This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

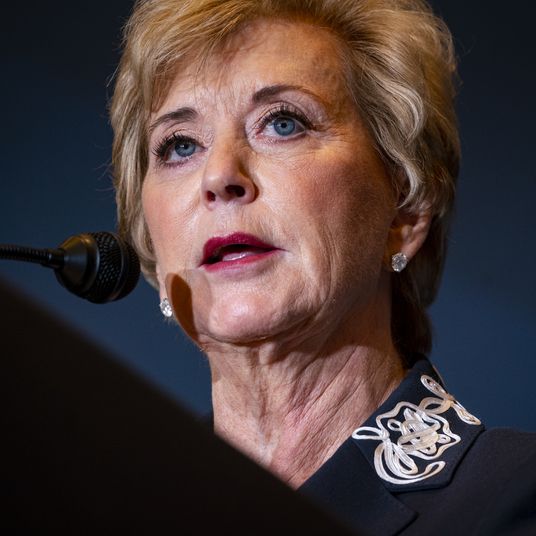

Jay-Z is pushing to get it. Nas wants a piece. The owner of the Mets is spending a fortune to win. A subsidiary of the Yankees is trying, too. Manhattan’s biggest commercial landlord is all-in. The Hudson Yards crew wants it, and so does the man behind Coney Island. A former police commissioner is wrapped up in this. And a former governor. And Eric Adams’s closest confidant. And the guy who owns Donald Trump’s old golf course. And the head of a private intelligence firm.

What they’re all after is a downstate New York casino license — “a license to print money, literally,” as one insider close to several of the bidders puts it. The state’s gaming commission is expected to award up to three permits next year. Eleven major groups are in the hunt. Two of them are considered heavy favorites, because they already operate what are known as racinos — slots operations connected to existing horse-racing tracks — and have the political support that comes with incumbency. That leaves a single, almost unfathomably lucrative license up for grabs. The winner will fork over a one-time fee of half a billion dollars and volunteer to pay tax rates approaching 70 percent. And they’ll do it. The victor of this zero-sum game will get a once-in-a-century chance to profit and remake an entire section of the city.

New Yorkers may be used to grandiosity, to shrugging at a new skyscraper like it’s another foothill in a mountain chain. The casino deal is different. The opportunity is so gargantuan that the bidders are promising, almost as add-ons, to spend billions to solve some of the city’s most challenging engineering feats and to build concert halls, apartment towers, science centers, public schools, parks, even a museum of democracy. These are projects that would ordinarily merit headlines all on their own. In this contest, they’re mere loss leaders. A license to operate a casino in or directly outside New York City is worth almost any investment. “Even one of these bids would be one of the biggest land-use battles in the history of New York, and we’ve got five right here in Manhattan,” says Mark Levine, the borough president.

The way the leading bidders look at it, the only thing between them and a perpetual river of cash is the right PR and lobbying effort. Those pressure campaigns are underway, with boldfaced public endorsements and backroom arm-twisting. At this stage in the process, each campaign is uniquely microtargeted. That’s because in addition to all the environmental and zoning reviews you’d expect, every New York City casino bid has to clear an additional hurdle. Rules set by the state say that a given proposal cannot advance unless it has the support of a “community advisory committee” specific to its location. Each committee is made up of six people appointed by the mayor, the governor, and the site’s borough president, city councilmember, state senator, and assemblymember. That gives local elected officials extraordinary leverage over the multibillion-dollar organizations that want to build in their backyards.

The bids that pass these committees will then be evaluated by a four-person casino board in Albany. Their recommendations will then go before the state gaming commission, whose members are appointed by the governor. They’re supposed to judge the bids mostly on economic criteria, favoring ones that create the most jobs, pump the most money into the state, and do so the quickest. Lesser considerations: environmental impact, diversity commitments, and any effects on the local communities.

It is either the perfect time for New York to welcome casinos or a perfectly horrendous one, depending on your point of view. The city is still shaking off the effects of the pandemic. The commercial-real-estate market is in a slow-motion crisis, and the viability of entire neighborhoods is an open question. Our mayor, who is the subject of at least three federal and state corruption investigations, does not exactly seem to have a master plan for growth. A casino could be just what New York needs. But if gambling history is any guide, an outsize portion of the money flowing into the winners’ slot machines and blackjack tables will come from the people who can least afford to give it up. The bidders like to talk about how glamorous their casinos will be and how they want to bring in out-of-town whales. In private, some of them acknowledge the reality. “The margins are in the problem gamblers, or people who aren’t wealthy at all,” says the source close to several contenders. Or, as an executive at one of the bidders told me: “The idea that you’re going to get a crowd of people in bow ties? It’s a stretch.”

