Swift, more than nearly anyone else on the planet, has personal reasons to worry about impersonation and misuse of her likeness through AI. She’s incredibly famous, and her words carry weight for lots of people. As such, when it comes to AI, her experience has been both futuristic and dystopian. Like many celebrities — but especially women — she already lives in a vision of AI hell where the voices, faces, and bodies of famous people are digitally cloned and used for scams, hoaxes, and porn. (Last year, explicit and abusive deepfakes of Swift were widely shared on X, which took the better part of a week to slow their spread.) Her endorsement can be understood as an attempt to reclaim and assert her identity, as well as her massively valuable brand, in the context of a new form of targeted identity theft. “The simplest way to combat misinformation is with the truth,” she writes. (Do not read Elon Musk’s response.)

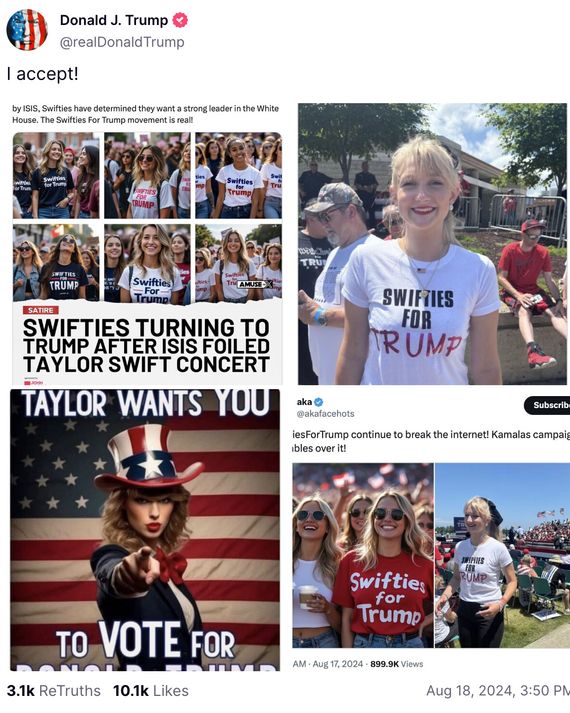

The thing about the false endorsement to which she’s responding, though, is that it probably didn’t need to be refuted. On Truth Social, Donald Trump shared a collage of trollish posts and AI-generated images: Two of them had a photo of the same woman; one still had a visible “satire” tag; and another, while clearly generated by AI, was rendered in the style of an illustration. It’s ridiculous.

But it’s ridiculous in a particular way that’s become miserably familiar in recent years. It’s not quite a joke — more of a taunt — and it’s certainly not an argument or presented or understood as evidence. It’s a backfilled fantasy for partisans who are willing to believe anything. Also, and perhaps mostly, it’s a tool of mockery for trolls, including the former president himself, who posts MAGA AI nonsense in the way he says and posts lots of obviously untrue things: to say, basically, “What are you gonna do about it?”

I don’t want to argue that nobody could possibly fall for something like this, and I’m sure there are at least a few people in the world who are walking around with the mistaken impression that Swift released a recruiting poster for the Trump-Vance campaign (I’m nearly as sure that these people have long known exactly who they are voting for). I also don’t want to argue that a correction-via-endorsement like this is mistaken or unnecessary. While these AI-generated images are better understood as implausible tossed-off lies than cunning deepfakes — more akin to Donald Trump saying “Taylor Swift fans, the beautiful Swifties, they come up to me all the time …” at a rally than to a disinformation operation — they’re still being used, in bad faith, to tell a story that isn’t true (and one that had the ultimate effect of raising the salience of a musician’s political endorsement that was almost inevitably going the other way). Consider the sort of fake celebrity porn that has proliferated online over the last decade: In many cases, these images aren’t creating the impression that public figures have had sex on camera, but are rather stealing their likenesses to create and distribute abusive, nonconsensual fantasies. This is no less severe of a problem than deepfakes as mis- or disinformation, but it is a problem of a slightly different kind.

As AI tools become more capable, and get used against more and more people, this distinction could disappear, and there are plenty of contexts in which deepfakes and voice cloning are already used for straightforward deception. For now, though, when it comes to bullshit generated by and about public figures, AI is less effective for tricking people than it is for humiliation, abuse, mockery, and fantastical wish fulfillment.

It’s good for telling the sorts of lies, now in the form of images and videos, that are stubbornly immune to correction because nobody thought they were strictly true in the first place. Swift’s post is typical of the popular AI backlash in that it’s both anticipatory — this stuff sure seems like it could go catastrophically wrong someday! — and reacting to something less severe that’s already happening — hey, this shit sucks, I wish it would stop! It’s a reasonable response to a half-baked technology that isn’t yet deceiving (or otherwise reshaping) the world at scale but in the meantime seems awfully well suited to use by liars and frauds. Her experience is aligned with that of the general public, for whom theories of mass automation by AI are still mostly abstract. For now, they just see the internet filling to the brim with AI slop.

There are echoes here of the debate over disinformation in the 2020 and especially 2016 elections, when the sheer visibility of galling nonsense on social media, combined with evidence that foreign governments were helping to distribute some of it, created the impression, or at least raised the possibility, that “fake news” could be swinging voters. It was an ill-defined problem that was distressing in the what-if-there’s-no-shared-reality sense but also sort of comforting in that it shrunk the more intractable problems of “lying” and “people believing whatever they want” into tech-product-size optimization and moderation issues. (Evidence that Facebook helped elect Trump is thin, but for liberals, Facebook’s obvious synergies with MAGA movement, and the dissemination of lots of literally unbelievable stuff, were certainly an indictment of the product and perhaps social media as a whole.) Trump’s hastily reposted fake Swifties, and Swift’s nuclear response, offer a glimpse of how, this time around, a new set of tools for generating and distributing bullshit might actually interact with popular politics: first as farce, then as brutal backlash.