This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

To its owner, a sports team is more than just a plaything. If you happen to have the billions it takes to acquire one, you presumably have a near-infinite number of ways to spend your money. By buying a team, an owner can reveal their inner winner — or make people forget how they made all that money in the first place. Thus, a shipbuilder and Watergate bit player named George Steinbrenner could take over the Yankees and turn himself into The Boss. If his dad had never bought the Knicks and the Rangers, Jim Dolan would just be an angry guy who used to own a cable company. An owner gets to play fantasy in real life, going to work at a park. And what other trophy asset can end up yielding an actual trophy?

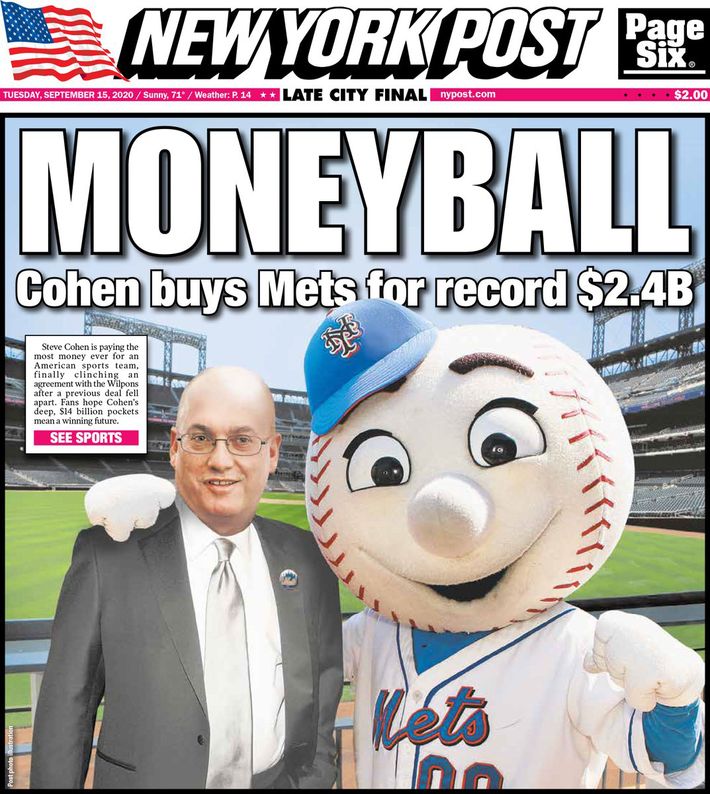

If everything had gone according to plan, Steven A. Cohen might have been parading down the Canyon of Heroes this month. When he purchased the New York Mets in 2020 for a record-setting price of $2.4 billion, Cohen promised to restore his favorite team from childhood to glory, saying he would be disappointed if he did not bring it another World Series within “three to five years.” He then assembled the highest-paid roster in baseball history. The ecstatic Mets nation treated the richest man in baseball like he was a free-spending folk hero. At 67, Cohen, a Stamford-based hedge-fund manager, has $14 billion according to Bloomberg, or maybe $19 billion if you believe Forbes, but at any rate, a whole lot of money — seemingly more than enough to procure a championship. Some fans took to calling him “Uncle Steve,” a nickname that seems to please the proprietor.

“I don’t know how it started, but I think it’s endearing,” Cohen said one foggy morning in late October in his office, which overlooks the Long Island Sound and is decorated with pieces from his world-class art collection. He had on the same outfit he wears to work most days at his asset-management firm, Point72, a collared shirt beneath a light-blue zip-up sweater with the Mets logo embroidered on its breast. As we talked baseball, Cohen’s pale-blue eyes kept darting to the open laptop in front of him. Four other screens on the wall were set up to display data on the markets, including a position board listing his stocks. “It’s a special property,” he said of his team. “It’s in New York. Fans are passionate; they love the Mets. So I had a real opportunity to take on a project that was going to take up some of my time, but if I was successful, I was going to make millions of fans happy.”

Cohen glanced toward his position board on the wall.

“I have this other job that I make a reasonable living from. So this was more — I would actually call it more philanthropic.”

Being a hedge-fund manager, Cohen has said, “doesn’t mean much to people.” In fact, the emotion it promotes in many Americans is rage against a system in which a small handful of plutocrats possesses so much, flouts the rules, and gets away with it. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, Cohen’s previous hedge fund, SAC Capital, was the subject of an insider-trading investigation that resulted in multiple federal convictions and SAC’s dissolution. (Cohen was never criminally charged.) The investigation was thinly fictionalized on the Showtime series Billions, in which Damian Lewis plays a considerably more handsome financier modeled on Cohen. In the recent film Dumb Money, about a populist short squeeze on hedge funds, Cohen is depicted as a crass slob throwing cold cuts to a pet pig. Although he would never admit he cares about the caricature, buying and supercharging his favorite ball club seemed like the sort of thing a legacy-minded billionaire might do.

It would be a mistake, though, to see Cohen’s baseball play as purely benevolent. He had a second angle to his plan for the fall — one that stood to make him even richer. When Cohen bought the Mets, he inherited the lease on a giant piece of land: the parking lot next to Citi Field. Almost from the moment he took over, he has been building support for a plan to turn the long-neglected area into an entertainment megaplex. Its anchor would be a casino, one of three that the state government is preparing to license in the New York City region. The $8 billion project, called Metropolitan Park, faces opposition from some environmental groups in the area and competition from most of New York City’s big real-estate developers, who are all battling for the limited supply of licenses. But if he builds it, the gamblers will come, creating revenues far exceeding anything the Mets might ever generate. In the casino business, the home team always wins.

A New York casino is not something Cohen can just buy, at least explicitly. He will have to pass through a political process requiring him to win over everyone from Governor Kathy Hochul to a measly city councilman. This has required a man unaccustomed to seeking permission to exercise his rusty powers of persuasion. During the baseball season, Cohen would sometimes spend his day trading at his Citi Field office, then walk around the concourse to enjoy a ball game from the owner’s box, sharing his hospitality with politicians and community leaders. He has invited residents out to the ballpark for forums on redevelopment, offering the public a chance to give input and mixing with regular folks from the neighborhood. He has sprinkled millions in Mets-branded charity all over Queens.

Uncle Steve’s winning aura depended on an unpredictable element: wins. There was every reason to think that this season the Mets could be in the World Series, right on Cohen’s three-to-five-year schedule. But as every baseball fan knows, it didn’t turn out that way. “I was waiting and waiting for the team to show some consistency, and it never did,” Cohen said. In July, in characteristically cold-blooded fashion, he gutted the team, trading high-priced stars for unproven prospects and writing off much of his expensive roster as a sunk cost. This October, Citi Field was quiet, but the team offices out in right field were abuzz as Cohen purged and prepared for another active offseason. The many lobbyists and political strategists on the casino project were hard at work too, offering peeks at the plans, twisting arms, and preparing for a hard political battle.

“He is approaching politics the way he is approaching Mets ownership,” says a consultant to a competing casino bidder. “The question is whether it will have the same results or not.”

Growing up on Long Island, Cohen was a Little League pitcher, but he was better at poker. He ended up as a trader on Wall Street, where he displayed uncanny skill as a stock picker, shifting positions in an instant, riding the momentum of the market. Over two decades, his hedge fund, SAC Capital, delivered spectacular annual returns, averaging 29 percent over two decades. There was suspicion that his market timing was just a bit too perfect.

In the 2010s, the then–U.S. Attorney in Manhattan, Preet Bharara (now a podcaster for New York’s parent company), built a case that SAC was trading on inside information. One portfolio manager went to prison for enticing a doctor to leak the disappointing results of a study of a biotech company’s Alzheimer’s drug — information he used to make trades. According to evidence in the legal proceedings, Cohen suddenly switched his position in the company from long to short after talking to the portfolio manager. He was not prosecuted, but SAC as a company pleaded guilty to federal securities- and wire-fraud charges, accepting a record $1.8 billion fine. The Securities and Exchange Commission charged Cohen in a related civil case, which he told me was “aggressive,” considering that the worst thing the government could prove after so much investigation was that his employee had committed crimes. “I ended up getting a ‘failure to supervise,’” Cohen told me. “I would call that a misdemeanor.”

Cohen settled with the SEC, agreeing to a ban that temporarily prohibited him from managing external capital. He continued to invest his personal wealth and, after a few years, was able to start anew with Point72. He turned his attention to other pursuits — ones that might help to refurbish his reputation. According to Sheelah Kolhatkar’s book Black Edge, as far back as 2011, one SAC executive, Michael Sullivan, assured the staff of a U.S. senator who wanted the SEC to investigate the hedge fund that Cohen was “very civic minded.”

“He’s thinking about taking a stake in the New York Mets,” Sullivan reportedly said.

Cohen told me he considered the Mets franchise an “unpolished gem.” The majority owner, real-estate developer Fred Wilpon, had run into financial trouble as a result of his investments with Bernie Madoff. Cohen started off by trying to acquire a minority stake in the team in 2011. But the deal fell apart, as did his subsequent bid for the Los Angeles Dodgers. There are 30 Major League Baseball franchises, and the owners act as a collective when it comes to allowing access to their club. Any purchase requires approval by a supermajority vote. There was speculation that the owners as a group were blackballing Cohen because of the then-ongoing insider-trading case.

If there is one thing that drives Cohen, and plenty of other wealthy people, for that matter, it is being told he can’t have something. This is a man who bought Picasso’s Le Rêve not just once but twice. (Famously, the first sale, for a record-high price of $139 million, was ruined when the selling party, casino magnate Steve Wynn, accidentally put his elbow through the canvas. Cohen waited seven years and bought the repaired painting for an even higher price: $155 million.) So Cohen was not going to give up on baseball just because of a couple of dents.

In 2012, Wilpon agreed to sell him a 4 percent stake as part of a consortium that invested $240 million to stabilize the Met’s finances. “You buy a minority interest in the team, it’s like buying a season ticket,” Cohen said. He wanted more. “If I’m going to get involved in something in a serious way, and if I’m going to spend time on it, I’m going to want decision-making authority.” When Fred Wilpon had a dispute with his brother-in-law and partner over his desire to hand the team over to his son, Jeff Wilpon, Cohen was pre-positioned.

The club went up for auction in the midst of the weird and empty pandemic season of 2020. Cohen had to beat out a group led by the former Yankees star Alex Rodriguez, his then-fiancée, Jennifer Lopez, and e-commerce billionaire Marc Lore, who just so happened to be a friend of Bharara’s. Most of the owners preferred Cohen to A-Rod, but a faction remained stubbornly opposed. Small-market team owners are militant about ensuring that big-market teams don’t overwhelm them with spending. Cohen passed by four votes.

“Listen, that’s their job to be the gatekeeper,” Cohen said. “I’ve got to exist in an ecosystem that has its own culture and ways of doing things, and I am not here to be a sand in the clam. I’m here to work with them and help them think about the future of baseball.” He confirmed the word I had heard around the baseball industry: that he had offered his fellow owners assurances before the vote that he was committed to controlling players’ salaries.

“I have done that,” Cohen said. “And I have followed all the rules.”

In a literal sense, that is true. Unlike other American sports, baseball lacks a hard salary cap. To ensure competitive balance, the league sets a ceiling on payroll that teams are expected to stay under. Those that exceed the threshold incur a “luxury tax,” which is redistributed to teams under the ceiling. Overspending is not against the rules, but the owners treat it like misbehavior, and the penalties escalate for repeat offenders. Cohen went right up to the luxury-tax ceiling in 2021 and exceeded it the following offseason. After a brief lockout in the spring of 2022, the owners made a deal with the players union that featured new luxury-tax penalties, including a punitive top tier that people dubbed the “Cohen tax.” He would soon blow right through that higher ceiling, too.

“Steve can buy out every owner three times over in terms of his net worth,” says one baseball-industry executive, exaggerating only slightly. “He likes that, and he uses that.”

To Mets fans, his greed was good. Cohen got into the fray with them on Twitter, mouthing off like he was just Stevie from Great Neck, cheering and occasionally jeering his players. He would playfully stoke speculation about his personnel moves, asking his followers to “play GM” with him. To actually run the team, Cohen brought back Sandy Alderson, who had been general manager during the 2015 World Series run. Alderson had pioneered the use of baseball analytics — he was the mentor of Billy Beane, the protagonist of Moneyball. But if Moneyball was about identifying market inefficiencies and doing more with less, the Mets would be doing more with more and more. As soon as Cohen purchased the team, he traded for star shortstop Francisco Lindor, whom he signed to a ten-year, $341 million contract extension. For the 2022 season, Cohen signed pitcher Max Scherzer to a contract that paid him $43 million a year, the highest annual salary in history. The next offseason, after the Mets suffered an early playoff elimination, Cohen went out and added pitcher Justin Verlander at the exact same salary as Scherzer, along with other high-priced free agents. The spree brought his payroll this season to $379 million, on top of which he was projected to pay $107 million in luxury taxes. The tax hit was more than the entire payroll of nine teams, three of which ended up making the playoffs. He was playing by the rules, as he read them, accepting the penalties as a cost of doing business.

At the time, no one in New York was complaining. On opening day, Cohen invited a bunch of Queens politicians who had a say on the casino out to the ballpark. He took a selfie by home plate with Borough President Donovan Richards and City Councilman Francisco Moya. State Senator Jessica Ramos, an outspoken young progressive who grew up in Astoria, was also there for the festivities. “As a Mets fan,” she told me of Cohen’s investment in the team, “who couldn’t be happy?”

Willets Point, where Citi Field now stands, was originally a Flushing Bay marsh and later a dump, part of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s famous “valley of the ashes.” It has long been a target of real-estate power plays. Robert Moses turned adjacent land into Flushing Meadows–Corona Park for the 1939 World’s Fair while encircling Willets Point with roads and highways. During the Bloomberg administration, the Wilpons and the Related Companies proposed turning the east side of Citi Field, a polluted strip of chop shops, into housing and offices while putting a shopping mall on the huge parking lot to the west. There was a lawsuit, and a court ruled that the parking lot, which used to be the site of Shea Stadium, could not be redeveloped because it was technically parkland leased by the Mets.

Cohen told me he “ascribed almost no value” to the parking lot when he bought the team. Then, amid the pandemic budget crisis, the state government created an opportunity, starting the process of licensing three casinos in the New York City region. The casinos will bring the state licensing revenue in the short term — the initial fees, projected to be $1.5 billion, will go to the MTA — and taxes over the long term. For anyone who ends up winning the right to build a casino in the city, the potential payoff will be “an insane amount of money — insane,” says an executive at a company that is bidding. He adds, “This has long been considered the Super Bowl of New York real estate.”

“All of sudden it was like, Okay, we have an economic engine,” Cohen said. That is, if he could navigate the complicated approval process. For all the bidders, the first hurdle is winning the endorsement of a committee on which the local member of the City Council, both state legislators, the borough president, the mayor, and the governor all get a vote. Cohen’s project in particular has to clear another barrier: persuading the State Legislature and City Council to vote to “alienate” the parkland, which will allow it to be used for a purpose other than parking. Then he will have to beat out other bidders, which include a partnership between real-estate firm SL Green and Jay-Z, who want to put a casino in the old MTV studio in Times Square; Related, which is developing a plan for Hudson Yards; and the company that owns Saks Fifth Avenue, which wants to repurpose the store’s top three floors. Besides Cohen, there are several serious bidders outside Manhattan, including existing racetrack casinos in Yonkers and at the Aqueduct, which want to expand and add gaming tables. But Cohen’s team says his site has the most potential.

“It’s kind of a black hole out there in the wintertime,” said Michael Sullivan, a Point72 executive who serves as the on-field manager of Cohen’s political interests. Known to all as “Sully,” he is a former congressional staffer and the same person Cohen dispatched to the senator’s office in Washington more than a decade ago. When we met at a café in Jackson Heights, he repeated a familiar note, telling me right off the bat that the Mets were his boss’s “civic project.” For the past few years, Sully has been meeting with Queens community groups and showing up at even the smallest neighborhood events. “The Mets are everywhere,” says Donovan Richards, the borough president. “If I show up to a dinner tonight, I may see the Mets there.”

Like a few community leaders and politicians, Richards has gotten an advance look at Cohen’s plans. He says he was “blown away” by what he saw at the offices of the architecture firm SHoP, where the renderings were presented in a 360-degree projection room. SHoP, which designed the Barclays Center and the Domino Sugar development, has experience with politically sensitive mega-projects and has repeatedly revised the plan based on community input. Because the site was originally a soft wetland, construction will be difficult. In order to free up the huge lots next to the stadium — the area his team describes as “50 acres of asphalt” — Cohen intends to build at least one parking garage on the far side of the Willets Point 7-train stop, the construction of which he says will be “wildly expensive.” About half of the 50 acres could then be turned into a landscaped park with pedestrian and bike paths connecting the subway station to the Flushing Bay marina.

The western side of the site would be reserved for what Cohen’s advisers insist on calling an “entertainment center.” Besides a casino, it will include a hotel and concert hall. Cohen has a deal with the Seminole Tribe of Florida, which owns the Hard Rock Casino chain, including its flagship near Fort Lauderdale, which resembles a giant guitar. For now, Cohen’s team says it is keeping further details of the plan confidential for competitive reasons, although Gregg Pasquarelli, the founding principal of SHoP, told me he is aspiring to create “a civic building in a park that happens to have a gaming floor in the middle of it.” So nothing guitar-shaped.

Richards says Cohen impressed him with his efforts at community engagement, which have been led by lobbyist Julissa Ferreras-Copeland, a former City Council member whose district included Willets Point. She has run the community forums at Citi Field, which Sully told me had yielded an overwhelming consensus. “They want good-paying jobs,” Sully said. “They want jobs with upward mobility. They want jobs with job training, and they want jobs with child care for people who need it. Jobs, jobs, jobs.” A casino would create construction jobs, hospitality jobs, card-dealing jobs — and all of them union jobs, Sully said.

That prospect sounds promising to many residents of the low-income area, which Richards notes was the “epicenter of the epicenter” of the pandemic. Cohen has made many friends there through his generosity. He started off by giving $17.5 million to the city government to distribute COVID-relief grants to small businesses, restaurants, and street vendors in Queens. “I was Santa Claus,” says Richards, who got to distribute the money. Cohen and his foundations have since given millions more in grants to Queens nonprofits and charities. The Reverend Patrick Young, the pastor of the First Baptist Church in East Elmhurst, told me about an event at his church, which he said Cohen had financially supported, where then–Mets infielder Eduardo Escobar helped to serve 2,000 people free steak. Young has been a vocal supporter of the casino. It would be cynical to attribute Cohen’s giving entirely to self-interest, but he was certainly playing the game.

All the casino bidders have hired lobbyists, flacks, and political consultants, who have been busily wooing politicians, gathering oppo, and trying to sink each other’s battleships. In this, as usual, Cohen has blown away the competition. “For him, it’s like a sportswashing exercise, and he can spend an unlimited amount of money,” says a communications consultant who is working for a competitor. Besides Ferreras-Copeland, Cohen’s lobbying team includes Bradley Tusk, the former Bloomberg and Uber strategist, and a charter-school advocate who ran a super-PAC that supported Eric Adams’s mayoral campaign. (Cohen gave the super-PAC $1.5 million.) Besides his lobbying expenses, which legally have to be disclosed (see sidebar below), Cohen is also paying additional undisclosed consulting fees for political and communications advice, polling, planning, engineering and field outreach.

The ultimate decision on the casino will be made by the State Gaming Commission, which is chaired by an appointee of Governor Hochul. The Gaming Commission investigates all key casino investors and possesses wide latitude to reject them on grounds of “character and fitness.” Some of Cohen’s competitors say they see vulnerabilities for him at this stage of the process because of his history with regulators and law enforcement.

“Ooooh!” Cohen said sarcastically, when I brought up the potential lines of attack. “My attitude is I’m not worried about it. I’m pretty seasoned, so things just fall right off me.”

Still, Cohen has worked to make allies, sometimes through baseball diplomacy. Pastor Young told me he had visited Cohen in his owner’s box “several times” — on one occasion during a 2022 playoff series against the Padres. “The first game, they had Governor Hochul there and they lost,” Young said. “Then we show up and they won.” Hochul dropped by the ballpark again at the beginning of June and took a photo with Cohen.

Maybe it was a bad omen, because the Mets started losing in June — again and again and again. After going 7 and 19 that month, Cohen decided to reconsider his strategy. He had spent so much, so fast, to build the team, and he would just as quickly plunge the detonator.

He’s a probabilistic thinker,” Mets GM Billy Eppler told me in late September, as we sat at a high table in a Citi Field luxury box next to his boss’s unoccupied suite. Out the window, there was a crack and a roar as Lindor socked a homer, one of two he’d hit in the game. Eppler was only halfway paying attention. It was hard to pin the team’s failure on any one flaw. There had been a freak injury (to dominating closer Edwin Díaz), age-related regression (Scherzer and Verlander), and some inexplicable slumps (slugger Pete Alonso). “When people aren’t achieving, or when systems or teams aren’t achieving, the results that they want to achieve, they always want to understand a reason why,” Eppler said. “They don’t want the answer to be randomness or bad luck.”

There was an argument for patience. The 1973 Mets had an even worse record in mid-July and went on to the World Series. Ya gotta believe! “You know what I call that?” Cohen said. “Magical thinking.” Cohen thought the team was too old, too slow. Ahead of baseball’s August 1 trade deadline, he shipped off Scherzer, Verlander, and other veterans.

“It was a very hedge-fund-like response to the situation that the team was in,” says Sandy Alderson, who remained an adviser to Cohen after Eppler took over management. He could exchange an abundant resource, his money, for a scarce one: future talent. In return for paying out almost all of Scherzer and Verlander’s contracts, at the cost of $70 million, the Mets received a collection of prospects. The most promising of them was Luisangel Acuña, the brother of superstar Atlanta Braves outfielder Ronald Acuña Jr. “It’s the exact thing that made people reticent when they approved Steve,” says David Samson, a former executive with the small-market Marlins who now has a podcast and has publicly tussled with Cohen. “Using your money like that, that’s dangerous because it’s so smart.”

“We needed to make a pivot,” Cohen said. “And I actually felt like it wasn’t a hard decision at all.” Not that he was accepting of failure. He was famous for summarily firing underperformers at SAC. Before the season’s final game, the Mets’ popular veteran manager, Buck Showalter, choked up and told reporters he would not be returning in 2024. The following day, Cohen held a press conference at the ballpark. The owner, who looks much thinner than in years past, was wearing a baggy dark blazer over his usual zip-up sweater. “I kind of orchestrated all of this,” Cohen said, addressing Showalter’s termination with the air of someone who seldom has to explain why he had given anyone the axe. “I obviously appreciate all that Buck did for the organization and for me. And so that’s that.”

With his unfinished business squared away, Cohen introduced his first offseason acquisition, David Stearns, a Harvard-educated hotshot who would become the Mets’ third top front-office executive in as many years. Although Stearns was coming in with the title of president of baseball operations, above the GM in the hierarchy, Eppler was sitting in the front row of the press room. Cohen told the press that Eppler would continue to work under Stearns, saying he viewed the arrangement as “one and one equals three.” Eppler lasted just three days before he too was out the door. His abrupt resignation appeared to come as a shock to the organization. It soon emerged that the general manager had run into an unexpected mess of his own.

The specific allegation — that Eppler had manipulated the roster by placing healthy players on the injured list — was almost laughably minor. Baseball teams routinely bend the rules by stashing players on the list with phantom injuries. What was significant about the investigation was the fact it existed and became public. The New York Post reported that investigators from the office of MLB’s commissioner had descended on Citi Field to conduct interviews.

“Baseball’s Mets Investigation Will Seek to Answer What Steve Cohen Knew,” read the headline on a story in the Times, which reported that MLB commissioner Rob Manfred was taking special care with the cheating probe, given Cohen’s history. Conflicting stories reported that Cohen was not a target. People in the organization were wondering who had sent in an anonymous tip ratting out Eppler. The news was filled with postmortem reports of dissension: players calling one another out for laziness, Showalter feuding with management, Alonso acting disgruntled.

Everyone involved was denying or deflecting, and everyone on the outside was confused. One political consultant — admittedly, a Yankees fan — described the situation as “Wilpon-esque.” Even with Cohen in charge, it seemed the Mets still had some LOL in them. A former investor in the Mets told me: “There’s no other way for you to write it other than ‘Insanity at Citi Field.’”

The first signs of trouble for Cohen’s casino emerged around the time that the Mets started falling apart on the field. Cohen was finding that Queens politicians were not as easily bent and broken as his rivals on the trading floor. In May, the nonprofit news publication The City reported on a rift between the Mets organization and the Adams administration, which was trying to finally get moving on the latest iteration of the Bloomberg-era plan for the east side of the stadium, which now calls for 2,500 units of affordable housing, a school, and a new soccer stadium for the professional club NYC FC. The soccer stadium requires parking. The obvious solution would be to share with the Mets, but Cohen was not being neighborly. It leaked out that Cohen was withholding his support unless everyone backed his casino plan.

“They need our parking,” Cohen told me. “And I want to be supportive of them, but I need them to be supportive of us.”

In baseball terms, it was a brushback pitch aimed at one person in particular: City Councilman Francisco Moya. A rabid soccer fan, Moya desperately wanted the stadium built in his district. (He has a local magazine cover depicting him as Ted Lasso, in an NYC FC sweater, pinned at the top of his Instagram feed.) Cohen reportedly tried to squeeze Moya tighter in a conference call that included Mayor Adams. There are varying accounts of what transpired. Sources told the Post that Cohen informed Moya that if he withheld support for the casino, he would support a potential Moya primary challenger, the disgraced former state legislator Hiram Monserrate. Cohen’s representatives called the report a “complete fabrication,” and other people who heard directly or indirectly about the call told me the threat was more general though still intimidating. Whatever happened, multiple sources say Moya was furious.

“Francisco, he’s still trying to figure it out,” said Cohen, who has continued to lobby the councilman both directly via Sully and through the firms he is paying. Jeffrion Aubry, the local state assemblyman and a supporter of the casino, said that while he was not directly involved in the conversations, it was his understanding that Moya had previously indicated support for the casino. “If all of a sudden for some reason you decide you don’t want to fulfill those commitments,” he said, “you have the right to do that, but people have a right to not be happy.” The argument created a significant threat to the casino bid. While members of the City Council are relatively powerless when it comes to doing things, they have great authority to stop things and hold an effective veto on land-use decisions in their districts.

Through a spokesperson, Moya denied that he had ever indicated to Cohen that he supported the casino or fought with him over the soccer stadium. He declined numerous interview requests over three months. On September 8, the spokesperson said he was dealing with “a severe family emergency” and would be unable to speak to the press. (His father died in October.) That same week, he conducted several back-to-school constituent events co-sponsored by the Mets, taking a photo with Mr. and Mrs. Met at one, and attended a pregame ceremony at Citi Field, where he appeared on the scoreboard to call out, “Play ball!” And that may be just what he and Cohen are doing.

Other sources of local opposition could be less amenable to Cohen’s pitch. Some environmental advocates question the long-term viability of a gigantic development built in an area that already floods regularly, a problem that will only worsen with climate change. (Cohen’s team says the development is designed to improve drainage problems.) Activists in next-door Flushing, home to a huge Chinese immigrant population, suspect that their area has been targeted because casino companies stereotype Asians as avid gamblers. These and other concerns were aired over the summer at a town hall hosted by State Senator Jessica Ramos where casino opponents faced off with a group of boosters carrying signs paid for by Cohen’s group. At the meeting, Ramos announced that she was refusing to support the plan for the time being.

Ramos’s position gave her the power to determine whether the casino would be built. While Aubry had introduced the alienation legislation that Cohen needed, for it to become law she had to put forward a counterpart bill in the State Senate. “I’m deeply skeptical,” she told me when we met at an Ecuadoran restaurant in Corona one afternoon in September, “and I have a lot of needs.” For starters, she said she was seeking a firm commitment on the use of union labor and a binding agreement that would hold Cohen to his promises of community benefits.

Ramos, 38, has aspirations that are larger than Queens; there is speculation that she is thinking of running for mayor against Adams. She told me that Cohen’s lobbying team had been pestering her to take a politically charged position before she was ready. “I do resent the pressure,” Ramos said. Actually, she seemed to be enjoying the opportunity to bat around the billionaire like a cat with a ball of string.

Ramos took me on a walk down Roosevelt Avenue, which was thick with street vendors selling fruit and tacos. “We don’t want to sell ourselves short,” she said. “This project is going to produce billions for years.” When we got to Citi Field, a handful of tailgaters were grilling in the parking lot ahead of that evening’s game, but mostly it was desolate and dotted with puddles. Ramos gave me a site tour, based on what she had seen in her visit to SHoP: 20-acre park right in front of us, “Taste of Queens” food hall to the right, and, to the left, the casino, which she said looked like Lincoln Center in the renderings. She said she was still willing to be convinced.

“There is no one defending the asphalt,” Ramos said. But she wanted some concessions, and she said she was surprised that Cohen seemed not to recognize her leverage.