Most of the people involved have come to peace with the trade-off. The taxes, the jobs, all the extra economic activity that everyone assumes will accrue — it’s just too much to pass up. “In my line of work, I have to weigh the goods and the bads,” says Donovan Richards, the borough president of Queens. “People absolutely will be hurt with a casino being in close proximity. But our jobs are to make sure that we are minimizing it as much as possible.” Richards counts himself as a casino supporter.

So who’s going to come out on top?

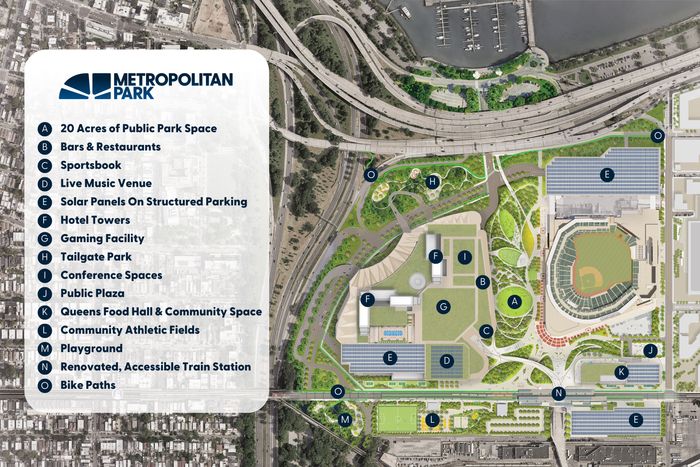

Nowhere has the campaign for a casino been more intense — and the stakes more clear — than out by Citi Field, the home of the New York Mets in Queens. The team’s owner, Steven A. Cohen, was the real-life inspiration for Billions, a wealthier-than-God investor whose hedge fund shut down after it pled guilty to violating insider-trading laws. He’s on a mission for respectability and accustomed to buying what he wants. Cohen is famous in the art world for purchasing the same Picasso twice ($155 million) and in the sports world for assembling baseball’s most expensive roster ($379 million). Those expenditures are nothing compared to his quest to transform the Citi Field area into a top-of-the-line casino and resort, with a Hard Rock Hotel, several restaurants, a concert venue on par with Radio City, a manicured new green space, and more. Cohen says he’ll rebuild the local subway station, underwrite new medical and mental-health centers, and fund the Herculean engineering work necessary to save this sinking plot from returning to Flushing Bay. Total cost: $8 billion.

To persuade local officials to get on board, Cohen and his chief of staff, Michael Sullivan, hired a battalion of fixers that includes Eric Adams’s fundraisers, Michael Bloomberg’s deputies, and Andrew Cuomo’s chief of staff. Their efforts worked. The local assemblyman and borough president have pledged their support, and so has the city councilman (though the New York Post reported he had to be threatened with a primary challenge to get in line — something Cohen’s team denies). That should ensure Cohen clears his community advisory committee. “We feel confident given the overwhelming support from elected officials, unions, and the local community that we have the best overall project. We are all-in,” says a spokesman, Karl Rickett.

But there’s a hitch. The parking lot that Cohen wants to use is technically parkland, part of the old World’s Fair grounds. To use the area for anything else, there needs to be a bill in the legislature to change that status, to “alienate” it. No bill, no casino. Albany precedent dictates that the bill comes from local representatives, and in the state senate, that’s Jessica Ramos, a 38-year-old single mother of two, a lifelong lefty activist born to undocumented Colombian immigrants, and someone who has grappled with developers for years. She has de facto veto power over Cohen’s entire project.

Cohen and Sullivan have tried just about everything to convince Ramos. They’ve tasked her former colleagues in the labor movement to lean on her and sent canvassers to knock on tens of thousands of doors in her district. Cohen’s family foundation donated $116 million to a local community college for a “workforce training center,” the largest in the City University of New York system’s history. Over almost two years of persuasion, Ramos has given indications that she’s against Cohen’s casino, but she’s never made it official or categorical, placing her support just out of reach. “Playing chess with a billionaire,” she tells me, “has been very interesting.”

