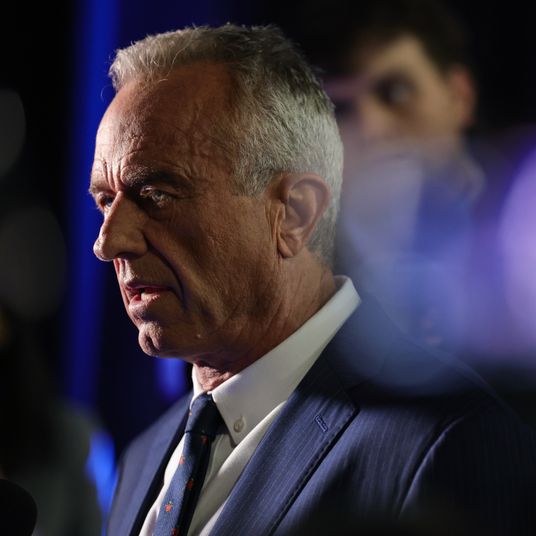

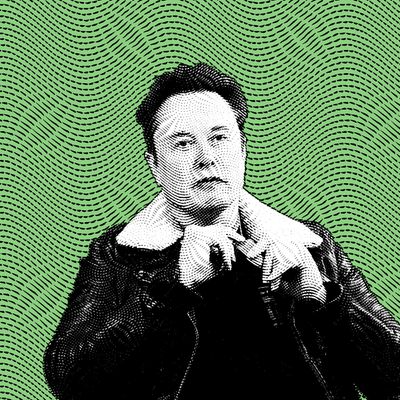

There was nothing inevitable about the electric-vehicle market Elon Musk built around his flagship company, Tesla. The development of rechargeable-battery technology, the techy design reminiscent of Apple, the cheap cost of lithium and other metals, the successful save-the-planet marketing — with some combination of luck, skill, and good timing, Musk put all these elements together in a combination that was, when Tesla was still a fledgling company, novel for the auto industry. It made him the world’s richest man and most influential connoisseur of weed jokes. Tesla became worth more than its five biggest rivals combined and the world’s top seller of electric vehicles. Even last year, when competition was at its most fierce, he still commanded half the U.S. market for EVs.

Could the Musk Empire be crumbling, though?

On Tuesday, Tesla reported it had delivered 386,000 vehicles in the first three months of this year, a 15 percent drop from what Wall Street had been expecting just a few weeks ago and the first annual drop since 2020. It is not the end of Tesla — not even close. But the decline is the latest signal that the U.S. market for electric vehicles is facing a historically bad year, and it points to a more acute problem for Tesla’s dominance over the market it all but created. With fiercer-than-ever competition for customer dollars alongside higher manufacturing costs, the brief window in which Musk could do no wrong for Wall Street is over.

Tesla is past its peak — at least as far as its stock is concerned. The company’s share price reached its all-time high of $409.97 on November 4, 2021, and has since fallen about 60 percent to $164.42 on Tuesday after the delivery numbers were released. This ultimately represents a decline in Wall Street’s confidence in Musk. And it’s easy to understand why: This was the worst drop in Tesla’s history by a fair margin. While analysts were expecting a small drop — from 457,000 deliveries to about 420,000, a magic number in Muskland — even some of Musk’s most outspoken supporters have balked, with analyst Dan Ives calling the sales figures an “unmitigated disaster.”

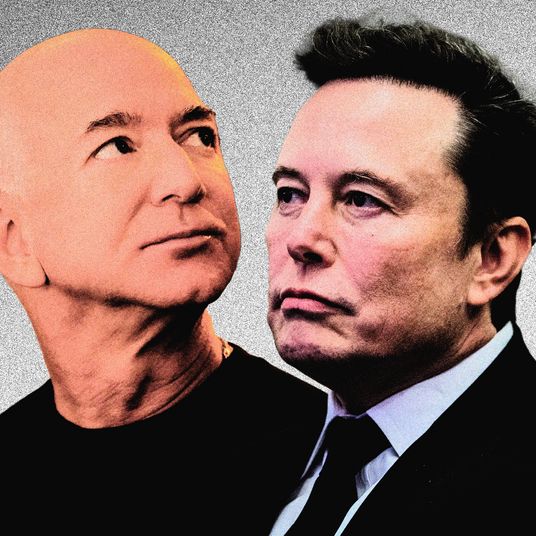

Since the company hit its 2021 peak, Musk has embarked on a few major blunders that have made investing in his company a much riskier proposition. There was, first, his takeover of Twitter — a deal funded in significant part on the back of Tesla’s monster valuation and weighed down by the company’s stock price. (At its peak, it was worth more than $1 trillion, putting it among a small group, including Apple, Amazon, and Meta, that have breached that mark). More recently, there was the long-delayed rollout of the Cybertruck, Musk’s $100,000 or so SUV for Buckminster Fuller superfans — not a huge market. (On Tuesday, Tesla didn’t even break out its sales of the truck and instead opted to lump in its most recent model with its older, unpopular S and X cars — a category of lesser Teslas purchased by a mere 17,000 customers.)

And then there’s the competition. In the U.S., the ranks of electric and hybrid cars from Kia, Rivian, and General Motors have fundamentally changed the market. No longer are EV buyers synonymous with Musk superfans — a reality that has been especially challenging for Tesla. But globally, the biggest threat is the Chinese carmaker BYD, which sold about 300,000 vehicles last year, up about 13 percent from the previous year, and was briefly the world’s biggest seller of EVs thanks to China’s status as the world’s biggest market. Tesla, which was selling more than half its cars in China, needs to keep growing there to retain its world title.

The silver lining in Tuesday’s report is that Tesla did sell enough during the first quarter to regain its title as top EV-maker in the world, but Musk himself has warned that, in the long term, China “will pretty much demolish most other car companies in the world,” and he called for trade barriers to stop them. (Luca de Meo, the CEO of Renault Group, has also warned against BYD’s dominance and called for Europe-wide industry cooperation, saying “the prosperity of Europe is at stake.”)

Still, shifting geopolitics has made Musk’s inroads there smaller. The Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act has been discontinuing its subsidies of EVs that contain metals mined from other countries, making the number of Teslas eligible for a federal tax credit far smaller than just a few years ago. (Two of the largest future sources of lithium in the U.S., crucial for rechargeable batteries, are now controlled by GM and ExxonMobil, which puts Tesla at a competitive disadvantage as prices start to come down.) High interest rates have also made it harder for customers to buy the cars. Meanwhile, why would China support a naturalized American billionaire over its own homegrown industry?

There have been other issues for Tesla — disruptions in the supply chain via the Red Sea, an arson attack on a German plant, the federal investigation into its “full self-driving” mode. But these pale in comparison to Tesla’s losing market share. Teslas are now cheaper than ever, but anyone in the market for a car today is less likely to buy one of Musk’s than they were last year. Of course, he has found ways to turn things around before. Given his long and varied mastery of the tech industry, not to mention his inexhaustible wealth, Musk is arguably unparalleled in his ability to bounce back from this low. But it may take more than the sheer force of his will to do it.