This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

A little after 3 a.m. on October 29, one week before the election, Steve Bannon walked out the gates of FCI Danbury, a low-security federal prison in Connecticut. He was wearing the only personal clothes he had: his workout outfit, a baggy gray sweat suit. He carried a few plastic bags jammed with papers and some commissary items he was keeping as reminders: a bowl, a spoon, a plastic coffee mug. For four eventful months, Bannon — a man of constant chaotic action — had been penned up as he served a sentence for contempt of Congress. Bannon’s daughter Maureen, who had run his multi-platform media company in his absence, had come to greet him. She threw her arms open wide outside the prison’s razor-wired fence. Later that morning, she would post a photo of their reunion to X along with the message “LET’S FUCKING GO!!!!”

That afternoon at a packed press conference at the Loews Regency on Park Avenue, Bannon declared, “Victory is at hand.” Twenty pounds lighter than when he went inside, he was in his old uniform — multilayered black shirts, cargo pants, leather boots, Barbour jacket — and back to his old bluster. “I think you can see today that I am far from broken,” he said. “I have been empowered.” Behind him stood a pair of bodyguards and an extremist welcoming committee.

(Notables in attendance included Raheem Kassam, a British right-wing media figure; Naomi Wolf, the feminist turned anti-vaxx polemicist; and Erik Prince, the mercenary-company founder.) Bannon was delighted to entertain questions from the press. He said he was in the best shape of his life and thoroughly unreformed.

Had he talked to Donald Trump? “We’ve had a chat,” he said. Were they up for a repeat of January 6? “We believe in the American system of democracy,” Bannon replied, “and the reason we like democracy is we’re winning.”

Since guiding the once-and-future president’s first campaign in 2016, Bannon’s personal proximity to Trump had fluctuated wildly, swinging through periods of expulsion and reacceptance. What had remained constant was his centrality to the populist movement that had powered Trump’s ascent, then his return from defeat, indictments, and political exile. As host of War Room, a news talk show that ranked among the nation’s most popular political podcasts before he went to prison, Bannon had poured accelerants on Trump’s fires, spreading his conspiracy theories about the 2020 election and helping to rally Trump’s mob. (His contempt sentence was related to his refusal to respond to a subpoena from the congressional committee investigating January 6.) Over the next four years of opposition, Bannon had acted as a rebel ideologue, promoting destabilizing ideas — impeaching President Joe Biden (unsuccessful), toppling House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (successful) — and providing a platform for his party’s hardest hard-liners. He says he offered Trump direct advice on occasion during the campaign and will continue to do so if asked during his second term, but his more tangible influence came through the ideas he amplified. The voices Bannon put on War Room — Trump loyalists like his legal adviser Boris Epshteyn, national-security bomb-thrower Kash Patel, and then-Congressman Matt Gaetz, a frequent guest and occasional fill-in host — were key figures of the campaign and the government-in-waiting. Bannon’s enemies were Trump’s own.

“If you look at the show,” Bannon would later tell me, “we’re always months ahead of where the campaign and the president are going to go.” After his release, he called himself a “political prisoner” and said Trump’s most important task, after winning the election, would be to reckon with the Justice Department and the prosecutors who had tried to convict a former president of crimes. The day Bannon reported to prison this past July, Trump said the Democrats had “opened up a Pandora’s box.” Now, with victory, Bannon expected all the demons to come out.

For Election Week, Bannon threw himself right back into War Room, doing two-hour shows in the morning and afternoon. The day after his release, I returned to the Loews Regency, where Bannon had set up a remote studio in his suite. The show had continued in his absence with a roster of guest hosts, but its audience numbers had fallen sharply. (By mid-November, War Room would leap back in Apple’s top-20 news podcasts, according to the analytics firm Podtrac.) Bannon said he was more concerned, though, about the state of Trump’s turnout operation. Since Kamala Harris had taken over the Democratic ticket — a messaging and momentum shift he had been forced to watch mutely from Danbury — she had raised a billion dollars. Her campaign had hired 2,500 workers and opened 358 local offices, enabling it to deploy an army of tens of thousands of door-knockers. By contrast, the Trump ground operation appeared nonexistent. “The only thing that matters is we have to bring off a mass mobilization in 96 hours,” Bannon said, “and nobody’s doing the fucking work.”

Bannon likes to say War Room speaks to “the cadre, the activist grassroots base” — the volunteers who do the grunt work of campaigning. For the previous four years, Bannon had been preaching to them, advocating a “precinct strategy” to rebuild the Republican Party from the ground up in Trump’s image. “Steve is the one who started yelling after 2020 that this can never happen again,” Caroline Wren, a frequent War Room guest, told me shortly after I saw Bannon in his suite, as she sipped a glass of white wine in the lobby bar.

Wren was listed as an organizer on National Park Service permits for Trump’s speech at the Ellipse on January 6. After that failure to stop the transfer of power, Wren said people like Bannon had concluded that “we can’t rely on any of the party committees and the Establishment consulting class. We are going to have to do this ourselves. Which is when he started activating the War Room posse.” An adviser to then–Senate candidate Kari Lake, Wren had just appeared on War Room to bring news from Arizona, where she said the local party machinery was dominated by “the types of people who view the election as life and death.”

The Democrats were running the same type of data-driven turnout effort they had been employing since the Obama era. Trump had largely delegated his ground operation to activists, podcasters, and Elon Musk, who was throwing a reported $200 million around the swing states through a super-PAC. Bannon had a history of antagonism with Musk, whom he saw as a China-dependent billionaire defense contractor. In 2023, he accused him of being “owned — lock, stock, and barrel — by the Chinese Communist Party.” (Musk tweeted in reply that he had once considered Bannon “smart & evil” but now realized he was “wrong about the first part.”) A year later, they were both on the same team, but Bannon was still skeptical of Musk’s motives and figured he was squandering his money. “What I hear is that they’ve lifted a hundred million of the 200,” he said. “Let’s just hope a hundred million is on target.”

Bannon placed greater faith in his own tribe. He hates being called a podcaster because he feels it’s diminishing. (Although War Room was kicked off YouTube after January 6, it can be watched as a live TV show on its own website and alternative platforms like Rumble.) But it was the podcasters who were driving this election. Trump’s campaign strategy revolved around turning out “low-propensity voters” — a phrase that Bannon and others repeated like a mantra during Election Week. The theory, which seemed very debatable at the time, was that there were millions of Americans — primarily young people and working-class men — who had checked out of the system but who might vote this time for Trump, if they could be reached and motivated. “You, the audience, are the prime movers,” Bannon said on War Room on the Sunday morning before the election, urging his followers to text their friends and hit the streets.

Bannon had broken camp at the Regency, returning to Washington, D.C., to anchor a “mass-mobilization weekend” from his home studio. He gathered reports from Patel, who streamed live from the parking lot of the Limerick Diner in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, and Epshteyn, who called in from Trump’s campaign motorcade. Bill McGinley — soon to be named Trump’s White House counsel — came on to talk about “election integrity” and poll monitoring. Bannon chatted with Charlie Kirk, another podcaster who was coordinating Trump’s turnout operation for young voters. (Bannon and Kirk are both aired on a network called Real America’s Voice.) On Saturday morning, Jack Posobiec, the author of a book suggesting the July assassination attempt on Trump was a “deep state” hit, talked live from the tailgating scene outside a Penn State football game. “The frats are 100 percent for Trump,” Posobiec said. “All the brothers.”

By Monday morning, when I joined Bannon in Washington, there was evidence the strategy was working. “The hard math is in now. They’re 700,000 votes short,” Bannon told me the morning before the election, citing the early vote in Pennsylvania. He had long talked about breaking the Democratic coalition by fomenting a working-class revolt, and with this election, it appeared as if his theoretical realignment might be coming to pass.

“Oh, man,” Bannon said as he prepared to go on the air. “I’m getting wood!”