We’re meeting in the Citi Field parking lot. It’s an ugly day, pissing rain, and there are no shops to duck into, just highways and bare asphalt. Ramos says she wants something new here. Everyone does. The per-capita income in Ramos’s district is less than $30,000. An underground economy is flourishing on nearby Roosevelt Avenue; the cops just busted a dozen brothels there. Ramos finds it hard to see how a casino would help. And she can’t get past Cohen’s imperiousness. “I’m resentful of him holding our entire community hostage by saying that it’s a casino or nothing,” Ramos says. “Why should anybody just get their way like that when it’s a decision that is going to impact millions of people? This is actually public land. Our land.”

People in Cohen’s orbit have long assumed that talk like this is simply a negotiating position. Sure, Ramos may have fought big development projects before. (She was vocal in her opposition to Amazon building an enormous headquarters nearby.) But who wants to keep this dump? What ambitious politician turns down this much money? This many jobs? This much attention?

What Cohen doesn’t know is that Ramos’s mind is now 100 percent made up. She’s making her formal opposition known, right here in these lines you’re reading. We cross Northern Boulevard, walking toward Flushing Bay, as the rain turns into a downpour. She knows her constituents need more resources; one out of five children is in poverty. She knows Cohen is promising them hope. But selling hope to desperate people — that’s something she recognizes as the fundamental casino business plan, one that doesn’t work out well for anyone but the casino.

She’s out. “We’re not in a place to host a casino,” Ramos says. “The people who are here, they’re hoping to build generational wealth. And I just don’t see how a casino helps us meet that goal. I mean, it’s literally the opposite. It’s the extraction of the very little wealth we have.”

Cohen’s casino bid is now all but dead, although of course his team insists they still have a chance. (“There is both time and multiple pathways to get this done,” Rickett says.) That means that some of the best-positioned competitors for the final casino license are in Manhattan. Consider the bid out of Hudson Yards. The site is already somewhat Vegas-y, in the sense it’s a synthetic, air-conditioned megadevelopment built in the middle of nowhere. Like the Bellagio, it already has a Cartier, a Fendi, and a Dior. Related Companies, which built Hudson Yards, is offering to partner with Wynn Resorts to spend a reported $12 billion to essentially double the size of the complex, starting with the construction of a $2 billion deck to cover the open rail yards between 11th and 12th Avenues. On top, Related wants to erect an 80-story skyscraper to hold a casino and 1,750 hotel rooms, a second tower with 1,500 apartments, and a third structure with 2 million square feet of office space and a school for 750 students. Plus a green area the size of Bryant Park. If the state gaming board prioritizes bids by capital investment, this is one with plenty.

One elected official calls it “an objectively strong bid with objectively serious political opposition.” The local community board recently released a public letter attacking the proposal, noting that the number of planned apartments is less than a third of the 5,700 units Related initially promised to construct at Hudson Yards in 2009. But political opposition may not be absolute. Related claims that the project will create 35,000 temporary construction jobs and another 5,000 permanent ones — all union. The firm wields so much influence that an operative working for a rival calls it a “shadow government.” They mean it as a compliment.

New York’s other obviously Vegas-like destination is, of course, Times Square. And the bid based there, from the developer SL Green, may provide the clearest indication of the scale of change that a casino could bring to New York. Both advocates and opponents of the project believe it has the potential to remake the city’s tourist mecca on an order not seen since City Hall went after its porno theaters in the 1980s and ’90s and reinvented it as a zone safe enough for an M&M flagship store.

Each side features some of the city’s heaviest hitters. SL Green, which owns more Manhattan office space than any other landlord, is pairing with Caesars on a plan to remake 1515 Broadway — Paramount’s headquarters now, and the set of Total Request Live back in the day — into a 950-room hotel and 250,000-square-foot gambling operation. Jay-Z’s Roc Nation is also attached to the project, helping sell it to community groups and providing some much-needed glamour. Bill Bratton, the two-time former police commissioner, is consulting on security and has outlined a $78 million array of networked cameras, surveillance drones, and private guards to keep the area safe. Frank Carone, the mayor’s former chief of staff and the city’s fastest-rising lobbyist, is an adviser. All told, SL Green and its partners would spend a reported $4 billion.

SL Green’s fate is intertwined with that of Times Square itself. And at the moment the neighborhood is unraveling, its Disneyfication moving in reverse. Illegal weed shops and fast-food spots have replaced flagship retail stores. Pedestrian foot traffic is still down about a quarter from pre-pandemic levels. Much of the commercial real estate is not prime, and even at the newly renovated 5 Times Square, in which SL Green is an investor, 25 of the 37 available floors are listed as entirely vacant. The biggest storefront is a Red Lobster, which is facing bankruptcy. And that’s just a sliver of SL Green’s holdings in the area — eight buildings, 5 million square feet.

It’s hard to envision any other single project that could counteract this decline. SL Green argues that a casino would begin a virtuous circle. “It’ll start to upgrade the quality of the streetscape,” a company executive says. “And then landlords will start investing in their properties again — less graffiti, cleaned up, more security. And it starts to be like an upward cycle of improving Times Square.” It’s counterintuitive, because casinos are typically designed to keep customers inside, cut off from the real world. SL Green’s idea is to turn the typical gambling resort inside out. The company says that while the casino will create a need for more than 3,000 hotel rooms and 25 restaurants, they intend to build less than a third of that and plan to send the remaining guests and diners to other establishments in the neighborhood. “What we’re trying to do here,” the executive says, “is make Times Square the casino.”

To make that work, SL Green needs buy-in from community members and the elected officials who represent them. The company has aggressively courted it for the last two years. The area’s biggest restaurants, commercial landlords, and the stage actors’ union are all on board. SL Green has offered unused office space to local nonprofits, promised to spend $12.5 million on public bathrooms, and held events in the neighborhood with Roc Nation legends like Fat Joe. Three people, including a state assemblyman, told me the company had dangled invitations to personally meet Jay-Z and Beyoncé.

Sometimes, the courting has been a bit too aggressive. In March 2023, SL Green was in discussions about supporting Project FIND, which helps out neighborhood seniors, in exchange for a casino endorsement. Mark Jennings, the group’s executive director, told me that when he mentioned that he needed to run any arrangement by his board of directors, the tone abruptly shifted. He recalls being asked: “‘What, you don’t like money?’ I mean, that was a literal comment that was said to me.” He was surprised the company’s fixers would object to something so basic. “I really felt like they were trying to buy me,” Jennings says. (SL Green denies that this incident occurred.)

Some of the most intense outreach has been to the theater community. SL Green and its partners have pledged to give away $30 million in Broadway ticket vouchers to casino customers and spend $20 million more in tickets for seniors and kids. But the Broadway League, which represents the big theater owners and producers, is opposed, leading a coalition of West Side community groups in trying to block the project. (Jennings and Project FIND ended up being part of it.) In the producers’ minds, they’re already bringing 15 million theatergoers to the neighborhood in a good year. They don’t see the extra ticket sales as particularly generous.

“We’re not naïve,” says the Shubert Organization’s Jeff Daniel over coffee at Sardi’s, the century-old producers’ haven. “It’s an opportunistic chance for them to cannibalize our current economic benefit.” He points out the window to Shubert Alley. His theater is on the left, and the entrance to the new Caesars casino would be on the right. The impression he gives is that it’s a little insulting for a casino to just park itself in the middle of an entertainment zone that his industry worked so hard to build.

Let’s be clear: A slice of the Broadway League’s members wouldn’t mind a casino at all. They just want it somewhere else. The argument is a reminder that the whole casino-siting process is almost comically hyperlocal. Some of the nonprofits in the Broadway League’s anti–SL Green coalition get money from a community fund backed by the Hudson Yards team. The two hypothetical casinos would be a mere dozen or so blocks apart. To the producers and their allies, this particular casino proposal is the economic and cultural equivalent of a nuclear reactor. Great if it works, but better if it’s not right next door.

Listen to the various bidders hyping their dreamland megaprojects long enough and you can almost forget the reality of what casinos are and to whom they appeal. Recently, on a weekday morning, I drove to one of the racinos: Resorts World New York City, which is adjacent to the Aqueduct Racetrack, just northwest of JFK Airport. The limited gaming products there — mainly slot machines and video terminals — were authorized by the state at another moment of fiscal alarm, in the weeks after 9/11. (It took several years for the machines to actually be installed in part because the head of the senate gaming committee, one Eric Adams, was credibly accused of funneling inside information to a top bidder.)

