As Election Day approaches, with the possibility of a Trump restoration looking increasingly likely — or at least not unlikely — the mainstream press, which in its telling stood up so bravely against his lies and corruption last time, is very worried that it might not have all that in it again.

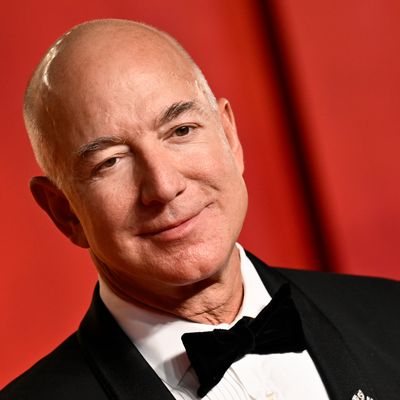

Sure, some people are fired up. But underlying it is a mix of exhaustion, frustration, and fear. After the so-called subscriptions “Trump Bump” that came thanks to readers deciding to actually pay for their news out of fear that, as the Washington Post declared, “Democracy Dies in Darkness,” the journalism business hasn’t really gotten any better. An endless series of exposés hammered home the dangers to civil liberties and possibly even press freedoms that Trump presented — and quite openly declared — but didn’t seem to do much to disqualify him to the half of the country that gets news from sources more amenable to the MAGA point of view. Or were just too exhausted themselves to pay much attention. Then, last week, Jeff Bezos, who’d so assiduously propped up the Washington Post for the last decade, suggested he might want to do things differently this time around. And, as NPR reported and the Post’s own media reporter later confirmed, over 250,000 digital subscribers — 10 percent of the paper’s base — responded by canceling. Among other things, it’s a shocking illustration of how dependent the press is on its readers’ goodwill.

Call it the Bezos Ditch, the ultimate antidote to the Trump Bump.

On Monday, on the fourth floor of the Washington Post’s K Street headquarters, editorial-page editor David Shipley addressed a weary staff. A few dozen members of the opinion operation gathered to hear from Shipley following last Friday’s news that the paper would end its decades-long practice of presidential endorsements — but not other political endorsements — a decision made by Bezos and announced by publisher Will Lewis. Shipley explained that the paper’s billionaire owner had started expressing concerns about running endorsement editorials in general about four weeks earlier, and the ultimate decision came despite Shipley’s “strenuous efforts” to change Bezos’s mind, according to a Post staffer present. It also came after the Post’s editorial board had reportedly drafted an endorsement of Kamala Harris, though Lewis later insisted that Bezos made the decision before reading any such draft.

“I think everybody is trying to just take a few weeks and see where the numbers all come out,” executive editor Matt Murray told the newsroom at a meeting on Tuesday, per a Post staffer. “The deed is done. I can’t undo the deed,” Murray said of Bezos’s decision. In the sidebar Zoom chat of the meeting, a reporter asked what to do with all of the people complaining to them — should they tell them to write letters to the editor? “Please don’t,” a letters editor responded, adding that they’d received 15,000 emails in 24 hours.

Murray’s comments came after Bezos wrote an opinion piece on Monday evening titled “The hard truth: Americans don’t trust the news media,” in which he defended his decision. “Presidential endorsements do nothing to tip the scales of an election” and only “create a perception of bias” and “non-independence,” he wrote. “We must work harder to control what we can control to increase our credibility.”

Many reporters I spoke to at the Post and beyond agree: Political endorsements make it harder for them to do their jobs given that most readers don’t understand newsrooms are independent of the opinion department. But Bezos’s 11th-hour decision has ironically catapulted the question of the Post’s independence into the spotlight, as Amazon and Blue Origin — both founded by Bezos — compete for government contracts, and Trump, a frequent critic of the Post, has gotten in the way of Bezos’s business interests before. Bezos in his opinion piece said “no quid pro quo of any kind is at work here” and that he was unaware Blue Origin executives would be meeting with Trump on the day of the announcement. “I sighed when I found out, because I knew it would provide ammunition to those who would like to frame this as anything other than a principled decision,” Bezos wrote. He chalked the lateness of the decision up to “inadequate planning.”

“Nobody’s surprised an election was coming up,” former Post executive editor Marty Baron told me Monday evening. In his eight years leading the Post — beginning in 2013, just a few months before Bezos bought the paper — Baron returned the paper to its former glory, particularly with aggressive coverage of the Trump administration. “And the circumstances do raise serious questions about what’s the motivation here,” Baron said, noting Bezos supported presidential endorsements in 2016 and 2020. “Why he’s had a change of heart, I don’t know. But he does have these other interests, and it’s very difficult to avoid the conclusion that these other interests influence his thinking about whether they should run editorials or not, particularly when this decision is made in the final weeks of an election.” Bezos, as Baron notes, was the one who selected “Democracy Dies in Darkness” to be the Post’s mission statement in 2017. “The feeling, I think, among a lot of people — particularly subscribers who canceled, unfortunately,” said Baron, is “that the mission’s been abandoned.”

But this is part of a larger problem. Everybody did great work last time around. But to what end? Efforts to limit Trump’s reach in the past have, one TV executive argues, blown up in the mainstream media’s face. “The left-wing attempt to deplatform Trump after the 2020 election was the single biggest mistake because it forced him to create his own alternative-reality ecosystem,” they said, “and it only accelerated our own irrelevance.”