Bannon famously resides in a redbrick townhouse a block from the Supreme Court that he ostentatiously refers to as his “embassy.” War Room’s studio space, which occupies the ground floor, is strewn with nonfiction books, stacked newspapers, political mementos, and pieces of paper covered with circled words and scrawled arrows. In the den, there’s a bust of Julius Caesar on a table behind the couch and a bust of Steve Bannon on a table below the TV. Bannon does his show from a long wooden table in the dining room, sitting in front of a fireplace mantel crammed with Catholic icons and a sign that reads THERE ARE NO CONSPIRACIES, BUT THERE ARE NO COINCIDENCES. Bannon punctuated his segments with paid pitches for sponsors that sell gold, health food, and survivalist prep kits. Mike Lindell, the MyPillow guy, called in from the campaign trail to peddle linens and praise Trump.

“It’s you — your work over the last four years has shifted the makeup of the actual electorate itself,” Bannon told his listeners that morning. He said his time in prison had given him new insight, convincing him that Trump’s appeal now extended beyond his movement’s white core. “What I do know is that Hispanic and African American men to a large extent detest her,” he said of Harris. “They’re not turning out. You see this in the numbers in Philadelphia.”

“Danbury was an awakening for me,” Bannon told me after he finished Monday’s morning show. He said everything about prison was designed to make you feel uncomfortable. There was no privacy. There were no chairs, no place for a 70-year-old man to sit down for a minute besides his bunk. Many of the inmates were on a synthetic form of marijuana called K2, he said, which made them “do outrageous things.” You had to submit to a cavity search before you could see visitors, so Bannon decided he didn’t want any. He hardly ever made phone calls, either. What he knew about the outside world came from a common television, which was always tuned to Fox News — another inconvenience for Bannon, who prefers to keep tabs on the opposition on MSNBC. His staff cut-and-pasted articles into emails he could receive through a monitored prison network and sent him daily digests of the show. But mostly he interacted with other inmates. He bunked with a group from the New York area, many of whom were doing time for financial fraud or were involved with organized crime. (“I found the Italians fascinating,” he said.) He taught a civics class. “Think about the irony of that,” he said. “‘Oh, you’re an insurrectionist.’ But I’m teaching civics, and the crew couldn’t get enough there.”

Many of Bannon’s students were minority men who had been convicted of drug crimes. He said he came to understand the pain of mass incarceration and the wisdom of the First Step Act, the sentencing-reform law that Trump had signed in his first term. Bannon said of his fellow inmates, “Half are Trump-MAGA guys. They love his style, right? One might say it’s gangster.”

Bannon could have avoided the whole unpleasant experience if he had just complied with the January 6 committee’s subpoena. But he said other prisoners respected him because he wasn’t a rat, like “that pussy” Michael Cohen, and he described his contempt as an act of defiance against the Democratic “weaponization” of the Justice Department. “If you’re not prepared to go to prison, you’re not really in this fight,” Bannon said.

He and Trump were not Mar-a-Lago pals or golf buddies. Bannon saw, in Trump, a perfect vehicle, and Trump seemed to value Bannon as a useful instrument when he needed him. Trump had fired him from his top White House role in 2017 and afterward had suggested that Bannon had “not only lost his job, he lost his mind.” But Bannon had been pulled back into Trump’s orbit after he started War Room to defend him during the Ukraine impeachment. (Jason Miller, a partner in launching the show, went on to become a top Trump campaign adviser.) After the assault on the U.S. Capitol, Bannon had never wavered in his public support of Trump or accepted Biden’s victory. Where others flipped, he had gone so far as to take a criminal charge in order to impede the January 6 investigators, and Trump appeared to appreciate the gesture. But like many others seeking to influence Trump, he had found it most effective to talk to him through a screen.

Bannon said he knew Trump was informed of what he was saying on the show through clips prepared for him by aides. “The only fight I got in with Trump was right before I went in,” he said. Bannon said he had privately urged Trump not to go through with the June debate with Biden. “I said, ‘Listen, if you defeat him, like you will defeat him, they’ll change him out.’” Like many of Bannon’s tales of prophecy, this one is hard to check; at any rate, Trump did his own thing. Bannon had also predicted, continually, that if the Democrats won in November, they would both lose their freedom. On that, Trump didn’t disagree.