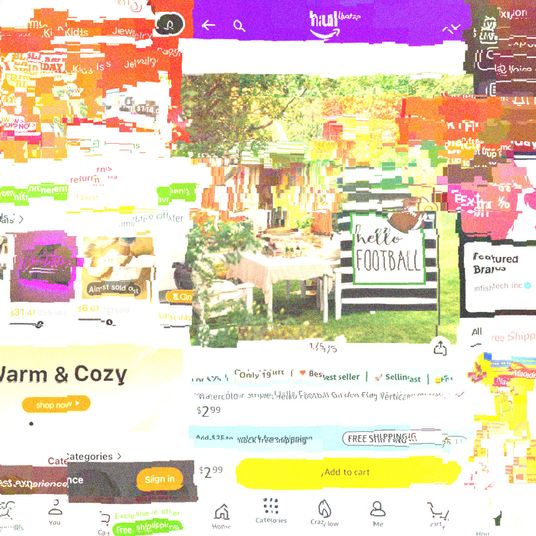

I watch an elderly woman in a walker and a mask shuffle off a shuttle bus and go inside, where white and chardonnay faux crystals hang over the gaming floor. The carpeting has an abstract cobalt-and-maize pattern out of the 1950s, perfect for absorbing a blue Curaçao margarita or last night’s Jell-O shots. A mother with a fanny pack holds her adult son by the arm; he’s having trouble walking.

Resorts World is operated by a Malaysian company, the Genting Group, and the slot machines have names like “Money Link — Egyptian Riches” and “Fu Dai Lian Lian Dragon.” Women in cocktail dresses with plunging necklines appear on screens imploring customers to join them at video blackjack tables. There are no takers, but the baccarat room is packed — 60 or so people sitting in tiny stalls and staring down at their virtual cards. Hands are $50 minimum, $4,400 max. “Lucky nines win!” a ceiling-mounted monitor proclaims. But there is no luck. The outcomes are all predetermined by a state-controlled, centralized system, just like with scratch-off lottery tickets. Nobody cheers.

It’s undeniably depressing — and jaw-droppingly lucrative. Resorts World employs 1,000 people and brings in close to $1 billion per year, making it the country’s top-grossing casino outside of Nevada. Some 68 percent of that money is given to the state, almost $700 million annually, which makes Resorts World New York’s single biggest taxpayer. The company says that if it can upgrade to a full casino license, one that allows it to offer more and different games, it will put another billion per year into the public coffers.

In all likelihood, much of that money will come from gamblers who are anything but high rollers. “The gaming market, by and large, is working folks,” says a Resorts World executive. “That’s just the North American game.” Nationwide, slots bring in more gambling revenue than sports betting, online gambling, and table games like craps and poker combined. The Encore Boston Harbor, which bills itself as a five-star resort, draws a crowd of mostly locals and gets more than half its revenue from slots.

The Encore, which is operated by Wynn, is considered a relatively strong performer among recent big-city casino projects, not all of which have proved profitable. A recent report by researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst found that the site has generated nearly 10,000 jobs and is netting the state $1 billion a year in new economic activity. But Chicago’s casino experiment has been a disaster, pulling in less than half the revenue promised. (Then there’s Atlantic City, the great-uncle of East Coast gambling, where casinos were brought in to raise a crippling 17 percent poverty rate. A half-century later, that rate is now over 32 percent.) In New York, Resorts World is one of three companies operating casinos upstate, and none of them have hit the revenue projections they initially promised. Several have renegotiated with the state to substantially cut their tax rates. One source with deep gaming-industry connections shrugs at the discrepancy: “That’s how you get projects done, right? You inflate the job prospects, you inflate the revenue.”

But there’s no denying the power of incumbency. Resorts World and the other New York–area racino — MGM Empire City in Yonkers — are deeply integrated into their communities after more than a decade of operations. Speed to market is one of the big criteria for the state gaming board, and, obviously, it’s easier to move fast when the casino’s already built. In addition, Resorts World has pledged to spend $5 billion upgrading and adding a hotel, restaurants, the grounds, a concert venue, and something it’s touting as an “innovation center.” The employee rolls would swell to 5,000. Nas, famously a son of Queens, is publicly backing the bid, along with the former point guard Kenny Smith and the TV chef Marcus Samuelsson. So are the local pols. “For an elected official,” says State Senator Joe Addabbo, “it’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Several bids are ambitious, impressive, well funded, and — given what they’re up against — widely expected to come up short. For example, the Hudson’s Bay Company wants to convert the top three floors of the Saks Fifth Avenue building into a glitzy, boutique casino. It’s maybe too much of a boutique: There wouldn’t be the enormous number of construction or hospitality jobs required by the other sites nor the floor space for slots, so the state would presumably get far less revenue. Plus, Saks is directly across East 50th Street from St. Patrick’s Cathedral. In the eyes of local elected officials and the gaming board in Albany, that’s probably not ideal.