“Aren’t they experts in risk management?” she asked. “I’ve watched Billions! What the fuck?”

Cohen still trades stocks every workday, even though he has an entire building filled with fleece-clad employees. In the Point72 lobby there hangs a Barbara Kruger painting that consists of just two giant words: HOW MUCH? During the day, he sits at a desk with a camera trained on him, speaking to his traders through a microphone. “I mean, this is the core,” he told me as we sat at a big round table with Sully and one of his public-relations people. His cell phone chimed at one point, and Cohen told me he had to take a call. The opening bell was about to ring.

“All right,” he said. “Why don’t you buy me 200 between, say, 43 and three-quarters and 43.”

That night, Max Scherzer was slated to start game three of the World Series for the Texas Rangers against the Arizona Diamondbacks. Cohen said he was “absolutely” planning to watch and told me he had sent Scherzer a text congratulating him on the success of his new team. Cohen had reason to be satisfied, too: Scherzer had been injured and ineffective since July, which meant he had timed his trade well. His confidence in his judgment was unshaken. “This was an opportunity to do some transformative changes,” he said. “I can make those decisions. I’m good at it. Some things are clear to me. I thought that was pretty clear. And I think people were struck with it. They had never seen anybody do that before in baseball.”

The Mets were going into the offseason with $228 million in salary on the books and little hope of competing without major additions. It is possible that the new front office could go for an incremental approach to rebuilding, working in young players while filling holes on the free-agent market. Or Cohen could make a big move. At the end of our interview, I asked him about speculation that he might go for Shohei Ohtani, the multitalented (and often injured) Japanese superstar, who is thought to be seeking a contract worth $500 million or more this offseason.

“He’s a great ballplayer,” Cohen said with a thin smile.

After all, what is half a billion here or there when the benefits of winning — for the fans, for the city, for Cohen’s ancillary ambitions — are so tantalizing? “If you really want to make something happen,” he told me of his long quest to own the Mets, “you have to risk that you may not get it.”

On the first night of baseball’s playoffs in early October, Cohen spent an evening at Citi Field, working on his second project. He had invited a select group of friends from Queens out to the otherwise empty ballpark to participate in another forum about his plans for redevelopment. Inside the Piazza 31 Club, behind home plate, the attendees filed past a series of placards on easels, each devoted to a different development priority: jobs, environmental resilience, green space, year-round activity. Facilitators directed residents to put colored stickers next to specific amenities. The word casino hardly appeared anywhere.

Cohen was in the midst of the throng, chatting with Sully and Assemblyman Aubry. A long line waited for a moment with the billionaire. A group spoke to him at length in Spanish through a translator. Behind them were some Chinese American seniors from Flushing.

“Pastor!” Cohen said, accepting a chest bump from Patrick Young.

Greg Coles, 67, walked up to thank Cohen for giving $5,000 to sponsor a Mets-branded car in the Flushing Meadow Soap Box Derby, which Coles helps to organize. A lifelong resident of East Elmhurst, Coles was wearing a ’69 Mets commemorative jersey. “I think we made a mistake,” he said of his favorite team, “and now we have to correct the mistake and move forward.”

Everyone sat down for a ballpark dinner. Sully waved me over to the owner’s table. Cohen watched impassively, squirting ketchup on a Shake Shack burger, as Gregg Pasquarelli made a historical case for reconnecting Willets Point with Flushing Meadows–Corona Park. “How many times do we get the opportunity to right the wrongs of Robert Moses?” the architect asked. Sully warned the audience that competing bidders were spending money “to fabricate opposition to this project” in Queens. “So what I need all of your help with is,” he said, “to make sure a handful of voices from folks, many of whom probably won’t be from Queens, don’t drown out the overwhelming support we have.”

Before the dinner, I had had a chance to chitchat a little with Cohen, as he stood in front of the last of the easels his team had set up, which had the heading THE CHOICE.

Option 1 was: “Keep 50 acres of asphalt parking until the year 2105.”

Option 2 was: “Build something great for all.”

All the stickers were on the side of Option 2.

I pointed out that he was winning in a landslide. Cohen pursed his lips and told me that you never know with elections. When I later asked him if it would be possible to build “something great” even if the casino didn’t work out, he told me no. “It’s economically not feasible,” he said. “Which is disappointing.” There was really no choice, he said. It had to be his way or nothing at all.