“We’re in a war,” Bannon said. “We’re in a political war.” Just how literal he might be willing to make the metaphor was open to interpretation. He was preparing his audience for the possibility of another election like 2020, in which Trump would fight long past Election Day. “It doesn’t end there,” Bannon said on War Room shortly after his release. “It begins there.” When asked if he thought violence was coming, he said it was already here. He had long thought it likely that someone would try to assassinate Trump, then attempts had happened twice while he was in Danbury. “We’re in very dangerous times,” Bannon said. Even if Trump defeated Harris decisively, Bannon expected that Washington’s permanent powers — the intelligence agencies and the rest of the bureaucratic entity that he and Trump called the “deep state” — would remain resistant to his elected authority until they were crushed. “Tuesday is not going to solve anything,” Bannon said. “There’s not going to be any surrender document.”

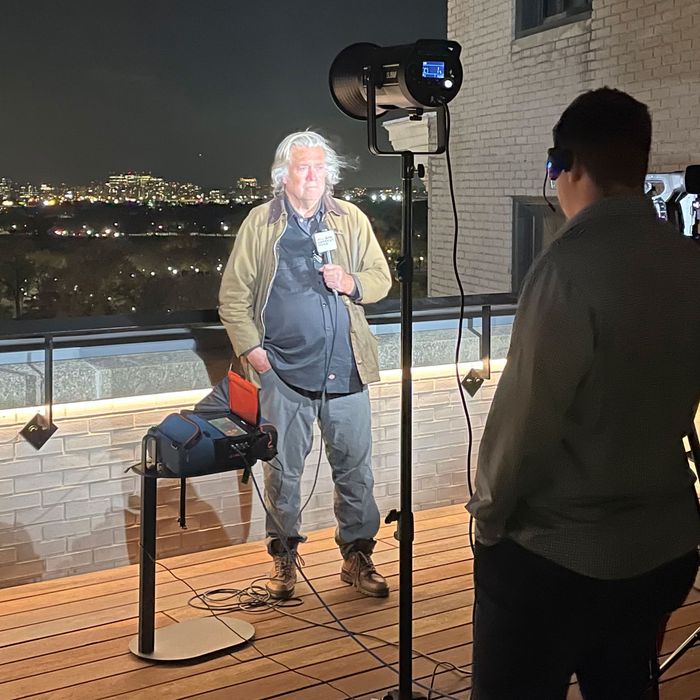

If Bannon had his way, a lot of Democrats, Republican turncoats, and denizens of the deep state would be headed to places like Danbury. Those on his target list included President Biden, Hunter Biden, Attorney General Merrick Garland, January 6 prosecutor Jack Smith, Liz Cheney, Nancy Pelosi, New York attorney general Tish James, and Manhattan DA Alvin Bragg. Bannon had made plans to do his Election Night War Room broadcast from the roof of the Willard Hotel, which had served as a command center for him and other “Stop the Steal” protest leaders in the days before January 6. The January 6 committee and Smith’s investigators had focused intensely on the Willard meetings. Going back there was Bannon’s way of saying, in case there was any doubt, he wasn’t sorry.

On Election Day, Bannon showed up to the Willard in the afternoon to set up the broadcast. He was soon joined by a zoomer contributor to War Room, Natalie Winters, who had flown up from Palm Beach. Winters is a sunny blonde 23-year-old with a gift for delivering fluent rants — Bannon’s word — about Democratic “asymmetrical warfare” and an incipient “color revolution.” For years, Bannon has played a Falstaff role on the right, surrounding himself with an ever-changing band of youngsters. His show’s producers, a pair of polite young men in fashionable footwear — one of them an NYU student who was taking time off to help — were rushing between a makeshift control room set up in a suite called the Monument Lounge and an anchor’s desk on a balcony overlooking the Mall.

“Guys, this is the Ellipse,” Bannon said, pointing out to his staffers the site of Trump’s notorious speech from the balcony. “Jack Smith, suck on that.”

A producer announced, “You got Boris.” It was Epshteyn, calling the show from Mar-a-Lago. In walked John Solomon, a conservative journalist who played a peripheral part in the events surrounding the Ukraine impeachment. He joined Bannon at the desk to provide Election Night analysis along with Winters, who was there to troll the libs.