This was part of Bezos’s point, of course, however clumsily and belatedly made. The Post’s decision came in the wake of the Los Angeles Times, also owned by a billionaire, Patrick Soon-Shiong, announcing that it too would demur on endorsing a presidential candidate this time. Soon-Shiong’s reasoning was not unlike Bezos’s: an attempt to reclaim some mantle of evenhandedness for the paper. Many found it difficult to not read something into that timing as well. Soon-Shiong too has business interests dependent on the government’s good will. Still, it could be something more particular to that owner’s family dynamic. Soon-Shiong’s daughter, Nika, said that the decision not to endorse stemmed from Harris’s stance on the Gaza war, a statement her father then contradicted. “If you’re an L.A. Times reader and consumer, you’re left uncertain what to believe,” said one former editor. As a result, the L.A. Times, too, has seen resignations, including that of editorials editor Mariel Garza, and fleeing subscribers — more than 18,000 in the week following the decision, according to Semafor.

Endorsements are among a series of concerns gripping newsrooms as they brace for the potential reelection of a president who declared the press the “enemy of the people” and has vowed retribution against the media in a second term — threatening, on the campaign trail and in interviews, to throw reporters in jail and revoke television networks’ broadcast licenses. While some executives feel it’s too early to work through questions about how to approach a second Trump term, it is top of mind for reporters with experience covering him.

“Many of us lived through 1.0, and we were chasing tweets at 11:30 at night, breathlessly trying to report out what he was saying and thinking based largely on Twitter, only to sometimes find that it didn’t really mean anything,” said one. “A lot of good reporting did get behind the curtain last time, but there was so much noise that it was hard to carve out the time and journalistic discipline to go deeper.” And while the endless outrage cycle of Trump was, last time around, good business, this reporter expects that, in a potential 2.0, “the noise is what news consumers — even dedicated ones — will turn off.” Added a second TV executive: “There’s a huge amount of anxiety over whether, if he wins, people just put their head in the sand for four years and wait it out. The interviews that have happened this year have been fine; they haven’t been ‘holy shit’ numbers. My sense is if he wins, it’ll be more news avoidance than Trump Bump.”

“I think if people want total clarity in how to cover Donald Trump, there is no total clarity. You have to do it with a mix of deep reporting and actually covering what he says,” former New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet, who led the newsroom from 2014 to 2022, told me. “If Donald Trump as president does the things he says he wants to do, the press is going to be really relevant. And, frankly, only a handful of news organizations are going to be able to cover it aggressively, no matter how much anybody thinks that there are 20 news organizations that can. There are not,” said Baquet. “There are a handful that are out in the world that can cover foreign policy while at the same time covering the White House and Congress aggressively. And people may criticize those news organizations, but you can count ’em on one hand.”

Given things Trump has said he would do, a second political reporter supposes that, if Trump wins, outlets’ investigative teams might essentially become extensions of their politics unit. “If he is trying to turn America into an autocracy, could [investigative reporters] embark on a series about sexism in girls sports? Could that be what they use their considerable firepower for?” they asked. “Maybe, but I think if there’s actual things to investigate with a president, it would be hard to use those sorts of resources for much other than that.”

And resources this time are in shorter supply, which may hamper news organizations’ ability to fact-check Trump at every turn as they did in 2017. “There is growing concern in many newsrooms about how executives are going to handle a potential Trump presidency with the fall of local news, the fall of advertising revenue. It all could suggest that executives might feel they’re operating from a position of weakness rather than strength as they deal with any new administration,” said one veteran reporter.

“I wish I could tell you there was a single newsroom head that I thought was looking out for journalism first, and of the five major orgs, there’s not one. We have a bunch of people afraid of losing their own jobs,” said the first TV executive. “They’re all looking at bottom-line issues and trying to figure out how to cater to Trump. There are individual newsroom leaders at shows that are worried about these things, but there is nobody in charge ready to speak up, and certainly no deputies in charge willing to either. They’re all just trying to prepare for massive cuts, and that’s what’s coming either way.”

“It’s going to change everything if he wins,” said the second TV executive. “You’ve got the major disruptions underpinning everything — strategically, platform-wise, consumer technology — no matter what happens in the election. And then if Trump wins, all of a sudden you’ve got this other pressure on everything. There’s brand damage. He undermines trust in the media. It’s just going to add a level of complexity.”

And then there’s the question of general fatigue among reporters who have done this work for the better part of a decade. “Can they summon the energy and the shock of the news to cover this thing, or do you need to bring in reinforcements — people for whom it is really brand-new again?” asked one top editor at a major news publication. A third political reporter said they’re surprised to see that many of their peers are ready to redeploy for Trump duty. But as another put it, despite the grueling nature of the gig, “I think it would be hard to live in the U.S. and work at a newspaper and be sourced in that world and know that world and decide I’m just not going to cover the biggest story in the world right now.”

Some see Bezos’s last-minute endorsement decision as a portent of his waning support for the newsroom. But others are reserving judgment until evidence suggests otherwise. “I’m furious because the timing is dumb and it has put us in a horrific situation, but the idea that Bezos is saying we shouldn’t endorse is potentially fine,” one longtime Post reporter said. “The way I’d feel he didn’t have my back is if he started weighing in on the news side, saying he didn’t like a story we wrote about holding power — be that Trump or Harris — to account. But if he ever meddled in the news side, you would have mass resignations, on the spot, from the top on down.”

Ominous comparisons to what has happened to the press in places like Russia, Turkey, Hong Kong, or Hungary aside, the big question is, as one of the TV execs put it, “If half the country has decided that Trump is qualified to be president, that means they’re not reading any of this media, and we’ve lost this audience completely. A Trump victory means mainstream media is dead in its current form. And the question is what does it look like after.”