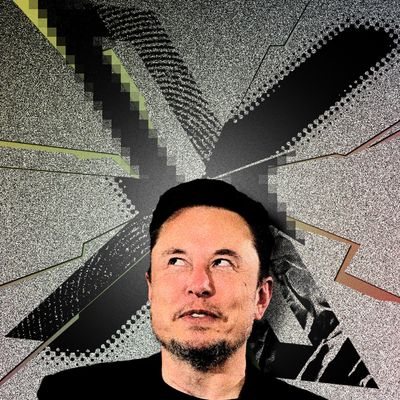

In October 2022, Elon Musk closed his purchase of Twitter, which he soon rebranded as X. Since then, things haven’t gone quite as smoothly as they might have. After bone-deep layoffs, the company is still bleeding talent. It’s valued at less than half of Musk’s purchase price. Prominent advertisers have fled. In response, Musk told them to go fuck themselves and decided to unban Alex Jones.

The owner of X posts like he’s on 4chan in 2016. The CEO of X posts like she’s on Facebook in 2012. From the outside, it’s tempting to conclude that X is a sinking ship, a cautionary tale about a company driven to ruin by one man’s inability to stop posting.

But on X, where Musk is the most popular user and where legions of supporters reply to his every post, the past year has been a spectacular success, and the coming years will only get better. Everything’s going to plan. Which plan, exactly? Let’s check in.

X will be the Everything App.

This is the original stated master plan, one of the take-Musk-at-his-word reasons for buying Twitter in the first place, and a recognizable goal with precedents in the real world: to turn X into something like WeChat, an app for multi-format communication, financial transactions, commerce, entertainment, and pretty much any other function currently assigned to the smartphone. It’s a big claim tantamount to Musk suggesting that his plan is simply to beat all other apps, to own the smartphone as a platform, and to take on the financial system. Less a plan, perhaps, than a goal — and less a goal, maybe, than an aspiration.

It turns out there’s a fine line between an Everything App and a Nothing App. On the one hand, despite various sorts of dysfunction on the platform and general distress within the company, X has, in the past year, shipped a bunch of new features. There’s a subscription tier and a limited revenue-sharing system. There are longer posts, longer videos, in-progress livestreaming features, and voice and video calls. There are fewer links, no headlines, and more Community Notes. There’s a job-listings feature, sort of. X is a licensed payment processor in a dozen states with more in process. There is evidence, in other words, that X’s significantly reduced workforce has been instructed to pursue various Everything App features and that those features are showing up in the product.

On the other hand, while many of these features are live, most of them are available only to subscribers to X’s paid subscription plan. Granted, if anyone wants to use X to do things other than posting and reading short messages, it’s the sort of people who are already paying $3, $8, or $16 a month to subscribe to it. But those people represent a minuscule fraction of X’s users.

For now, one might argue, users will subscribe once they hear of the wonders of the Everything App. Which, sure, but that’s sort of a different plan. The initial idea, which Musk has since repeated, is that Twitter would be an “accelerant” to creating a more powerful platform, a large network of people gathered and ready to receive his vision for the future. This is a reasonable-sounding idea. It’s also an idea that every other large social network has had, and tried to put into practice, and that has not really worked. From a much stronger market position, Meta attempted to turn its apps into an all-purpose platform with about a dozen different communications features, payments, commerce, content, and more. In practice, users have tended to pick and choose features that make sense on Facebook or Instagram or WhatsApp, remaining fragmented even within Meta’s own ecosystem. Google (like Meta) has long been a licensed money transmitter in lots of states and handles a range of transactions for users, but it’s far from most users’ “entire financial world.”

If you run a platform, having a lot of users is obviously valuable. But it’s also a liability. They came there for one thing, and convincing them to stay through slow change is hard enough. Twitter, which was for years a product defined by its constraints, cultivated an extremely stubborn and change-averse customer base. In practice, so far, those users have been less an accelerant than a decelerant, refusing to go along in sufficient numbers with any new plan and continuing to treat X like Twitter, posting and scrolling mainly out of habit (and for lack of a viable replacement). For his part, Musk doesn’t seem to mind driving them away and is seeking growth first and foremost among people in his fandom and ideological tribe in the form of paid subscribers. But again, that’s a different plan! That’s buying a social-media platform to basically destroy it and start from scratch, at extraordinary financial and reputational expense. Continued belief in that version of X, the Everything App, becomes at some point indistinguishable from a general belief in Musk himself, which is, to be fair, something a lot of people have.

X will be a key part of Musk’s AI masterplan.

This master plan is sort of new but easy enough to follow if you’re at all familiar with the superheated discourse around AI. Elon Musk is a big AI guy. He loves talking about how it might kill us but/and was also involved in founding OpenAI. Eventually, he parted ways with OpenAI, tried to take it over, failed, and moved on, except not really.