“We’re reelecting the patriarchy,” she said with a grin with 30 seconds to air.

“From Handmaid’s Tale,” Bannon replied, “Natalie Winters.”

Showtime. “We’re here from the rooftop of the Willard Hotel, here in Washington, D.C., the imperial capital,” Bannon said into War Room’s camera. He was standing at the anchor’s desk in front of two cell phones and a stack of notebooks with three ballpoint pens clipped into the front of his top black shirt. The wind lightly mussed his mane of steely-gray hair. As he waited for the results, Bannon went to Charlie Kirk in Arizona to pore over the first exit polls, which showed a depressed turnout in liberal bastions and an electorate in a foul mood. “You’re seeing the collapse of the traditional coalition of the Democratic Party,” Bannon said. “And you’re seeing the beginning of, and the ascendancy of, a new coalition around this populist nationalist group called MAGA.”

The news kept getting better. At 8:30 p.m., Harris was up only a point in Virginia. Bannon was worried about North Carolina but then the networks called it for Trump. “Any breaking news?” Bannon asked Winters. “Uh,” she replied, “Lawrence O’Donnell has melted down about the Electoral College on MSNBC.”

“That’s a great tell,” Bannon said. “When they’re bitching and moaning about the Electoral College, that’s when you know you’ve got ’em.”

Off the balcony, the Monument Lounge was starting to fill with fans of War Room. Erik Prince thumbed quietly through his phone at a conference table set with trays of catered cold cuts. (“I’m a friend of Steve’s,” he said, declining further comment.) Jeffrey Clark, a former Justice Department official who was indicted in Georgia and faced disbarment proceedings in Washington for his role in Trump’s fight to overturn the 2020 election, showed up around 10 p.m. “Jeff Clark’s over here,” Bannon said. “He’s going to be the future attorney general — the first one ever without a law license, I might add.”

“Did I hear my name being taken in vain, Steve?” Clark said cheerfully to Bannon as he stepped off the set and went to another balcony to do an interview with All-In, a podcast co-hosted by tech investor David Sacks, a Trump supporter and a close ally of Musk’s. Bannon jovially jousted with Sacks & Co. on behalf of the working class. “That’s that hedge-fund crowd,” he said when he was done. “I had to blow him up.” The exit polls suggested that Trump had doubled his support among young Black men, just as Bannon had predicted. “The brothers came through,” he boasted to a friend in the lounge.

Around 12:30 a.m., Bannon received word that Trump was on his way from Mar-a-Lago to the Palm Beach convention center to give a speech to his supporters. Bannon barked to his producers, ordering up a live helicopter shot of the motorcade and a cup of black coffee. He then took a phone call off-camera. (“It’s not him,” Bannon whispered to me. “It’s the people around him.”)

“Let’s go to West Palm Beach, guys,” Bannon, back at his desk, said a little after 1:45.

“Fox is calling Pennsylvania,” his producer interjected.

“Yep, it’s over,” Solomon said.

Bannon clapped, pumped his fist, and announced, “President Trump is the president of the United States.” He hugged Winters, let out a loud whoop, and shouted, “Fuckin’ A!” Then he brought a bunch of his supporting players, including Clark, behind the table. One of his correspondents, Noah Benjamin, offered a prayer of thanksgiving: “Lord, you have moved mountains and you brought back your chosen leader, President Donald Trump, for this nation.”

“Amen,” Bannon said. “Back to work.” With scarcely a breath, he turned to his next item of business: revenge. “Merrick Garland, when we throw you in prison, Jack Smith in prison,” he said, once again name-checking Clark, “remember that it’s Jeff who you tried to destroy that’s going to have the ultimate blowback on you guys.”

“It’s not retribution,” Winters said. “It’s justice.”

It was a resounding victory; contrary to Bannon’s expectations, November 5 was the end of the election after all. Trump delivered his victory speech, and the War Room staff broke open the wine and beer. The next morning, when they reconvened at the basement studio, everyone looked unusually rough — except for Bannon, who usually looks that way. (He says he hasn’t had a drink since 1998.) Even on two hours of sleep, Bannon’s mouth could keep flying like a B-52 on autopilot. When the 10 a.m. edition of the show was over, Winters went off to look at apartments. She said she planned to relocate to Washington in time for the transition.

Bannon invited me upstairs to the parlor floor, which was decorated in a more stately fashion than the basement with antique furniture and a nautical oil painting. During and after the 2016 campaign, he said, when he was inside or close to the White House, he had hosted salonlike dinners at the townhouse. But he had rarely used it since 2020. Bannon saw COVID coming early. He shuttered the house to outsiders and turned War Room into a show about the pandemic. Since then, he has proceeded from crisis to crisis: his federal indictment in a scheme to build a donor-funded border wall, the 2020 election, January 6, the investigations, the McCarthy ouster, Trump’s trials, his contempt sentence. There apparently hadn’t been much time for cleaning. The parlor was cluttered with books and dusty, a first-term time capsule.

“Never in 1 billion years did they ever think that we would be where we are today, that Trump would be back, that we would have the House and the Senate, and Steve Bannon would be a thing again,” he said. “They’ll pay for their arrogance, as they should. The American people rendered a verdict.” And that verdict was, Bannon said, “‘Go fuck yourself. We want this guy back.’”

I pointed out to Bannon that just eight days before, he had been in Danbury. “Holy shit,” he replied. “That is wild.” In just a week, he had gone from prison to the precipice of a second Trump term. Bannon’s friends were now about to take new roles in the government. Trump wouldn’t put Clark in charge of the Justice Department, but he would do something maybe just as outrageous: nominate Gaetz to be attorney general. Reportedly, the decision came at the urging of Gaetz’s fellow War Room regular Epshteyn; Bannon would text me that the move was “Dawn of Earth huge.” Patel is rumored to be up for a top role at the FBI or an intelligence agency. The nominations of Tulsi Gabbard for director of national intelligence and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. for Health and Human Services secretary are also in their own ways expressions of Bannon’s brand of nationalist, conspiratorial, very online politics. “Probably half of my guests will go into the administration,” Bannon said, filling roles up and down the organizational chart.

Given Bannon’s history — and the fact, despite a 2021 pardon from Trump, he still faces New York State charges in the border-wall case — it is unlikely that he himself would ever go back into government. But he said his platform offers its own form of power. “We have a mission here; the mission is to push Trumpism and Trump,” he said. “You don’t have to be sitting next to him to do it.” He sees himself as a counterweight to the “billionaire populists” competing for Trump’s ear, like Musk and Sacks, who are attuned to the priorities of Silicon Valley and what he describes as “globalist” values.

I asked Bannon if he had meant what he said about imprisoning the leadership of the Justice Department. “I think Merrick Garland, Jack Smith, Lisa Monaco — I think they’d better lawyer up,” he said. During the campaign, Trump routinely called for criminal investigations of his prosecutors and accusers and for a purge of the “crooked” justice system. Now he is demonstrating he really meant it by sending Gaetz and members of his own defense team to take over the department. (The lead lawyer in Trump’s New York criminal trial, the former federal prosecutor Todd Blanche, is now in line to be deputy attorney general.) Pandora’s box has cracked wide open. “They should be scared. They’ve committed crimes,” Bannon said. “He’s going after Liz Cheney on witness tampering. Liz Cheney’s going to lecture us on democracy and guardrails? Guardrail this, baby.”

Bannon expects resistance. The Democrats may be humiliated now, but he assumes they will soon regroup, and he anticipates “a firestorm” before Trump takes office. “We have to get the pus out of the system,” Bannon said. The poison, in his view, is the zeal that led to the prosecution of a president and his movement’s leaders in the name of the rule of law. Democrats called that “accountability,” but Bannon feels it was vengeance, and now it’s time for the cycle to turn on those who had tried, and failed, to stop the return. Bannon knows his postelection message is unlikely to offer comfort. “People come to me all the time, saying, ‘You’re so negative, and you’re so hard, and you come across with so much vitriol and so much meanness,’” he told me. “I go, ‘Dude, this ain’t morning in America.’”