On the other side of Manhattan, Larry Silverstein is pushing two 46-story, skybridge-linked skyscrapers. But since announcing his plans in June 2023, the project hasn’t generated much momentum. Out on Coney Island, a bid from Thor Equities would put a casino, hotel, and roller coaster by the boardwalk. It’s up against the unavoidable optics of seeming like just another Atlantic City.

Then there’s the plan in Midtown East. It first got attention with a rendering that showed a gigantic Ferris wheel next door to (and nearly the size of) the United Nations, the centerpiece of a resort with a 1,200-room hotel, two towers of apartment buildings, and four acres of park. Big fortunes will attract over-the-top ideas, sometimes even a bit of magical thinking, but this seemed like something out of a Bond movie or maybe Austin Powers. The entrepreneur behind it is certainly colorful enough. Stefan Soloviev, who inherited his father Sheldon Solow’s multibillion-dollar real-estate portfolio, is nearly 50 years old but dresses like a 16-year-old skater. He has at least 20 children. (“The number isn’t important,” he once told Business Insider.) He is the 26th-biggest landowner in the United States, and his holdings include the Colorado Pacific Railroad, a 5,000-head cattle ranch in New Mexico, and a rhodium mine in Nevada. For 17 years, his family has been sitting on the largest plot of undeveloped land in Manhattan — six and a half acres along the East River. He’s wanted to build something there; the casino opportunity has him thinking mega.

Soloviev has delegated oversight of the casino to Michael Hershman, a longtime family adviser. He keeps an office at 9 West 57th Street, the sloping skyscraper that is the headquarters of Soloviev’s empire, with an appointment-only gallery of Giacomettis and Calders in the lobby. Hershman, 78, greets me on the 30th floor, before a king-of-the-world view of Central Park, and emphasizes that his bid has changed to be more subtle. Five hundred affordable-housing units are in, the Ferris wheel is out, and the casino itself is underground.“You’re not even gonna know it’s there,” he says. Other elements include a 35,000-square-foot wellness center and a Museum of Freedom and Democracy complete with pieces of the Berlin Wall.

Hershman says he’s met with the U.N. and assured them that a casino would not pose a security concern. “My background is intelligence,” he says. He adds that he and a consultancy he runs have “been involved in investigations that have brought down, I think, five world leaders,” including Ferdinand Marcos, Rajiv Gandhi, and Richard Nixon. The real-estate trade publication The Real Deal once Photoshopped him in a trench coat and holding a magnifying glass for a profile, noting that he “took a bullet infiltrating the Palestine Liberation Organization.” He’s a co-founder of the anticorruption outfit Transparency International; in a few days, he’s scheduled to give an award to Russian dissident Alexei Navalny’s daughter.

Other developers think Soloviev and Hershman have zero shot, in large part because they are not signing up the political hired guns that every other bidder views as essential. Both Cohen and Resorts World have enlisted the lobbying shop Moonshot Strategies, which raised $7 million for Adams’s 2021 campaign. Tim Pearson, the mayor’s scandal-scarred friend and aide, was for a time getting paid by Resorts World while he was also on a City Hall salary. Vito Pitta, who heads Adams’s legal-defense fund, has a lobbying firm that works for Bally’s, which is trying to build a casino on Donald Trump’s old golf course in the Bronx. Neal Kwatra, the former political director of the powerful hotel trade union, is working for both Bally’s and Resorts World. Nassau County Executive Bruce Blakeman has acted as an unpaid spokesperson for the Las Vegas Sands Corporation’s bid to put a casino at the Coliseum there, while former governor David Paterson is literally on the payroll.

“Dude, I’m strange,” Hershman says, leaning forward. “We don’t make political contributions. I’m going to win this fucker on merit, and if I don’t win it on merit, I’ll be able to sleep well at night. Now, am I being naïve? Being a New Yorker, I know how New York works. But I’m not going to play the game. Not going to do it.”

Besides, Hershman has a backup plan. While he — like all of the big bidders — insists that the casino has to be the “economic engine” that powers their wildly ambitious developments, it’s only true up to a point. Hershman and Soloviev already have approval to build three residential towers, an office building, and a slightly smaller park on the site. Hershman says that if they don’t win the casino, he’d need tax breaks to build the affordable units. But the towers would still go up.