Around the time that Musk was trying to buy Twitter, then trying to get out of buying Twitter (don’t forget that part when entertaining the idea of any sort of “plan”), then actually buying Twitter, the only other thing the tech world could talk about was OpenAI. AI was not a core part of prepurchase discussions around Twitter and made only brief cameo appearances in the discourse about Twitter/X, mostly in the form of Musk complaining that OpenAI wasn’t paying enough for access to tweets, which it was using to train and otherwise augment its models. This was clearly about more than the money.

Fast-forward about a year and Musk has launched his own OpenAI competitor: the “based” and “anti-woke” xAI, which is financially tied to X in a sort of complicated way, mostly for fundraising purposes. This new entity hired a bunch of prominent AI researchers and engineers and released a chatbot called Grok, which talks like a trickster NPC in a fantasy MMORPG. Musk said Grok would be made available to the highest tier of X Premium subscribers

So the thinking goes something like this: OpenAI can try to scrape the web or buy access to data. Google, by virtue of being Google, has lots of material on which it can train and upon which its products can draw. But X, as a real-time feed full of current information, has something many competitors do not, which will make Grok more responsive to what’s happening in the world.

This, too, makes superficial sense, and Twitter’s data clearly had some value to OpenAI, which was paying a couple million dollars a year to access it. But like a lot of stories about AI, this relies on a whole bunch of stacked assumptions. Twitter is a giant corpus of a particular type, certainly. But is it especially good for training large language models at anything but writing tweets? As a resource for AI tools to call upon in real-time, does it have significant value not contained in the massive troves of text, much of it quite timely, produced by users at other companies with AI operations, like Meta or Google? Will any value that it does have flow back to X, which is being attached to Grok at the customer level as well?

In this scenario, X would be used by Grok more than the other way around as a source of training data and current content (a less generous way to describe such a relationship would be cannibalization). ChatGPT’s popularity didn’t depend on being integrated into a larger platform; a useful general-purpose chatbot speaks for itself and, if anything, can benefit from distance from some other determinative interface (consider using ChatGPT versus chatting with an OpenAI model in a Bing sidebar).

For argument’s sake, though, let’s imagine a fruitful relationship. If one value of X to an AI platform is providing it with proprietary real-time data — if it’s a way to connect Grok to up-to-date information about the world that other companies don’t have — then there are a couple of potential problems. One is that the content on X might be degrading. While plenty of people still post original, firsthand content on X, much of its newsy or usefully current material is aggregation or commentary. Musk has shown little reluctance in driving official news and information sources away from X and has suggested that he would prefer people publish directly on the platform, but like lots of things he wants for X, this isn’t really happening at a meaningful scale. Other changes to the platform — the algorithmic “For You” feed, the revenue-sharing features, the ideological lurch to the right among some of the most visible users and news-makers — have tainted the feed as a source of data that is about the world. (That’s not to mention pure volume: While X insists it’s doing fine, outside analysis suggests a steep drop in activity among users.) If we’re talking about understanding the universe, the content produced by X Blue Checks is maybe not where you want to start. As it stands, Grok and X are better positioned to feedback-loop themselves into reactionary oblivion. Or, if you trust the plan, reactionary … success?

X will defeat the “woke mind virus” and save civilization.

Speaking of which! Recently, a post from an obscure account containing the following statement came across Musk’s timeline: “I’m deeply disinterested in giving the tiniest shit now about western Jewish populations coming to the disturbing realization that those hordes of minorities that support flooding their country don’t exactly like them too much.” In response to this post, Musk wrote, “You have said the actual truth.” If you’re surprised to see Musk — you know, the Tesla guy — engaging casually with white-supremacist posts and virulent antisemitism, you shouldn’t be. Henry Ford got there first! Also, he has been doing this a lot! Musk’s X feed is clogged with approving replies to posts maligning immigrants, making fun of trans people, and insinuating that people he doesn’t like, or who don’t like him, are pedophiles. This is what he wants to share with the world, and though it gets a lot of attention — there’s a new controversy about his posts every week — it’s still shocking to read it all at once, not just for the ideologies on display but for the pure low-rent crank-ness of it all.

Recast as a crusade, this too has been touted as a plan of sorts — a reason for buying the platform — by Musk and others. Some supporters have extended the idea further:

Among other things, this is a questionable assessment of the role of X in reflecting and driving sentiment about Israel’s war with Hamas (far more sober and informed observers have tended to conclude that social media, including X, has instead helped foster or at least amplify sympathy and support for Palestinians under bombardment). It’s also a stretch in a more fundamental way. Twitter has always mattered a lot to Musk. Now, in some ways, it matters more to him and those who are aligned with him, now that it’s for them, about them, and identified with them. This has the secondary effect — a known problem with partisan social networks — of making it less important to everyone else and less influential to the world in general.

