At one point in my life, not that long ago, during my tenure as a lawyer at a large New York firm, I spent my days trying to persuade judges that the word and really meant or.

In one particular case, billions of dollars turned on the distinction, which was at the center of a set of lawsuits that had been filed by lenders to the gaming company Caesars Entertainment, owner of Caesars Palace in Las Vegas and a bunch of other casinos. In early 2015, the company’s main operating subsidiary filed for bankruptcy, which set off sprawling legal maneuvers by the holders of roughly $18 billion in Caesars debt. Basically, they were looking to get their money back after the company was gutted. A key front in the court battle was a provision that relieved the parent company of liability if three specific conditions had occurred.

Two of the three had. In the contracts, the conditions were separated by the word and, so the bondholders argued that all three conditions had to occur in order for the parent company to skate free. The logic of the provision, however, suggested that the word and had been intended to be disjunctive rather than conjunctive — meaning that the occurrence of any one of the conditions (as opposed to all three) would suffice to terminate the guarantee. In other words, and really meant or.

The defense — that is, my side — was reasonably successful. In the end, the parent company avoided being held liable, bondholders took a modest hit, and the whole thing has been relegated to the annals of high-stakes corporate litigation — once closely followed by the financial press but now mostly forgotten.

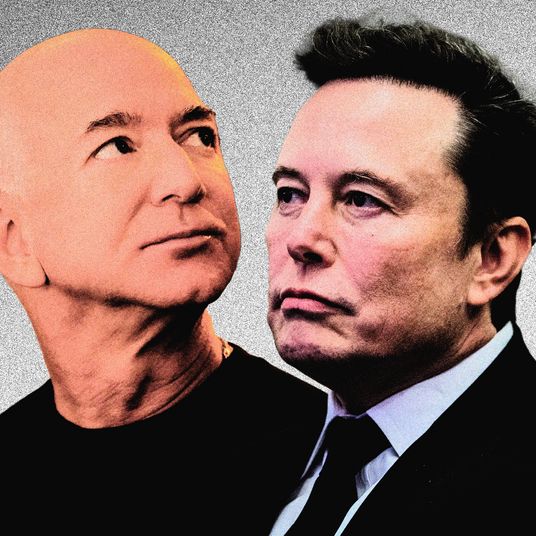

All of this is to say that I have a deep and hard-earned understanding of cases like Twitter v. Musk — seemingly ridiculous maneuvering in court battles between rich people and companies. This recent lawsuit, of course, was brought by Twitter over Elon Musk’s effort to withdraw from his agreement to buy the company. On Thursday, the court announced trial dates: the action will happen October 17–21 before a judge in Delaware. Late Friday, Musk filed a 164-page answer and countersuit that is currently under seal pending the resolution of redactions for sensitive, non-public information.

Whether we actually get a trial remains to be seen. On the surface, these major corporate cases tend to look like intractable conflicts headed toward a dramatic final verdict that will give one side total victory and the other total defeat. But from the inside, they tend to be subtle tactical battles where the only real stakes are slightly more or less favorable terms of an inevitable deal. Most major corporate cases settle before trial — the actual litigation functions as a sort of proxy drama over the eventual terms. If things are going well for your side in the early going, you adjust your settlement demands upward and vice versa. Billionaires and large public companies generally do not like uncertainty, and for that reason, they tend to avoid trials with huge amounts of money on the line, which can be the most uncertain of undertakings. (Of course, one question that looms over this particular proceeding is whether the world’s richest man might be playing by a different set of rules.)

We are still in the early stages of this jostling. So what are they both trying to achieve in their various maneuvers and legal gambits?

Twitter is likely to seek a ruling from the court that it is entitled to judgment as a matter of law based on the terms of the agreement with Musk. A decision like that would be a best-case scenario allowing the company to head off a trial that Musk has every incentive to make as protracted and embarrassing for the company as possible.

For Musk’s lawyers’ part, their principal job at the moment is to head off a quick ruling against their client, which means they need to create the appearance of as many legitimate and legally material factual disputes as possible — which likely helps to explain the absurd length of Musk’s response. They have claimed that, before a trial, they would need “at least 30–40 fact depositions, and at least 12 expert depositions in total” including “the principals and advisors that negotiated the merger, top management, board members, data science and audit personnel familiar with Twitter’s spam and false account detection procedures, finance and advertising executives, and executives knowledgeable about Twitter’s operational changes.” In its particulars, this position is absurd — cases of this complexity can be resolved by far fewer depositions and experts (if any) — but directionally, the argument is consistent with the strategy of someone who is on the defense in a case that has the potential to move very quickly and not in their favor. It’s not wrong to say that their top objective here is to plausibly find ways to waste everyone’s time. Twitter has claimed that the “uncertainty” caused by the Tesla billionaire’s efforts to get out of the deal adversely impacted the company’s most recent quarterly-earnings figures, so the longer this drags out, the better it ends up being for Musk and his efforts to wriggle out of a deal with a company that is not faring well at the moment.

There are two factors — even beyond Musk’s celebrity and Twitter’s familiarity — that amp up this dispute and make it much more interesting to observe than the average high-stakes corporate scrap. The first is Musk’s aforementioned wild-card psychology — it’s not at all clear that he will do the things that 99 percent of participants in cases like this do. The second is Twitter’s peculiar bind. There has been much talk in the press about how awful the public fight with Musk has been for Twitter’s business, but even if that is true, this does not mean that Twitter should — or even can — try to settle the case as quickly as possible. For better or worse, the company’s legal claim against Musk may now be its single most valuable asset, and the board has a fiduciary duty to its shareholders to maximize the value of that claim, even if that ultimately means trying to force Musk to go through with a deal to buy a company that he may no longer want and that he has thoroughly trashed since agreeing to buy it.

What follows is an overview of the landscape of this case based on my time in the corporate-litigation game.

.

The Lawyers

The two sides are nicely lawyered up for this fight. Twitter is represented by Wachtell Lipton, which is famous for maintaining just one office, in midtown Manhattan, and for overworking its junior lawyers (even by the standards of large New York firms), which is why it may be the most profitable firm in the country. Simpson Thacher represented Twitter in its deal negotiations with Musk and continues to represent the company’s board. The firm once had a (dubious) reputation for being a slightly kinder and gentler workplace amid the general hellscape of life at big firms in the city.

Musk is represented by Skadden, another highly profitable member of the New York–based Big Law elite, as well as Quinn Emanuel, which has represented Musk in the past and has a reputation for being particularly mercenary and aggressive — at least by the standards of bloodless white-collar lawyering. The lead Quinn Emanuel lawyer representing Musk once found himself in hot water after speaking with victims of Harvey Weinstein about representing them while he was in the process of leaving the law firm that was working for Weinstein himself. (I once litigated against him when I was still a prosecutor — a perfectly amiable affair that ended rather awkwardly for the firm.)

Expensive lawyers with impressive pedigrees in a high-profile legal battle can seem gladiatorial and intimidating. The reality tends to be a lot less glamorous. Most of the pretrial work will take the form of youngish, paunchy lawyers no one has ever heard of drafting things at their desks until late in the night (briefs, discovery requests, deposition outlines, a 164-page answer/countersuit, and the like) with the older, lead lawyers providing strategic direction and the final changes to all of those documents. It used to be that these legal foot soldiers — the associates and junior partners — at least had to get dressed up and go to the office to do this, but plenty of them are still working in their pajamas much of the time.

No one on the outside can say for sure how much all of these lawyers will cost, but one estimate puts it at “a potential eight-figure legal bill” for each side divided among the legal teams. That sounds about right, and it sounds like a lot, but it is a drop in the bucket for these firms. Skadden’s revenue last year alone exceeded $3 billion.

The reason is not simply that these firms do a lot of work for a lot of different clients, but also because the most lucrative white-collar litigation work involves representing companies in protracted, years-long lawsuits and investigations (of both the internal and governmental variety) — ideally with no real time constraints. These are the sorts of undertakings that involve lots of documents, lots of witnesses, lots of obscure and debatable legal issues and procedures — and, in turn, lots of billable hours at rates that can now reach upward of $2,000 per hour for the most experienced lawyers and around $1,000 per hour for even relatively junior ones.

.

The Details of the Case

Twitter v. Musk does not have the hallmarks of one of these cash-cow disputes — to put it mildly. After Twitter filed its lawsuit against Musk, most legal observers quickly concluded, with good reason, that Twitter is on much stronger legal footing than Musk is. (One expert I spoke with before Musk’s filing on Friday, who asked not to be quoted by name, went so far as to say that Skadden “should be feeling a little embarrassed” about the weakness of Musk’s defense.)

Twitter filed its lawsuit in the Delaware Court of Chancery, which specializes in arcane corporate litigation, but the case is a conceptually simple one: a single breach-of-contract claim premised on Musk’s effort to terminate the merger agreement that the two sides executed back in April. Twitter sought an expedited pretrial schedule over Musk’s objection, so when the presiding judge first ruled that she would set aside five days for a trial in October, it was an early win for Twitter.

At the time of the agreement, Musk agreed to pay $54.20 per share — a 38 percent premium over where the stock was trading at the time. After the parties signed the deal, however, the market continued its year-to-date slide, Tesla’s stock price took a huge hit, and Musk’s wealth, along with that of the rest of the billionaire boys’ club, shrunk significantly. Meanwhile, Musk loudly claimed that Twitter may have misled regulators and the public about the number of bots on the platform, which, the company has consistently said in public filings, represents less than 5 percent of the company’s monetizable daily active users (“mDAU” for short).

As many observers have noted by now, this all seems to have been quite backward. Musk’s deal with Twitter had no due-diligence condition, so when he executed the merger agreement, he effectively signed away his ability to quibble with the company over its financial condition and operations. Musk nevertheless claims that Twitter’s possible misrepresentations about bots might amount to a “material adverse effect” on the business, which, under the terms of the merger agreement, would allow Musk to get out of the deal.

Delaware courts have proven extraordinarily reluctant to make such a finding. “There’s been exactly one in the history of Delaware,” noted Ann M. Lipton, a law professor at Tulane who studies corporate governance and once worked as a securities and corporate litigator. “It was big headline news,” she explained, but “the differences between that case and this one are quite stark.” In that case, which involved the acquisition of a drug manufacturer, there was “not only a dramatic drop in revenues” on the part of the acquisition target, but “the company turned out to be dramatically and horrifically out of compliance with FDA requirements.” Here, Musk has thus far offered no real evidence that Twitter’s figure, based on its proprietary metrics, is actually wrong — much less so wrong that the truth would effectively destroy the company’s business prospects.

Musk has claimed that Twitter violated an “information covenant” in the merger agreement, which required Twitter to “furnish promptly … all information concerning the business, properties and personnel of” Twitter “for any reasonable business purpose related to the consummation” of the deal. Morgan Ricks, a law professor at Vanderbilt who once worked as a mergers and acquisitions lawyer at Wachtell and conducted merger arbitrage for the hedge fund Citadel, took a similarly dim view of this argument, telling me that Musk was apparently “trying to do a proctology exam on the company, and that’s not what an information covenant in an M&A deal is about. It’s not a way to do diligence. It’s a way to get the deal done.”

Finally, Musk has claimed that Twitter violated the “ordinary course” covenant in the deal, which required Twitter to use “its commercially reasonable efforts” to conduct its operations “in the ordinary course of business.” Musk has complained about a handful of Twitter’s recent personnel decisions, but the phrase “commercially reasonable efforts” is notoriously loose and company-friendly, so Musk is likely to face an uphill battle on this front too.

For the moment, the details of what is in Musk’s countersuit from Friday are unclear, but the length and quality of a legal filing are often inversely correlated, and again, Musk’s overriding strategic objective is to make this litigation as unwieldy and convoluted as possible even if he ultimately has little to work with. After the filing, the Wall Street Journal reported based on discussions with “people familiar with the matter” that one of Musk’s counterclaims “is expected to center on the allegation that Twitter changed its number of monetizable daily active users shortly after agreeing to the deal, and then didn’t provide thorough responses to request by Mr. Musk’s team for data on the spam number” — an assertion that suggests the unsurprising possibility that Musk has converted some of his legal defenses (that Twitter violated its obligations under the merger agreement) into affirmative, mirrored legal claims of his own. To the extent that is what Musk’s lawyers have done, it will not necessarily make the arguments any better.

It is also not clear that Musk’s latest salvo will slow things down at all. The filing was made pursuant to a scheduling order that contemplated the filing as part of a broader case management plan and that gives Twitter until the end of the day on August 4 to file a response.

.

How Will It All Play Out?

If you were to strip out the identities of the parties in this little fact pattern — the Twitter and Musk of it all — this would not be a particularly attractive or suspenseful dispute except, perhaps, for corporate litigators and academics whose jobs are to follow minute developments in Delaware court interpretations of M&A law. The legal issues are perhaps novel but not terribly interesting, and the most salient factual dispute, concerning Twitter’s measurement of bots on the platform, is likely to be a technical morass if it really needs to be fully explored.

In the ordinary course, it is not even clear that a court would allow the case to go to trial, since a judge could conclude that Musk’s factual claims — the questions about the bots, the complaints about the information that Musk received from the company, the gripes about the personnel decisions — are legally insufficient to terminate the deal under the language of the contract — even assuming that his assertions are correct.

“I’m not convinced the case needs discovery,” Lipton told me. “He hasn’t even made a good case that he actually needs the spam information.”

Ricks noted that the presiding judge would likely feel some pressure to “give both parties a fair hearing” at trial — including by allowing each side “to put on the stand people who are involved in the deal just to get to the bottom of what was meant by particular contractual terms and what actually happens in the supply of information after the deal was signed and everything. I personally think it’s really unlikely that there’s not a trial” — assuming that there is not a settlement.

Twitter’s lawsuit seeks “specific performance” of the agreement, which would mean a court order that Musk has to go through with the deal at the price set forth in the merger agreement. Rulings like this in Delaware have historically been very rare, but as it happens, the judge presiding over Twitter’s lawsuit issued one of the few rulings like this in a case last year — another bad sign for Musk’s litigation prospects. The court might also rule against Musk but conclude that the company is only entitled to the $1 billion termination fee provided by the contract — a figure that, at least with the benefit of hindsight, was far too low. (One very rough and unscientific way of understanding the gross inadequacy of the fee is that the delta between the company’s current market cap and the $44 billion valuation reflected in the Musk deal is more than $10 billion.)

Of course, an out-of-court resolution remains very possible — perhaps even likely. Conceptually, a settlement in which Musk agrees to pay a higher termination fee or Twitter agrees to accept a price lower than $54.20 per share are both possible. This does not necessarily need to happen before the presiding judge rules — even after a trial. A ruling on the merits of the case, one way or another, would shift the parties’ negotiating leverage, and they would be free to settle the case afterward using the court’s ruling as a lodestar.

Many industry observers have noted that Twitter will want to resolve this mess some way or another sooner rather than later, since Musk has proven to be an extraordinary nuisance to the company and its shareholders, the company’s board, and its employees, but that operational imperative will have to be balanced against the board’s legal obligations given the hand they currently hold. As a matter of law, the board is basically obligated to its shareholders to wring as much money out of Musk as possible.

As for whether it is realistic to expect Musk to follow a court order that requires him to complete the deal, I think the concerns in some quarters that he would refuse to comply are slightly overblown. Even terrible people usually comply with court orders after exhausting their options. Samuel L. Bray, a professor at Notre Dame Law School who specializes in the law of legal remedies, told me over email that the court “would have a wide array of means to enforce its decision … The tools that the Court would have in its toolbox to ensure that compliance are varied. They include fines (so many dollars per day), the loss of certain legal arguments, seizure of property, imprisonment, and litigation costs and attorneys’ fees,” though Bray stressed that “courts would not use imprisonment unless they had to, and would be more likely to rely on fines and similar measures.”

Lipton noted other, more practical obstacles to noncompliance on the part of Musk, particularly since Tesla is incorporated in Delaware. “I do not believe that he can function as the head of a Delaware public company, which constantly has business in Delaware, and continue to do that while antagonizing the Delaware courts,” she told me. She noted that Skadden’s lawyers are “always before the Delaware courts,” so a major client defying a court order would be a problem for them too (though clients sometimes do not care about such things). “I don’t think he’s going to defy a court order after, of course, he exhausts appeals,” she concluded.

For now, Musk’s situation is less a problem for him than for his lawyers, who have to be well aware that this is someone who does not actually respect them much — if at all. Lawyers are sometimes paid handsomely to debase themselves in the service of their well-heeled clients, and this may ultimately prove to be one of those situations, but it is still early in the going, and, in any case, no one should feel bad for anyone involved. Twitter may be highly influential among the media and political classes, but it also might be a terrible, socially destructive force that deserves to die a natural death. Musk’s litigation position looks pretty poor at the moment, but he has plenty of money to lose and appears to be largely indifferent to the public and media perceptions of him and his antics. On some level, the two sides deserve each other.

Meanwhile, like other recent high-profile legal fights, this may prove to be a largely guiltless indulgence for those of us following along from home. Settle in, and enjoy it while it lasts.