Before Jessica Ramos and Steve Cohen squared off over his casino plan, they had the beginnings of a working relationship. After Cohen bought the Mets, he invested in the working-class neighborhoods surrounding the stadium. And Ramos brokered a first-of-its-kind meeting between Cohen and advocates for minor-league ballplayers that led to their salaries being doubled. In a statement, she thanked “Uncle Steve” for his help.

Early in the casino planning, Cohen’s deputy, Sullivan, asked Ramos what she’d need to get behind the project. She said that all the new jobs had to be union; that undocumented workers needed accommodation; and that any agreement had to be binding, because developers had an ugly track record of making community-benefit pledges and then ignoring them. Sullivan seemed open to the ideas. But Ramos warned him: Don’t try to force this on us. Big campaigns by powerful outsiders had a habit of dying in Queens.

Yet Cohen and Sullivan took an aggressive tack. They hosted 16 “visioning sessions” and community workshops at the ballpark. Casino-friendly mailers blanketed Queens; the return address was an empty storefront in Corona with a work permit on the front door. Sullivan irritated Ramos by making appearances across the area, handing out turkey at a food pantry in Corona and appearing at the head of a Lunar New Year parade right next to the mayor and the governor. Where many might have seen neighborliness, Ramos and other elected officials saw Sullivan almost as a politician running against them. It also irked Ramos when Sullivan, in his seeming attempt to hire every local influence peddler he could find, brought on a few whom she’d clashed with in the past. The strategy of persuading Ramos seemed to shift to one of pushing her. One insider who witnessed the dynamic says, “Sully kept saying, ‘I’m gonna box her in.’ All you have to do is meet her one time to know that’s the dumbest thing to do.”

The moment Ramos became convinced that Sullivan was no longer interested in persuasion happened one day in February. She was hosting her third town hall on the casino at the Queens Hall of Science. Sullivan staged a big press conference next door, touting all the Cohen plan’s sweeteners: a train-station upgrade, a “Taste of Queens” food hall, a $163 million community fund. More than 100 members of the pro-casino painters union were outside. At the town hall, one of Sullivan’s consultants passed out handwritten signs: “More Live Music!” “This Sounds Fun!” “Queremos el Food Hall.” During the Q&A session, the first eight people to step up to the mic all seemed to be in Cohen and Sullivan’s corner. (Two later posted selfies with Sullivan at Citi Field on the Mets’ opening day.) To Ramos, it all felt like astroturf and ambush.

Ramos knows she’s about to get major blowback for her decision to formally oppose the casino. It’s why she felt like she couldn’t say anything definitive in public for months, not while the state legislature was still in session. If she had, Cohen and Sullivan might have tried to get a different senator to introduce the park alienation bill, even though that would have been an almost unthinkable breach of protocol. “I’ve been trying to shorten their window for them to be able to go around me,” she says in the Citi Field parking lot. “You see, I have had to be very deliberate in my gestures.”

It’s been a strain. She’s had casino advocates confront her on the street while she’s picking up her kids and anti-casino protesters show up at her house with bullhorns and banners. Ramos starts tearing up. “I know that saying ‘yes’ is easy. I know that saying ‘no’ is hard,” she says. She balls up her hands in fists. “My neighbors work their butts off every fucking day. We deserve the best. And we are constantly shortchanged at every level of government. We’ve been desperate for economic development here. And our greatest hope is a fucking casino?!”

She’s hoping to offer a compromise bill, one that can turn the Citi Field parking lot into a convention center and hotel, maybe along with a concert venue and food hall. As we walk back toward the 7 train, Ramos and I talk about a poll she recently released, one that included a question about whether there should be two casinos in Queens. Hold on. Does that mean she’s okay with a full license going to the Resorts World operation at the Aqueduct? After all those warnings about casinos leaching money out of the local community, she’s cool with one being just a few miles down I-678? One that’s so transparently miserable?

Ramos doesn’t answer directly. The Aqueduct isn’t in her district, and she offers a Colombian idiom: No tengo velas en ese entierro. I don’t have candles at that funeral. It’s not my fight. Then she says, “As someone who doesn’t gamble and doesn’t want to see more people gamble, it does kind of make sense for the two existing casinos to be full casinos. Right?” She’s done her part to change this round of the game. But every gambler knows who wins in the end.