This plan has the distinction of succeeding, sort of, on its own terms within the walls of X. Musk unbanned tens of thousands of mostly right-wing accounts, let them buy check marks, and made very, very sure that nobody could ban him (last year, Musk upheld Alex Jones’ ban by suggesting that he was an extraordinary case and deserved “no mercy” as someone who had profited from the deaths of children). Now he posts whatever he wants, and his friends do, too. If Twitter was infected with the “woke-mind virus,” X has been cured of it through the administration of a hardy species of virus-eating right-wing brain worm. If you were convinced that pre-Musk Twitter was an engine of civilizational ruin, then you’re probably pretty satisfied with the past year. Unlike other master plans, you can declare this one achieved whenever you want:

The problem with — or the point of? — setting up civilizational stakes around the X product-feature roadmap is that things like “servicing debt” and “running a profitable company” don’t really enter into the equation. It’s certainly a way to change the subject! And while the broadest possible idea of a right-wing media company is neither unprecedented nor inherently hard to monetize, early moves in such a direction, including bringing Tucker Carlson’s show to the platform, are off to a wobbly start.

X will be a successful, normal social-media website.

In an interview with Andrew Ross Sorkin at the New York Times’ DealBook conference, Musk addressed allegations of antisemitism by effectively doubling down on the random X user’s assertion. This led the interview to an obvious topic: Is Musk worried about advertisers leaving? He responded:

To the extent there was a plan to grow or maintain X as a social-media platform — an attention aggregator supported by advertising — it was represented by the hiring of ex-NBC advertising honcho Linda Yaccarino as CEO. This was always a bit of a weird one. From the beginning, Musk emphasized that he wanted to shift to a subscription model for X, in part because Twitter’s ad business had never been especially impressive compared to its peers and because advertisers are sensitive to controversy. As a public company, however, Twitter’s ad business accounted for more than 90 percent of its revenue. In the beginning, it was possible, if already generous, to read Musk’s posts about the evils of woke-advertising as obscuring a more conservative plan to spin up a new subscription business while sustaining the company’s only real existing business. Classic mistake! Powerful men with posting habits should be assessed the other way around. The posts are the real deal; everything else is for show.

This is bad news for Yaccarino, the most comprehensively thwarted CEO in tech history, who has been reduced to posting stuff like this:

It’s also not ideal for Musk, who owes a lot of people a lot of money after overpaying for Twitter. Twitter’s draw for advertisers wasn’t its audience, which was smaller than the other social-media companies’, or its ad products, which were generally less effective than what you could buy from Meta or Google, but its concentration of influential people gathered together in a shared context. It wasn’t the greatest pitch, but it was a pitch — and it’s a pitch that’s becoming harder for Yaccarino to make as X becomes less appealing for anyone who isn’t really, really into Elon Musk. This would be less of a problem if the subscription business were showing signs of rapid growth, of course. It’s not.

X will finally make Elon Musk happy.

Taken together, the first year of changes at X looks incoherent. We’ve got an anti-advertising advertising business, a counterrevolutionary platform hidden behind a paywall, a product that is either food for AI or a platform for selling it, and an Everything App that’s also slowly turning into an app for replying to one guy and his friends. Its various successful theoretical futures seem incompatible and aren’t manifesting anyway. Not only are things not going to plan — it can seem as though there was never much of a plan at all.

Maybe not. But the past year of Twitter is coherent enough if you imagine it as an expression of one person’s desires, grievances, grudges, and worries. Twitter, now X, is a container for a bunch of stuff that bothers Musk. OpenAI is the one that got away. PayPal, which he once tried to rename X, is the other one that got away. As Musk’s profile and wealth grew, and as he felt he was accomplishing more, people praised him less and criticized him more; his superficial reputation as the “real-life Tony Stark,” the rocket guy, the Tesla zero-to-60-in-three-seconds guy — that one somehow got away too.

Years ago, a longtime SpaceX employee joked to me that the Boring project, Musk’s underground not-a-train company, was just a midlife crisis, an unwelcome minor distraction in an otherwise productive empire. It felt bounded — and sort of was. Digging holes under cities takes a huge amount of time and effort. It happens slowly, and even unrealistic projections were made in years. There was little gratification, and feedback was mixed. Impulsive leadership and wild demands at Tesla and SpaceX might run up against physical limits, worker safety, supply-chain issues, and regulation; eventually, someone at Tesla puts a windshield wiper on the Cybertruck. At the Boring Company, you hit bedrock.

Twitter was, in contrast, a software company with an advertising business, a social-media platform that was, by the standards of its peers, relatively slow to change but which could be changed immensely — and fast. X shrank the distance and time between vision and implementation and swapped high-dollar customers and contacts for users without influence or recourse, freeing up its owner to rapidly remake the platform in his own image. It’s a streaming site! A bank! A weapon in the war for free speech! We’re lifting the bans! We’re changing the logo to a doge meme!

This goes some way toward explaining Musk’s melodramatic attitude toward brands that don’t want to buy ads from him anymore. X was supposed to be free of such concerns, a virtual kingdom in which it would finally be possible to feel absolute executive authority. In reality, it exists at the mercy of two extremely capricious populations: risk-averse advertising executives at major consumer-facing corporations and fickle social-media users.

Anyway, this probably wasn’t quite a plan in the conscious sense, but we can still check in on it. Let’s ask the man himself:

Hmmm. Maybe that one was about something else. Let’s try again: