you stand out and get on TV. It is unusual for TV people to refuse to say crazy shit and then run for office. And, as everyone keeps reminding me, he really does believe this stuff. “As a journalist who’s been chronicling the crazies for a long time and has covered two Trump cycles,” he said, “this is one of those times in American history where I think every generation needs to step up and defend democracy. And that’s what I’m trying to do in my own way.”

His chances to beat Goroff seem pretty good. “I think I’m leaning toward Avlon. His presentation seemed a little stronger,” said Sue Nobile, a 69-year-old retired schoolteacher who was sitting in the bench behind mine at the town hall in Jamestown. Amei Wallach, another voter at the town hall, was initially more skeptical: “I think the combination of New York and the Hamptons is poison in Brookhaven, and Brookhaven is all that matters. That’s where the voters are, where the numbers are.” But after listening to Avlon talk a while, she decided he was “very convincing” and said “he comes across as a politician, but he comes across as a very smooth politician.” He’s secured many endorsements from local Democratic groups, and he’s already outraised Goroff.

But the general election will not be easy. The first district stretches across much of Suffolk County, from Montauk and the Hamptons, up along the North Shore out to mid-island, around Huntington. LaLota took it over in 2022, after his fellow Republican Lee Zeldin gave it up to run for governor against Kathy Hochul (and came much closer to winning than anybody thought possible). And the recent voting history runs red. The seat hasn’t been held by a Democrat since 2014. President Biden was up by 0.2 points here in 2020, but in the 2022 midterms (when LaLota won), the district swung by 11 points for Republicans. And last month, a slight redistricting made it a shade redder. According to the Cook Political Report, NY-1 is now considered “Likely Republican,” a race that “is not considered competitive at this point” but has “the potential to become engaged.”

“This is a definitely centrist district that up until fairly recently rewarded moderation,” said Steve Israel, the former longtime Democratic congressman from Long Island, who repped the Second District, then the Third District, between 2001 and 2017. “Lee Zeldin pulled it much further to the right, but if a moderate Democrat is running against LaLota, it’s a very competitive race.” Israel said that eight months ago, he and his wife were asked to dinner by Hoovalon. They all went to the Century Club in Manhattan, and Avlon revealed his intention to run. “I said, ‘You’re crazy. You have the greatest life right now, working for CNN,’” Israel recalled, “and he said, ‘I think democracy is at the tipping point.’” Israel has been occasionally advising him on the primary since. “If the Democrats can win New York 1, they can win almost any competitive district in New York,” he said.

Democrats got a jolt of optimism in February when Tom Suozzi flipped the Third District (on the other end of Long Island), which had been held by George Santos. “I’ve spoken to Tom, and I’ve had enormous respect for the race he ran,” said Avlon. “The big takeaways are, first, candidate selection matters,” he said, and second, “too often Democrats get stuck on defense.” Suozzi ran a very centrist campaign, talking plainly about crime, gangs, and the migrant crisis.

Avlon thinks he’s in a position to mimic Suozzi’s playbook and run to the center — progressives be damned. “This is an area, where, because of my experience working for Rudy, I know crime policy, how to play off these issues,” said Avlon. “Quality of life matters, and public safety is a fundamental civil right. We shouldn’t forget that. Democrats need to share that. They’re tough on crime and tough on the causes of crime. Remember who wrote the Crime Bill back in the 1990s. It was Joe Biden, passed under Bill Clinton, with some Republican support. It wasn’t perfect, but it was effective.”

Suozzi told me that the First is “a tough district to win.” He’s spoken a bit to Avlon and thinks he is “a very good candidate. I think he’s smart and practical and he’s going to demonstrate an ability to raise money.” When I pointed out that Avlon is not from the district, Suozzi said, “That’s a challenge in any race. But it’s not insurmountable.”

Avlon’s defense when asked about being a carpetbagger is to point out that, technically, LaLota himself doesn’t live in the district. But he has always lived on Long Island. “I have true ties to the district,” LaLota told me. “I’m not faking it by buying some sort of summer home.” He added that locals can spot an outsider. “Long Islanders always reference being on Long Island, not in Long Island. And both in person and on video and in a social-media post, Avlon says in Long Island multiple times.”

Regionalisms aside, LaLota is fairly middle of the road by today’s GOP standards. It’s true that he was the very first sitting Republican in a Biden-won district to endorse Trump for 2024, but, he assured me, he isn’t an election denier and voted in favor of aid to Ukraine and Israel. “I am much more with the Speaker than Marjorie Taylor Greene on this and many other issues,” LaLota said. He also led the charge from within his own party to oust George Santos.

After doing my own homework, I grilled Avlon about how much he knew about his own district: shoreline-preservation bills, farmer aid, ferry transit lines, and even the Shinnecock Indian Nation and Montaukett Tribe. He passed my pop quiz easily, then brought it back to what he said he will campaign on: “The No. 1 issue is affordability. There’s Donald Trump, defense of democracy, and there’s affordability and abortion.” It’s not exactly as stirring as the Four Freedoms, but it might just get him elected.

And what will he do if it doesn’t? “I don’t know, figure it out,” said Hoover. “If he doesn’t win, which by the way, he might not win. I want him to win. I hope he wins. But he can’t go back to being a journalist at CNN. Like, that’s done.”